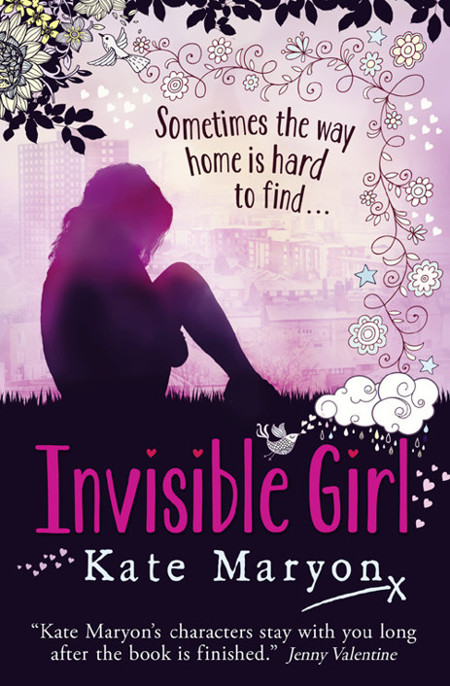

Invisible Girl

Authors: Kate Maryon

For Dawne, Susie, Susannah, Rachel, Helen,

Emma, Becky and Clea…

May we dance in this glorious fire of tea-drinking, wine-sipping, heart-sharing friendship until our old bones return to dust and all that laughter and all those tears are heard as Love, echoing through the glittering hallways of eternity. X

For Mathilda, Freddie and Ella…

For your truly wonderful dads, Mike and Pete, you touch my heart with your enthusiasm and generosity – thank you both so much. x

Foreword by Andy McCullough – Head of Policy for the charity Railway Children

Y

ou may be surprised to know 100,000 children in the UK run away from home or care every year. Many are thrown out, no longer wanted in the family. The majority of children say family problems and issues are the main reason for them running.

Often when you end up running away you feel you have got rid of your problems; however, you usually substitute them for other problems. Being out on the streets is lonely, cold and really dangerous. We know that there are always people who will exploit young people and use them for profit and power.

I have worked in the field of social care for over twenty-seven years, but some of my training was as a child myself, spending a lot of time on the streets, having run away. I met a lot of good people whilst out there, people who had grown up in care, been kicked out by their family or had become detached, but always, like a dark shadow, there were people who wanted to use you to make sure they were better off.

Gabriella’s story is an important one to hear. Who knows, it may make you think a little differently when you pass a child on the streets…

Railway Children is a registered charity, no.1058991

Visit www.railwaychildren.org.uk

Most days drift by like clouds. Others burn deep into your life and make a blister, like a bright white moon in a black night sky.

And you’re left wondering, forever.

Then, I might as well have been invisible for all Dad and Amy cared. They’d been busy making massive decisions about my life without even thinking about me, or bothering about how I

might feel. They’d obviously been plotting and planning for weeks, whispering under the covers at night, painting the walls of our flat with lies.

The day had been creeping towards me like a tiger in the dark with its amber eyes glinting, for ages. The shouting had been getting worse. Dad had started spending more and more money we didn’t have. He’d broken his promise and started using credit cards again, to keep Amy happy. But it didn’t work. Amy just got madder and madder, her screeching making her face flush pink and her lips turn white with rage.

What’s strange is that the day it actually happened everything seemed so normal. Dad ignored me, his eyes glued to

Daybreak

on the telly and Amy hogged the bathroom for so long I thought I was going to wet myself. In the end I couldn’t wait any longer, so I picked up my bag and raced off to school with a piece of toast and jam between my teeth without even saying goodbye.

If I’d known I was never going to sleep in my bed again or sit on our sofa or lie in our bath under the bubbles, I might’ve snuggled down in the warm a bit longer, soaked up that feeling of home. I might have given Dad a kiss, begged him to change his mind; at least I could’ve asked him why. I’d definitely have grabbed more toast.

Toast would’ve been good because I had no idea how hungry I’d get, or how cold.

The most annoying thing though, apart from what Dad did, is that he didn’t put my little photo of Beckett with the letter. I hadn’t seen or heard from Beckett or Mum for seven years, nothing at all since the day they left. So not having the photo made everything so much harder.

T

hings were fine when it was just Dad and me. We never really talked about anything important, but we were OK. I missed Beckett loads and wished he could’ve stayed with us, but I was relieved Mum had gone. I hadn’t felt scared in the morning for ages. I hadn’t had to hide under my covers at night, smothering my sobs by biting on Blue Bunny’s ear. And although Dad never bought flowers, like my best friend Grace’s mum does every Friday, our flat was still nice; it was our cosy home.

But that was before Amy came along and ruined everything. I could tell she didn’t want me around from the start. The way she kept glaring at me and sighing; the way she got into a huff if Dad so much as even looked at me. She kept clinging to him like tangled ivy up a wall, batting her spidery eyelashes, whispering in his ear. If I were a piece of old furniture, Amy could have taken me along to the tip with all the other old stuff that belonged to Mum. It would’ve made it much easier for her to chuck me out of her life, to pretend I’d never existed.

The worst thing was, Dad didn’t even tell me she was moving in. I was there, digging through the iceberg in the freezer, looking for chips to go with eggs for our tea and she arrived with a million black bin liners, bulging with stuff…

“Where on earth d’you expect me to put my things, Dave,” she says, clattering up the hallway, “when this place is so full of junk?”

She opens and closes our cupboard doors, slams around the flat like she owns it. She goes into my room and starts rearranging my stuff, kicking my scrapbook things under my bed, picking bits of fluff off the floor. I can’t believe my eyes. She stands there with her hands on her hips, tutting like a bird, rolling her eyes like a mad person.

“Put them wherever you like, babe,” Dad says. “You know, make yourself at home.”

I wanted to punch Dad then, to wake him up. He’d gone all floppy and pathetic like he used to be with Mum, like a big stupid fat lump of dough. Why did he do this? Why can’t he tell her to get lost so we can eat our eggs and chips in peace and watch the telly?

Dad opens his arms wide and pulls Amy in so tight his big belly bulges like whale blubber around her.

“And you, Mister,” she says, pulling away from him and jabbing at his belly with her sharp red fingernail, “need to shed a few pounds.” She pats him like he was her puppy. “Can’t have my man being a big old fathead, can I?”

“Look, babe,” says Dad, slapping Amy’s bum, “what’s mine is yours. You’re the woman of the house now. Do what you like with the place. I don’t care.”

That was the wrong thing to say because:

1. I do care.

2. Amy does just that.

Later on she starts pulling the flat apart, rearranging it, putting all her stinky air freshener plug-in things and stupid ornaments all over the place. She clutters up the bathroom with loads of body scrubs and sprays and mountains of make-up.

“Ew!” she says, leaning over the chip pan, almost choking me to death in a swirl of perfume. “What on earth d’you call that?”

My cheeks burn hotter than the chip fat.

“Egg and chips,” I say. “I’m making tea for Dad.”

Amy laughs like a hyena in

The Lion King

. She rests her hand on her forehead, dramatically, and starts staggering about the kitchen on her pink high heels.

“You’re not seriously gonna eat that rubbish she’s making you, Dave, are you? You might die from food poisoning! Quick! Quick! Fumigate the place! We might all die!”

Dad leans against the fridge and sighs.

I freeze, stiller than a statue, and watch the edges of the chips frizzle and burn while these huge invisible hands slide inside me and scrunch my tummy up tight.

“Nah, babe,” Dad says. “You’re right! We’ve got a real woman in the house now; we don’t need to eat that old muck. You can cook proper grub for us, right, babe?”

Amy laughs and rolls her eyes, the little red veins threading over them like rivers.

“If you think I’m gonna be a slave to your kitchen, Dave,” she says, poking his belly, “you’ve got another think coming. I’m your girlfriend, remember, not your freaking wife!”

Dad opens the fridge and peers inside. He sniffs a carton of gone-off milk, reeling backwards with the stink.

“How about a takeaway?” says Amy. “You know… celebration time!”

She starts digging in his pockets for his wallet, tugging at his shirt, her bony hands moving all over him. Dad pulls away; his ears glowing as red as a throbbing sore.

“Not tonight, eh, babe?” he says, nudging her away. “Let’s save it for the weekend. We’ll have the egg and chips, shall we? Gabriella’s done them now. I promised her we’d sit together to eat and watch telly. Shame to waste them.”

Amy puckers her lips so tight they remind me of a hamster’s bottom.

“You’re not gonna turn into a mean man now I’ve moved in, are you, Dave?” she says, jabbing her elbow in his ribs. “You know what they say about mean men.”

A line of sweat bubbles above Dad’s top lip. He pulls his wallet out of his pocket and digs his fat fingers in to get at the cash. He sighs and all his strength kind of drains away like water.

“All right then,” he says, “anything you like.” He turns to me. “Gabriella, run down to Chang’s, will you?”

“Good idea, Dave,” says Amy, giggling, wriggling her way into his arms, nibbling at his ear. She glares at me and holds Dad tight like she’s won him as a prize.

I ignore Dad and watch the burny bits creep along the chips until every one is black and smoke is billowing into the kitchen. Amy starts flapping her arms like mad.

“I’m gonna choke, Dave!” she squawks. “Open the window, will you, you stupid old fat bum!” She puts her hands on her hips and stares at me. “I’m the woman of the house, Gabriella Midwinter, your dad just said so. So you’ll keep your grubby hands out of my kitchen and get sharpish at tidying up that bedroom of yours. Do you hear?”

My heart thumps in my ears. I glare at her through the swirls of black smoke. My room is none of her business.

“I like it in a mess,” I say. “I know where everything is and Dad doesn’t mind.”

She moves towards me, her shoes clip-clopping on the kitchen floor, her waggling finger pointing. “Well, young lady,” she says, pushing her face so close to mine I can see the streaks of fake tan on her cheeks, “things are about to change round here. I’m the boss now. So you’d better get used to it.”

My legs are trembling. “But it’s not your flat, Amy,” I say. “It’s ours. And Dad’s the boss. I like my room how it is.”

“This place is a disgrace,” she snaps. “The council would slap a health warning on it if they came for a visit!”

I wish Dad would charge forward and pull her away from me. I wish he’d tell her I can have my room how I like. Instead, he pulls a can of lager out the fridge, snaps it open and takes a long cool sip. He pours a glass of wine for Amy that reminds me of blood, and looks at her and then at me. He sighs, handing me a wodge of cash. I glare at him.

“Dad!” I say. “We can’t afford takeaway—”

“Gabriella,” he interrupts, “don’t be boring. Be a good girl and go and get the food.”

“And make sure you get my order right, Miss Flappy Ears,” says Amy. “I want beef with black bean sauce.”

I’m glad to leave the flat. The air outside is warm and the sun’s turning red in the sky. I stare at it for ages, watching it sink lower and lower. I wish I had some paints with me. I wish I were a proper artist with a real easel and proper brushes and a little stool and an actual canvas. I would really love to paint that sun.

The queue at Chang’s is long. But I don’t mind. I sit and watch the fishes swim round and round the tank, in and out of a little blue castle that’s nestled in the gravel. Round and round and round, weaving through the plants. I wonder if they ever get bored?

I feel like a fish sometimes, going from home to school and back again. Round and round, to town or the park or Grace’s. Dad and me never go anywhere fun. We never do anything special. If Grace invites me on one of her famous expeditions my tank gets a little bit bigger for the day, but it doesn’t happen very often. Zoe and Elsie from my class have amazing lives full of glitter and lip-gloss shimmer, full of popcorn and pony trekking and soft pink leotards with white net tutus for ballet dancing.

I like Friday afternoons when the Play Rangers come to our estate and make us hot chocolate and we toast marshmallows on a fire. We build camps from blue plastic and rotten wood, and run around playing games, squealing at the top of our lungs. But I can still see our flat from the green. I can still see Mrs McKlusky’s tartan slippers fringed with the soft tufts of cotton, shuffling about. I can still hear her mumbling words rude enough to make your ears sting.

Grace came to Play Rangers once and thought it was the best thing ever. My tummy felt warm then, that I had something special to share. Dad keeps promising he’ll come and watch us one day. He keeps promising to fix us a rope swing in the tree on the green.

I order crispy duck for Amy and wish I could tell Chang to put poison on it. But I don’t in case Dad eats it or me. I worry in case one of us dies or if Amy dies and Dad gets sent to prison. Sometimes my heart burns hot with worry. My tummy gets in tangles because who would care for me if Dad was gone? Grace is lucky. Grace has a nice mum

and

a nice dad. She has two grannies

and

a grandpa and all sorts of special aunties and uncles and cousins who send her things in the post. Things wrapped in shiny paper with ribbons so colourful I just want to snip them up and make beautiful patterns with the scraps.

When I get back home the flat is quiet with a note on Dad’s bedroom door saying,

DO NOT DISTURB

. I push my ear against the cold paintwork to listen. Dad’s laughing, Amy’s squealing, their music is blaring.

I grab a fork from the kitchen, shut myself in the front room and put the telly on so loud I know that Mrs McKlusky will bang on the wall with her broom.

I don’t care about Dad and Amy. I’m glad they’re not with me because I can stretch right out on the sofa with my feet up and all the cushions are mine. I can watch my favourite hospital programme in peace. There’s been this big car crash and people are dead, but some are still alive, groaning. My favourite paramedic girl with the soft, kind voice is coming to the rescue. I watch carefully, trying to work out how the make-up artists make all the gashes and bruises look so real.

When I’ve finished my chicken chow mein I lick my fingers and slide my tongue across my lips to keep the taste going on for a little bit longer. I dig into the mountain of prawn crackers, dipping them in the sweet chilli sauce, cramming them into my mouth, tasting them prickle and melt. Dad’s sweet and sour pork smells so good I can’t stop myself from dipping my fingers in its sticky red juice and licking them like lollipops.

And I know he won’t mind because you could easily lay my dad on the floor and wipe your muddy feet all over him and he wouldn’t say one thing. You could slap him round the face, like Mum used to, and he’d just slide off into the bedroom to hide. Like I’d slide under my bed and get as close to the wall as I could. As far away as possible, so she couldn’t get to me with her sharp slaps or see how much the big purple bruises they left on my skin hurt.

I can’t stop fretting that Dad’ll miss his tea and be starving. Amy’s food is sitting on the edge of the coffee table, staring at me, daring me to touch it. I won’t eat it. I’d never do that. But this idea starts swimming round and round my head like Chang’s fishes, pressing in on my skin.

I write ‘beef in black bean sauce’ on the lid so it looks like Chang made a mistake with the order. Then I peel off the lid and rest it on the side. I breathe in crispy duck dare. I put my face close and let spit dribble out and melt into the sauce. I stir my fork round and round then put the lid back on so neat that unless Amy is a detective she’ll never find out.

When my favourite lady on the hospital programme has finished crying into her boyfriend’s arms because she didn’t save the people in time, I watch this other one about cooking in Italy. They make this yummy red sauce and powdery cheese pasta with green basil sprigged on top. They show you the sights and it’s so real I feel like I’m actually in the car with the man with the rusty beard. I’m driving down the avenues of tall trees, past golden fields. I’m drinking the cappuccino hot milk froth with chocolate. Like it’s

me

, far away from here.

And when we get to the art gallery, in Florence, I hold my breath because the paintings are amazing. There’s one that’s so huge it’s impossible to work out how you might even paint it. It has this woman standing in a big shell and all these other people swooping and swooshing around her.

The marble sculpture of someone called

David

is the best. Grace would’ve laughed her socks off if she were watching because David’s naked. Imagine having a huge chunk of cool white marble in front of you, all the chisels and hammers you need. Imagine chipping away until you’re covered in white dust and your hands are sore and the person inside steps out and stops waiting forever for someone to find them.