Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes (22 page)

Read Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes Online

Authors: Kamal Al-Solaylee

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Middle East, #General

At the immigration booth my worst fears were confirmed. I was flying on my Canadian passport, which clearly stated Aden as my place of birth. According to a staffer at the Yemeni embassy in Ottawa, I didn’t need a visa if my passport spelled that out. The officer checking my passport at Sana’a International Airport hemmed and hawed about the fact that I should have applied for a visa. Although I didn’t believe a word of it, I protested that this was my homeland and I had the right to visit my family whenever I wanted. The usual barrage of questions followed. Where did my family live? I honestly wasn’t sure, as houses in Sana’a didn’t always have street numbers. It was somewhere on the Ring Road in the Hasaba district, I replied. When did I last see them? About eight years before. Why so long?

That I couldn’t answer in a sentence or two. Eventually, he let me in, but asked that I register with local security as an alien. Finally we were in agreement on something. At Customs, the security guard asked why I had brought so much chocolate with me all the way from Canada. It was the only request from my sisters for their children. Most of the chocolate sold in local stores tasted stale or was too expensive to be a daily treat.

Khairy waited for me at the arrivals gate. The drive home took longer than usual. Traffic had something to do with it. Even more cars, more people. We didn’t pass an intersection without a filthy-looking child or an older bedraggled woman begging for money. “Displaced Iraqis,” my brother explained, in case I thought they were native Yemenis. Then he broke it to me. “I want you to be prepared when we get home. Things have got a bit difficult for the family.” That sickness in my stomach returned instantly. I asked him to elaborate. “You’ll see.” His tone was that of an older brother providing counsel, but it contained hints of a resentment that the passage of time had not eased. After all, I was the one who’d selfishly thought I deserved better than the rest of my family and had chosen a different life for myself. I’d also refused to visit them for so many years, despite several invitations. They took it personally, and I didn’t blame them.

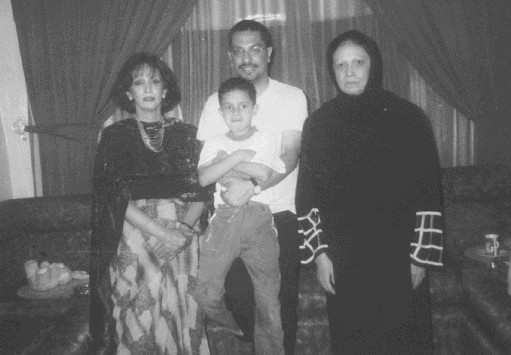

Posing with my closest sisters, Ferial (right) and Hoda, while holding my nephew Motaz in Sana’a in 2001. It was the last time I saw Ferial, who died a year later from a brain aneurism.

The changes Khairy had tried to prepare me for were easy to spot. It was more than simply the passage of time. Two of my sisters—Hoda and Ferial—were thin to the point of looking sick and anemic. Hoda was only forty-six but was missing half her teeth and using dentures. Ferial, fifty, had lost her job at the USAID after the USS

Cole

incident and suffered a deep and long depression, in a country that barely recognized mental health issues or knew how to deal with them. The idea of therapy would sit alongside Botox or liposuction as an example of Western vanity and decadence, even though our father relied on counselling in the 1970s to get over his losses. Raja’a, forty-two, had gone from wearing the hijab to a full-scale niqab, where only her eyes were visible. She said she preferred the anonymity it gave her. Still working as a librarian at Sana’a University, she occasionally got stopped by students in the market if she wasn’t wearing the niqab, just for a chat or to ask library-related questions. She said the niqab made her feel more mobile, free to move from one store to the next. I didn’t think that was a good excuse, but wearing it was not just camouflage to her. It felt right, she said.

As for my mother, I hid a sigh when I saw her hunched walk and wrinkled face. She could only get from her room to the bathroom or kitchen by holding on to the walls for support. My sisters would take turns ensuring that the bathroom floor was dry, as a slip could be fatal. She was just seventy. Years of inadequate medical care, intense political and social pressures after the civil war ended in 1994 and various family arguments after my father’s death had taken a toll on everyone. But my mother seemed to have borne the brunt of it.

The men hadn’t fared much better. As Helmi told me, raising a family in Sana’a was a daily challenge. Public schools are underfunded, there were no playgrounds for children to be children—and God forbid any one of them got seriously sick. You took your life in your hands every time you went to a hospital in Sana’a. “You’ve escaped all this,” he said. I answered with a simple “Can you blame me?” While deep down I didn’t think they really did, there seemed to be a collective will to punish me for abandoning them. At least Faiza had returned home when her life in England came to what the family might call a natural end. When I showed them copies of

Elle Canada

magazine and a few of my

Eye Weekly

and

Globe

stories, they seemed less impressed and more concerned with the fact that someone with a Ph.D. in English made a living out of writing for newspapers and magazines. It seemed so beneath my education, and in a field not worthy of a Muslim’s attention. If they asked me any questions at all about my career choices, they tended to focus on how I made money or spent it.

It seemed we needed an interpreter—someone who could explain to them how my life had panned out in Canada and, in turn, tell me how theirs had unfolded against Yemen’s many crises. I understood the words they were saying, but my mind couldn’t piece together their meanings. It wasn’t very long before I started counting the hours until bedtime so I could get relief from our struggle to comprehend one another.

But it was the level of religiosity that truly startled me. My sisters were checking in on each other to make sure they prayed. When the TV was not tuned to Egyptian or Lebanese soap operas, it was on networks as diverse as Al Jazeera and Al-Manar, the latter the PR wing of Hezbollah. It was on one of Al-Manar’s programs that I encountered the name Osama bin Laden for the first time. I don’t think I had heard of him before. He was presented not as a threat but as one of the forces that were keeping the West worried about the return to Islam. I made no note of it. Just another radical jihadist from Saudi Arabia’s elite—a spoiled rich kid who needed a cause to latch on to.

In the past, we’d all watched Hollywood movies or TV shows as a family, but now, despite all the TV watching, there seemed to be very little room for curiosity about the Western world. We’d grown up on episodes of

The Rockford Files, Columbo

and

The Bionic Woman

on the American side, and

Upstairs Downstairs

on the British. Classic Hollywood movies from the 1940s and ‘50s were essential viewing.

Now, Voyager

, starring Bette Davis, had become a firm favourite for me and my sisters. Ferial loved Humphrey Bogart; I, Claudette Colbert.

I did notice that my nieces had a passing interest in episodes of

Friends

, which some Gulf TV station showed with Arabic subtitles. I don’t know if they ever saw the episode where Chandler pretends to be going to Yemen to escape the annoying and persistent girlfriend Janice. Joey, the Italian jock in the show, congratulates Chandler on choosing a name that sounds like a real country.

Attempts to engage my sisters in old stories about life in Cairo or Beirut were successful, but would be followed with remarks like, “Those days are long gone.” We’d talk, at first tentatively, and then they’d open up until they got too nostalgic and teary eyed. This happened whenever we went through old family photos, of which there must have been hundreds. My father had insisted on a pictorial record of his children’s lives—a tradition that stopped a few years after the family moved to Sana’a. It was as if the new life was not worth documenting. I saw the look on my sisters’ faces as they gazed at their younger selves. Pictures of them in swimsuits on our summer vacations in Alexandria were quickly thrown back to the bottom of the pile. It was one thing to see their younger selves but another to recall the freedoms that came with that youth. Later during that visit, I put a handful of those old black-and-white photos in an envelope and dropped it in my briefcase. I had an unsettling fear that my sisters themselves or one of my brothers would destroy the photos. (So far this hasn’t happened, but I know that when I published one of them many years later for a

Globe and Mail

article, they were mad at me for months.)

I tried to find something that connected the pictures with the flesh and blood. And yes, there were traces of my old girls. The same generosity with whatever little cash they had. Hoda spent most of her salary buying clothes and toys for her nephews and nieces, whose parents were struggling just to house and feed them. Every few months, rent from properties in Aden that my uncle there collected and sent in moneybags with trusted travellers on a bus (can you imagine that?) was distributed evenly among the siblings, but in months when one of my brothers was going through a rough patch—a sick child, unemployment, overdue tuition—my sisters were the first to pass along their share to whoever needed it the most. Despite such generosity, money turned into a constant source of argument and stress. Over here, we’d turn to credit cards, overdrafts and lines of credit to make up the shortfall. None of my siblings had a credit card or an overdraft. Receiving a line of credit was simply accepting money from one brother or sister and repaying it if and when the situation changed. Even my mother, who seemed to have forgotten much of her past life, got involved in discussions about money and expenses. She felt that the little that my sisters bought for themselves was excessive and a sign of vanity. They started hiding from Safia whatever they bought, or only indulging in small things she wouldn’t notice: earrings or perfume.

Like my sisters, Safia rarely discussed the past and lived for the present. My father’s name was mentioned only once and in passing; she still blamed him for dragging the family back to Yemen. The past came with too heavy an emotional cost to relive. And the future as a concept was loaded with worry about a country that had been spiralling deeper into debt and poverty for over a decade. Safia seemed content to live in her room and watch TV for hours. Her last outing had been a trip to the dentist nearly six months before. I still remember how nice she always smelled during my visit, even though she couldn’t take a daily bath anymore. Still, she insisted on changing her clothes and using traditional scents to keep herself refreshed. She looked somewhat self-conscious about using her hands to eat in front of me instead of the spoon that my father taught her to use when she was a young mother. She refused to let me drink tap water in case I got sick, but she herself wouldn’t touch the bottled water. A waste of money, she’d say. A week into my visit she noticed that Motaz, my partner in Canada, was calling every few days. “He must really love you,” she said in as neutral a statement as she could muster. I don’t know if by then she’d really figured out my true relationship, but that remains my only delightful memory of that difficult trip.

The most difficult part, however, came halfway through it when Helmi insisted that I visit my father’s grave and say the traditional prayer for the dead—the

fatiha

, the opening chapter of the Quran, which by that point I had forgotten and had no desire to recite. I protested as much as I could, but he wouldn’t listen to any objection. To him, going back to Canada without making that pilgrimage was one act of defiance he wouldn’t tolerate. The entire visit took less than five minutes. It was an unmarked grave near the very front of an unremarkable burial ground. The local guard guided us to it, while children and poor widows stood nearby waiting for us to hand over alms. Once again, I felt like a voyeur on a scene of my own life. Wasn’t I just buying a round of drinks at a bar on Queen Street in Toronto only two weeks before? Wasn’t my biggest decision back then whether to take a cab home or wait for the streetcar? How had I suddenly found myself standing in a cemetery on the edge of Sana’a with a brother who proceeded to recite from the Quran as the un-merry widows waited for handouts? Something told me that even my father—the old Mohamed, who was chased out of Aden apartments by angry fathers and husbands and who took pride in speaking like an Englishman—would have found that scene a little too operatic. He would probably have told me to go home and salvage the rest of the day. I’d agree, but to me going home meant boarding a plane back to Frankfurt and connecting with the first flight home to Toronto, where I got to review performances and not act in them.

I returned to Toronto late in July with a heavy heart and an unspeakable sadness, but also with one more affirmation that my world and my family’s had diverged so totally that there could never be a chance of reconnecting. There was no more halfway point like my sister’s place in Liverpool. The pressures of that visit showed up in my relationship with Motaz, which went into two years of on-again, off-again, until it was over for good. He remained part of my Toronto family for a few more years until he decided to go to Beirut and give up his dreams of making it as a choreographer. Emotionally, I was too exhausted to consider giving or receiving love. It was easier to think of the difference between me and the family in intellectual terms and from a certain safe distance. To return from Yemen and in forty-eight hours be sitting in a Toronto theatre reviewing a classic production at Harbourfront or interviewing celebrities for

Globe Television

magazine sometimes was more than my mind could comprehend. The two lives couldn’t coexist. One of them had to be killed off, for good this time.