Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley & Livingstone (27 page)

Read Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley & Livingstone Online

Authors: Martin Dugard

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Explorers, #Africa

26 MAY 1871

Gondokoro, the Upper Nile

730 miles from Livingstone

STANDING ON THE

edge of the Nile, rows and rows of polished soldiers standing to attention on his new parade ground, Sir Samuel White Baker had every reason to be proud. It had taken him nearly a year and a half, but he had successfully travelled almost the entire length of the Nile and established a British presence in Gondokoro. His position was four degrees north of the equator. Ujiji, by coincidence, was four degrees south.

The winds were light and variable, and the temperature was nearly eighty degrees. As local Bari tribesmen looked on from a distance, naked and curious about the squat bearded man speaking so gravely, Baker pronounced to all assembled that the new outpost was now a colony. Its name was Equatoria. He was now poised to solicit any and all information about Livingstone’s whereabouts.

There had been times on the long journey upriver when Baker doubted he would ever reach Gondokoro. The Sudd, for instance, nearly broke him. Located five hundred miles south of Khartoum, the swampy section of the Nile was

the most confounding stretch of river on earth. Papyrus ferns and the detritus swept downriver from Lake Victoria clogged the Nile’s flow in the Sudd, so effectively bringing it to a standstill that the river stagnated. The banks, which were almost impossible to discern from the choked river, were nothing but unstable mud and impenetrable jungle for a hundred miles in either direction. Crocodiles and hippos loitered in the stinking miasma. Snakes moved without a sound through the reeds and trees. The sun hovered glowing and hot, like the tip of a lit cigar. The Sudd was not land, and not river, and Baker’s expedition had been stuck for weeks.

A smaller expedition could have found an alternative route, perhaps hacking through the undergrowth alongside the river. Baker, however, was driving an army. Under his command were 1,700 Sudanese and Egyptian soldiers. Forty-eight sharpshooters protected his and Florence’s every movement. He had a personal assistant, a doctor, two engineers, a shopkeeper, an interpreter and a shipwright to consult in times of indecision. He also had an entire fleet. It had taken fifty-five sailboats and nine steamers to transport Baker’s men the 1,500 miles from Cairo to Khartoum. The largest steamboat was a hundred feet long and weighed over 250 tons.

Baker, his wife, his assistants, his army and his armada lit the boilers in Khartoum on 8 February 1870. Their intent was to travel through the Sudd, then five hundred miles beyond it to the abandoned Austrian mission station at Gondokoro. There they would claim the land, establish a military presence and explore. Finding Livingstone, as Baker promised Murchison, would be a primary objective.

Baker was no stranger to adversity or exotic conditions. Before becoming an explorer he had spent 1859 to 1860 supervising the construction of a railway between the River Danube and the Black Sea. He had gone to Africa in 1861 to hunt big game. Searching for the Source was just a sideline. Travelling with Florence, a blonde Hungarian dynamo fifteen years his junior who would later become his second wife, Baker had worked his way upriver from

Cairo on an earlier Nile expedition. He crossed paths with Speke and Grant in Gondokoro in March 1863. Though disappointed to hear that Speke had hypothetically confirmed Lake Victoria as the Source, Baker and Florence pushed on in the hope of discoveries of their own. On 14 March 1864 the pair discovered a lake just north of Victoria. Appropriately, they named it Albert, for the Queen’s late husband.

Queen Victoria, however, was chagrined to learn that Baker and Florence were unmarried. And, worse, that the Hungarian was a Catholic. Though Florence converted to Anglicanism upon their return to England and the Bakers became husband and wife shortly after, the bohemian tone of their trek to Lake Albert was in stark contrast to the spiritual glow in which, for the British public, Livingstone’s journeys were imbued.

It was Baker, however, who had the most compassion for Livingstone’s plight and who had quickly taken up his pen to write to Murchison on 8 March 1867 when reports of Livingstone’s murder surfaced. ‘I would rather die thus’, he wrote of sudden death by the Mazitu, ‘than be slowly poisoned by a doctor; and the hard soil of Africa is a more fitting couch for the last gasp of an African explorer than the down pillow of civilized home. Livingstone’s fate seems to have cast a gloom over African travels, and the papers appear to taunt African travellers with running quixotic risks. If England is becoming so cowardly and so soft that travel shall cease in dangerous countries because some fall victim to it, then it is time to roll up the English flag and admit the decline of the English spirit. In all humility,’ he concluded, offering his services as an explorer to Murchison once again, ‘I am ready.’

Baker’s straightforward letter was a showcase of his complexity. In his renaissance-man lifetime, Baker had founded an agricultural community in Ceylon, shot tigers in India, hunted bears in Russia and undertaken his first Nile exploration just for the thrill of seeing somewhere new. Once, when an African king who was holding the

Bakers hostage suggested he and the rugged Englishman exchange wives, Baker boldly pressed a revolver into the king’s stomach and told him exactly how little he thought of the idea. For good measure, Florence then charged forward and berated the king in Hungarian.

The Sudd, however, was to prove a year-long obstacle in 1870–71. Hundreds of men died in the back-breaking, futile attempt to clear a channel. So when Baker finally got men and material through the quagmire by building an impromptu dam that raised the water level high enough for his ships to float through, he was mightily relieved.

The celebration was saved for Gondokoro. On 26 May 1871, just five days after Stanley marched from Mpapwa, Baker ordered his remaining twelve hundred soldiers to assemble in clean uniforms. The tiny settlement lay on a hill overlooking the Nile. Lake Tanganyika — and, more important, Ujiji — was just a few hundred miles south. The ruined red-brick Austrian mission huts and sheds had been repaired. A fort consisting of three main buildings and a living area of African-style conical-roofed mud and stick huts were built adjacent. A fence surrounded the settlement, starting at the Nile and running inland around the complex. Vegetable gardens were planted. Baker’s vessels were docked along the shore, parallel to the bank, except for the biggest steamship, which was moored nose first into a small inlet. Baker, showing he hadn’t forgotten his roots as an engineer, even concocted a still.

That balmy May evening, the Bakers dined on roast beef, Christmas pudding and rum. The celebration was an acknowledgement that their goals were being accomplished one by one — slowly, but accomplished nonetheless. Baker was the premier British presence in the interior. He was the new tip of the African spear, hoping to build commerce in the interior and stamp out slavery. He was also poised to go in any direction to find Livingstone, and had already begun the habit of interviewing any and all passing travellers for signs of the elusive explorer.

Unknowingly, that night Sir Samuel White Baker and his lovely wife Florence were almost exactly the same distance from Ujiji as Stanley.

TEN HUMAN JAWBONES

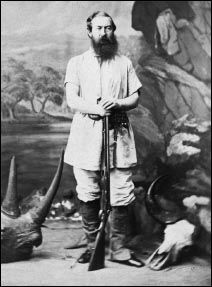

Sir Samuel White Baker

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

24 MAY 1871

Nyangwe

AS LIVINGSTONE ENJOYED

the splendour of life in Nyangwe, he developed a favourite pastime: visiting the village market. Thousands upon thousands of Africans came from surrounding villages to take part. Most were women, though he did observe the comings and goings of the local men, all of whom considered themselves to be chiefs. Livingstone, then, enjoyed the marketplace from both an anthropological and a masculine point of view. ‘With market women it seems to be a pleasure of life to haggle and joke, and laugh and cheat: many come eagerly and retire with care worn faces; many are beautiful and many old; all carry very heavy loads of dried cassava and earthen pots, which they dispose of very cheaply for palm oil, fish, salt, pepper and relishes for their food.’

Day after day, waiting for the people to trust him enough to rent him a simple canoe, Livingstone observed the comings and goings of the market. Ultimately, in a way he could only foresee if he shrugged off the trusting nature that allowed him to travel through Africa unscathed,

his marketplace observations would come between him and the Source.

The 24 May 1871 entry in Livingstone’s journal was yet another marketplace observation. He was still too feeble to walk any sustained distance, and the rainy season made travel difficult. He was also still without a canoe. ‘The market is a busy scene — everyone is dead earnest — little time is lost in friendly greetings,’ Livingstone wrote. ‘Each is intensely eager to barter food for relishes, and makes strong assertions as to the goodness or badness of everything. The sweat stands in beads on their faces. Cocks crow briskly even when slung over the heads hanging down. Pigs squeal.’

Though the only white man for hundreds of miles in any direction, the people had finally got used to Livingstone’s presence. He had been able to sit undisturbed, or, when the opportunity arose, make the occasional bit of conversation. On 27 May 1871, Livingstone remarked in his journal, ‘A stranger in the market had ten human under-jawbones hung by a string over his shoulder. On inquiry he professed to have killed and eaten the owners and showed with his knife how he cut up his victims. When I expressed disgust, he and others laughed.’

Livingstone, however, had little to fear from the cannibals of Manyuema. Their parameters for eating human beings were narrow: opponents conquered in battle, and fellow tribesmen killed by disease. The bodies were not cooked before eating, but soaked in running water for several days until bloated and tender. Male flesh was considered preferable to that of female, so women were consumed only when no other food was available. As a result of their cannibalistic tendencies, and also from a tendency to consume animal carrion, the people of Manyuema had a powerful body odour. The Nyangwe marketplace, as a result, with thousands of Manyuemans crowded together, carried a strong aroma.

Livingstone was not an enemy, nor was he a fellow tribesman, so he would not be set upon and made a meal of. The cannibals, then, posed no threat to his being. As a

result, he passed his days in the bustling village, waiting for the chance to rent a canoe and continue his journey downriver. It was an idyllic time, marked by prolonged periods of marketplace observation and journal entries about the beautiful women of Nyangwe. Livingstone assumed that neither he, nor the people of Nyangwe, were in any danger.

He was wrong.

31 MAY 1871

The Marenga Mkali

600 miles from Livingstone

IN EAST AFRICA,

along the trade route between Bagamoyo and Ujiji, the portal between the coastal lowlands and the high-altitude grasslands of inner Africa — in essence, the entrance to Africa’s beating heart — was a barren strip of hell known as the Marenga Mkali. Thirty miles wide, defined by heat, dust and an utter lack of water, it advertised to one and all that journeying into Africa was not going to get any easier. Temperatures reached 120 degrees at midday. White ants, red ants and scorpions made each night’s camp a festival of irritation. The smallest insects worked their way into food, bedrolls, clothing and ears. A scalding wind blew across the land, too, forcing sand into eyes and noses. ‘Not one drop of water’, Stanley wrote, ‘was to be found.’