Inventing the Enemy: Essays (21 page)

Read Inventing the Enemy: Essays Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

As Jeffrey Burton Russell has shown in his

Inventing the Flat Earth

(1991), many influential books on the history of astronomy still studied at school claim that Cosmas’s theory became the prevailing view throughout the Middle Ages. They also claim the medieval church taught that the Earth was a flat disc, with Jerusalem at the center, and that the works of Ptolemy remained unknown throughout the Middle Ages. The fact is, Cosmas’s text—written in Greek, a language the medieval Christian had forgotten—became known in the Western world only in 1706 and was published in English in 1897. No medieval writer knew of it.

A first-year pupil at a secondary school can easily work out that if Dante enters the funnel of hell and leaves from the other side, seeing unknown stars from the slopes of Mount Purgatory, this means he knew perfectly well that the Earth was round. But Origen, Saint Ambrose, Albertus the Great, Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, and John of Holywood (to mention just a few) were all of the same view. The point of dispute at the time of Columbus was that the calculations made by the learned men of Salamanca were more accurate than his. They claimed that the Earth, which was certainly round, was larger than our Genoese voyager imagined, and it was therefore pure folly to try to circumnavigate it. Columbus, however, a fine navigator but a useless astronomer, thought the Earth was smaller than it was. Neither he nor the learned men of Salamanca, of course, suspected the existence of another continent between Europe and Asia. Though they were right, the doctors of Salamanca were wrong; and Columbus, though wrong, faithfully pursued his error and was right—through serendipity.

How did the idea develop that in the Middle Ages people thought the Earth was a flat disc? In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville (though hardly a model of scientific accuracy) calculated the equator to be eighty thousand rods long. Therefore, he thought the Earth was round. But among Isidore’s manuscripts is a diagram that influenced many representations of our planet, the so-called T-O map.

The upper part represents Asia—at the top because, according to legend, earthly paradise was to be found in Asia. The horizontal bar represents the Black Sea on one side and the Nile on the other, and the vertical bar is the Mediterranean, so that the quarter circle on the left represents Europe and that on the right, Africa. All around it is the great circle of the ocean.

The impression that the Earth was seen as a circle is given by the maps illustrating the

Commentary on the Apocalypse

by Beatus of Liébana. This text, written in the eighth century but illustrated by Mozarabic illuminators in later centuries, was to have a major influence on the art of the Romanesque abbeys and Gothic cathedrals—and its model is to be found in countless other illuminated manuscripts.

How was it possible for people who thought the Earth was round to draw maps showing it to be flat? The first explanation is that we do the same ourselves. Criticizing the flatness of these maps would be like criticizing the flatness of our modern-day atlas. It was a naive and conventional form of cartographic projection.

It could be pointed out that over the same centuries the Arabs had produced more accurate maps, though they had the bad habit of representing north at the bottom and south at the top. But we have to bear in mind other considerations. The first is suggested by Saint Augustine, who was well aware of the debate begun by Lactantius about the cosmos in the shape of a tabernacle, but was at the same time aware of the views of the ancients on the roundness of the globe. Augustine’s conclusion is that we should not place too much emphasis on the biblical description of the tabernacle because, as we know, the holy scriptures often speak through metaphor, and perhaps the Earth is round. But since knowledge about whether it is spherical or not doesn’t help us to save our souls, we can ignore the question.

This doesn’t mean, as has often been suggested, that there was no medieval astronomy. We need only cite the story of Gerbert d’Aurillac, the tenth-century pope Sylvester II, who in order to obtain a copy of Lucan’s

Pharsalia

promised an armillary sphere in exchange; not realizing that the

Pharsalia

had been left incomplete on Lucan’s death, upon receiving an incomplete manuscript he gave only half of the armillary sphere in exchange. This indicates the great attention given to classical culture during the early Middle Ages, but it also indicates the interest in astronomy at the time. Ptolemy’s

Almagest

and Aristotle’s

De caelo

were translated during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. As we all know, astronomy was one of the subjects of the quadrivium taught in medieval schools, and in the eighth century John of Holywood’s

Tractatus de sphaera mundi,

based on Ptolemy, was to be the undisputed authority for centuries to come.

Yet it is also true that geographical and astronomical notions had long been confused by the ideas of authors such as Pliny or Solinus, for whom astronomy was certainly not of uppermost concern. The picture of the Ptolemaic cosmos, formed perhaps indirectly through other sources, was theologically most credible. Each element of the world, as Aristotle taught, had to remain in its proper natural place, from which it could be moved only by violence and not by nature. The natural place for the earthly element was the center of the world, whereas water and air had to remain in an intermediate position, and fire was at the edge. It was a reasonable and a reassuring picture, and this idea of the universe enabled Dante to imagine his journey into the three realms of the afterlife. And if this representation did not take account of all celestial phenomena, Ptolemy himself contrived to introduce adjustments and corrections, such as the theory of epicycles and deferents, according to which, in order to explain various astronomical phenomena such as accelerations, positions, retrograde motions, and the variations in distances of various planets, it was supposed that each planet rotates around the Earth along a larger circle, called the deferent, but also moves in a small circle, or epicycle, around a point C of its own deferent.

Lastly, the Middle Ages was a period of great travel, but with the roads in disrepair, great forests to pass through, and stretches of sea to be crossed at the mercy of buccaneers, there was no possibility of drawing adequate maps. They were purely indicative, like the instructions in the

Pilgrim’s Guide

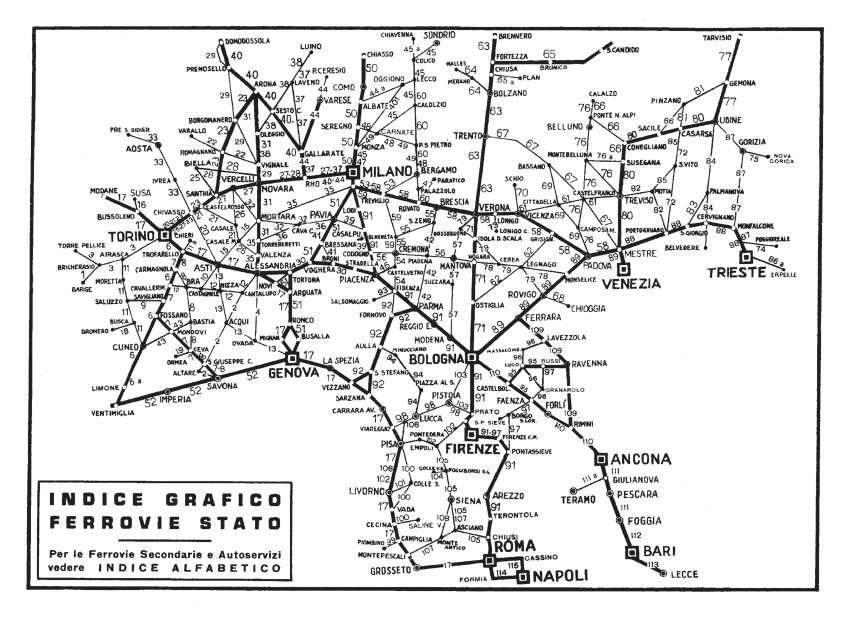

at Santiago de Compostela, which said, more or less, “If you want to get from Rome to Jerusalem, head southward and ask along the way.” Now, try thinking of the rail maps you find with train timetables. No one could deduce the exact shape of Italy from that series of junctions, each perfectly clear in itself when you have to take a train from Milan to Livorno (and realize that you have to change at Genoa). The exact shape of Italy is of no interest to anyone traveling to that station.

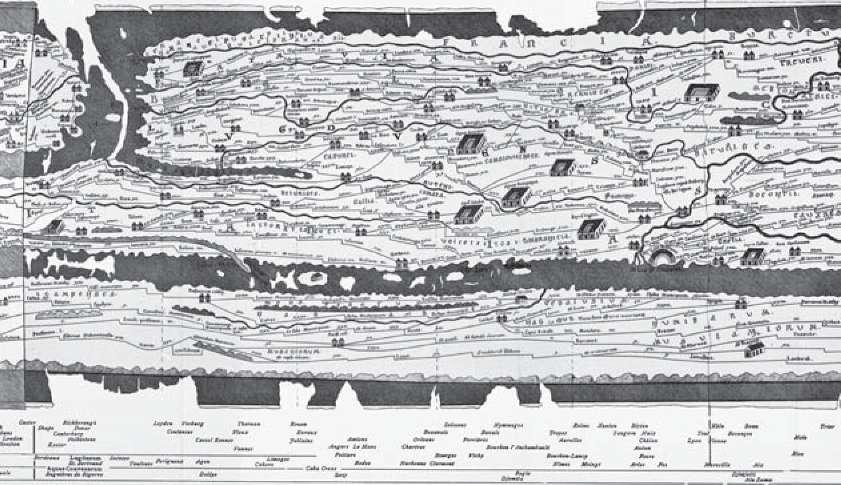

The Romans built a series of roads that linked every city in the known world, but this is how those roads were represented in the map known as the

Tabula Peutingeriana,

named after the man who had rediscovered it in the fifteenth century. The upper part represents Europe, with Africa below, but we are in exactly the same situation as the railway map. From this map we can see the roads, our points of departure and arrival, but have absolutely no idea about the shape of Europe, or the Mediterranean, or Africa—and the Romans certainly had a much clearer notion of geography than this. They were not interested in the shape of the continents, but rather in whether, for example, there was a road that would take them from Marseille to Genoa.

Then again, medieval journeys were imaginary. The Middle Ages produced encyclopedias,

Imagines mundi,

whose authors tried as far as possible to satisfy the taste for wonder, writing about far-off, inaccessible lands, and these books are all written by people who had never seen the places they are describing—the force of tradition at that time was more important than experience. A map did not seek to represent the form of the Earth but to list cities and peoples along the way.

Once again, symbolic representation was more important than empirical representation. In many maps, the illuminator was most concerned about placing Jerusalem at the center of the Earth, rather than showing how to get there. Yet most maps of that period represent Italy and the Mediterranean fairly accurately.

One last consideration. Medieval maps did not have a scientific purpose but instead responded to the audience’s need for wonder, in rather the same way that popular magazines today show us that flying saucers exist and we are told on television that the pyramids were built by an extraterrestrial civilization. The creators of these maps looked up at the sky with the naked eye to see comets, which the imagination immediately transformed into something that (today) would confirm the existence of UFOs. On many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century maps with a reasonably accurate cartographic layout, mysterious monsters are depicted in the lands where they are supposed to live, and are reproduced on the map in a not entirely mythical fashion.

So let us not be too critical of medieval maps. It is with them that Marco Polo arrived in China, the Crusaders in Jerusalem, and perhaps the Irish or the Vikings in America.

A short aside—is it really true, as legend suggests, that the Vikings reached America? We all know that the real revolution in medieval navigation came with the invention of the stern-mounted hinged rudder. On Greek and Roman ships, as well as those of the Vikings and even those of William the Conqueror who landed on the English coast in 1066, the rudder consisted of two rear side-oars, operated in such a way as to set the intended direction of the boat. The system, apart from being fairly exhausting to use, made it practically impossible to maneuver large wooden vessels. Above all, it was impossible to sail against the wind; to do so, it was necessary to tack—to move the rudder so that each side of the boat faced alternately into the wind, first one side and then the other. Sailors therefore had to limit themselves to navigating close to shore, following the coastlines so that they could take shelter when the wind was unfavorable.

The Vikings (and the same was true for the Irish monks) could never, therefore, have sailed from Spain to Central America, as Columbus would later do. But the picture changes if we imagine they first took a route from Iceland to Greenland, and from there to the Canadian coast. Looking at a map, we can easily see how skilled mariners in longships could succeed (with who knows how many shipwrecks along the way) in reaching the far north of the American continent and perhaps the coast of Labrador.