Introduction to Tantra: The Transformation of Desire (9 page)

Read Introduction to Tantra: The Transformation of Desire Online

Authors: Lama Thubten Yeshe,Philip Glass

Tags: #Tantra, #Sexuality, #Buddhism, #Mysticism, #Psychology, #Self-help

According to these methods, the first thing we need is a sense of equanimity, or equilibrium. Just as level ground is the basis on which you build a house, so too is equanimity—an unbiased attitude toward all other beings—the foundation for cultivating bodhichitta. The experience of past meditators is that when you have achieved such equilibrium, you can cultivate bodhichitta quickly and easily. However, because our habit of discriminating sharply between friends, enemies, and strangers is very deeply rooted within us, such even-mindedness is not easy to achieve. With our tremendous grasping desire we become attached to and cling to our dear friends, with aversion and hatred we reject those we do not like, and with indifference we turn a blind eye to the countless people who appear to be neither helpful nor harmful to us. As long as our mind is under the control of such attachment, aversion, and indifference, we will never be able to cultivate precious bodhichitta in our heart.

Equanimity is not an intellectual concept; it is not just another thought or idea to be played around with in your head. Rather, it is a state of mind, a specific quality of consciousness or awareness to be attained through constant familiarity. For this to happen you have to exert a great deal of effort. In other words, you have to train your mind and transform your basic attitude toward others. For example, when I first encounter a group of new people at a meditation course, say, I feel the same toward each of them. I have not met any of them before—they seem to have suddenly popped up like mushrooms—and I have not had time to develop attachment or aversion toward any of them. They all seem to be equal to me. If I take this unbiased feeling of equality that I have toward these new, unknown people and apply it both to my dear friends to whom I am attached and to my enemies and critics whom I dislike, I can start to develop true equanimity toward everyone.

There is a detailed meditation technique for the full cultivation of such equilibrium. In brief, you imagine yourself surrounded by three people: your dearest friend, your worst enemy, and a total stranger. One way is to visualize your friend behind you and the enemy and stranger in front with all other beings in human form massed around you. Having surrounded yourself in this way, you carefully examine the feelings you have toward each of the three people and analyze why you have categorized them as you have.

When you ask yourself, “Why do I feel close to just one of these people and not to the others?” you will probably discover that your reasons are very superficial, based on a few selected events. For example, perhaps you call the first person a friend because whenever you think of her you remember instances of her kindness or affection. And the second person appears to be your enemy because you remember some particularly nasty things he has done or said to you. As for the third person, the reason you call him a stranger is that you have no memory of his having ever helped or harmed you.

Your reasons for these different reactions are in fact arbitrary. If you search your memory honestly you are certain to find many instances when the three people you are thinking about did not fit comfortably into the categories you have so rigidly placed them. You may very well recall times when the enemy you now despise so much acted kindly toward you, when the friend you now care for so much provoked anger from you, and even when the person you are now indifferent to once meant a great deal to you. If you really think about this there is no way you can continue to see these people in the highly prejudicial way you do now. And when you reflect that each living being has, over beginningless past lifetimes, done the same kind and unkind things to you as the friend and enemy of this life, you will come to see that all are equal in having been friend, enemy, and stranger to you over and over again.

By training your mind in this way, your feelings of attachment to your friend, aversion to your enemy, and indifference to the stranger will begin to subside. This is the sign that you are beginning to experience a measure of equilibrium. Hold onto this feeling, and eventually, with practice, it will become an integral part of your mind.

Meditating on equilibrium is the best way of producing good mental health.

Instead of paying a hundred dollars an hour to a therapist, meditate on equilibrium! Close your eyes and ignore all physical sensations. Abandon the five sense perceptions and allow yourself to sink deeply into intensive awareness of your mind’s experience of equilibrium. You will definitely become more balanced, open, and peaceful. After even ten minutes of this type of meditation you will come out into a different world.

There is a common misconception about the development of equilibrium.

Some people think that it means becoming indifferent to everyone. They are afraid that if they lessen their attachment to their family and friends, their love and affection will disappear. But there is no need to worry: with true equilibrium there is no way we can close our heart to anyone.

The more we train ourselves to see the basic equality of everyone—having overcome our habitual tendency to stick them rigidly into categories of friend, enemy, and stranger—the more our heart will open, increasing immeasurably our capacity for love. By freeing ourselves from prejudicial views we will be able to appreciate fully that everyone, without exception, wants and deserves to be happy and wishes to avoid even the slightest suffering. Therefore, from the basis of equilibrium we will be able to cultivate universal love, compassion, and eventually the full realization of bodhichitta, the open heart dedicated totally to the ultimate benefit of all.

BODH I CH I TTA I S NECESSARY FOR P RACTI CI NG TANTRA

As a prerequisite for the successful practice of tantra, the development of bodhichitta is absolutely necessary. It has been said by all masters that to be properly qualified to practice tantra, we must possess very strong bodhichitta motivation. Truly qualified tantric practitioners wish to follow the speediest path to enlightenment, not with the desire to gain quick liberation, but because they have unbearable compassion for others. They realize that the longer it takes them to achieve enlightenment, the longer everyone who needs help will have to wait. The lightning vehicle of tantra is therefore intended for those who wish to help others as much as possible, as quickly as possible.

Although it is true that bodhichitta is the most important prerequisite for tantric practice, in fact, it is more accurate to say that the opposite is true: that the purpose for practicing tantra is to enhance the scope of one’s bodhichitta.

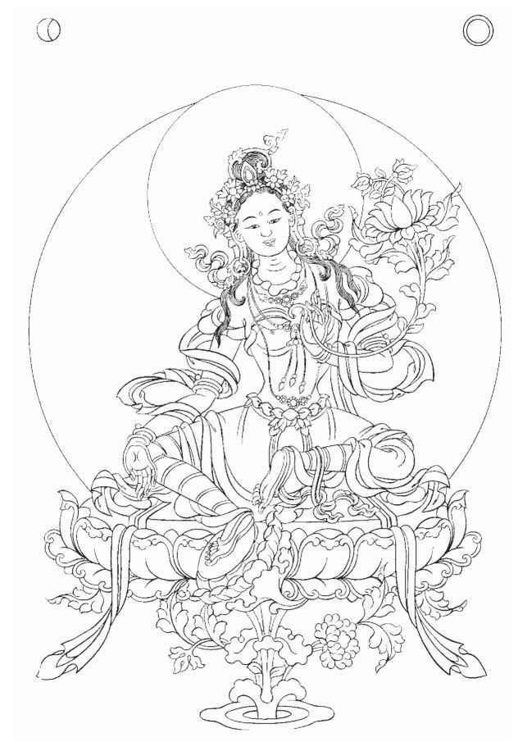

There are so many tantric deities—Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Tara, and the rest—into whose practice you can be initiated; there are so many deities you can meditate upon. But what are all these deities for? What is the purpose of all these practices? It is nothing other than developing and expanding the dedicated heart of bodhichitta. There is really no other reason for all these deities. In fact, all tantric meditations without exception are for the sole purpose of developing strong bodhichitta.

Take the practice of thousand-armed Avalokiteshvara, for example. The whole reason for having your consciousness manifest as a divine light-being with one thousand arms is so that you can lend a hand to one thousand suffering beings. What other reason could you have for wanting so many arms? And, if you do not feel comfortable manifesting in this way, you can always relate your meditation to your own culture and manifest your inner being as Jesus, Saint Francis, Kwan Yin, or any other holy being.

What we have to understand is that Avalokiteshvara and Jesus, for example, are exactly the same; the essential nature of each is complete selfless devotion in the service of others. Therefore, when we try to be like them, through the practice of tantra, prayer, or any other method, it is only to be able to serve others in a similarly selfless way. This selfless dedication to others is the true meaning of bodhichitta and that is why bodhichitta is not only the major prerequisite of tantra, it is also the most important fruit of this practice.

Tara

Dissol ving Se l f -Cre a te d Limita tions

TH E BURDEN OF MI STAKEN VI EWS

SO FAR WE HAVE SEEN how two of the prerequisites for pure tantric practice, renunciation and bodhichitta, help create space for us to discover our essential nature. Renunciation loosens our habitual grasping at pleasure and reliance upon externals for satisfaction, while bodhichitta opposes the self-cherishing attitude with which we focus upon our own welfare to the neglect of others.

Now we will consider the third basic prerequisite: cultivation of the correct view.

In this context the correct view means the wisdom that clearly realizes the actual way in which we and all other phenomena exist. This wisdom is the direct antidote to all the mistaken conceptions we have about who we are and what the world is truly like. As long as we are burdened by these misconceptions, we remain trapped in the world of our own projections, condemned to wander forever in the circle of dissatisfaction we have created for ourselves. But if we can uproot these wrong views and banish them completely, we will experience the freedom, space, and effortless happiness we presently deny ourselves.

Realizing the correct view of reality is not something mysterious. It is not a matter of staring up into space and praying for a glimpse of the truth. It is not that the wrong view is down here on the ground while the right view is somewhere up in the sky. Nor should we think that the wrong view dwells in the polluted cities of the West while the right view is to be found in the pure air of the Himalayas. It is nothing like that. The right view is available anywhere and everywhere, at all times. The beautiful face of reality exists within all phenomena, right here and how. It is only a matter of removing the layers of our own projections obscuring the pure vision of reality. The fault is ours, and the solution is ours.

Whenever we fix upon the idea that we exist in a certain specific way, we are hallucinating. Every time we look at ourselves in a mirror we have such a fixed idea—“How do I look today? I don’t want people to see me looking like that!”—although, in reality, we are changing all the time. We are different from one moment to the next, but still we feel we have some sort of permanent, unchanging nature.

Our view of the external world is just as deluded. Our sense organs habitually perceive things dualistically; that is, every sensory object that appears to us seems to exist from its own side as something concrete and self-contained. We think that merely because we can see, hear, smell, taste, and touch these objects they must be real and true, existing solidly out there in their own right, just as we perceive them. But this concrete conception we have about how they exist is also a hallucination and has nothing whatsoever to do with their reality.

It takes time, training, and clear-minded investigation to cut through these deeply ingrained wrong views and discover the actual way in which things exist. But we can begin this process right now merely by being a bit skeptical about what appears to our mind. For example, as soon as we realize that we are holding onto a solid view of ourselves—“I am like this,” “I should be like that”—we should remember that this view is nothing but a fantasy, a momentary projection of our mind. Nor should we passively accept that external phenomena exist in the concrete self-contained way they appear to us.

It is better to be slightly suspicious of what our senses and ordinary conceptions tell us, like the wise shopper who, when buying a used car, does not immediately believe everything the salesman claims about it.

DREAMS AND EMP TI NESS

If we want to understand how we are ordinarily misled by our false projections and how we can begin to break free from their influence, it is helpful to think of the analogy of our dream experiences. When we wake up in the morning, where are all the people we were just dreaming about? Where did they come from? And where did they go? Are they real or not? Of course not. These dream people and their dream experiences all arose from our sleeping, dreaming mind; they were mere appearances to that mind. They were real only as long as we remained in the dream-state; to the waking mind of the next morning they are only an insubstantial memory. While we were asleep they seemed so true, as if they were really out there, having a concrete existence quite apart from ourselves. But when we wake up we realize that they were only the projections of our dreaming mind. Despite how real they seemed, these people in fact lack even an atom of self-existence. Completely empty of any objective existence whatsoever, they were only the hallucination of our dream experience.