Irish Ghost Tales (16 page)

Authors: Tony Locke

Suspecting trickery, the devil suggested the date of surrender should be on the last day of February twenty years hence and, after some haggling concerning the time, this was finally agreed. The first instalment was paid straight away, the second after seven years. The devil then requested to be taken to the old riding boot. He snapped his fingers and gold coins began to fill the boot until it was full to the top. This seemed to take a long time. What the devil did not know was that the boot had been placed over a hole in the floor, which led directly to the cellars of Galgorm Castle. The crafty doctor had cut away the heel of the boot. The devil realised he had been tricked and disappeared with an angry roar, promising vengeance in seven years. The doctor just smiled, stating he would look forward to their next meeting.

At the end of seven years, the devil reappeared. However, suspecting another trick, he refused to meet the doctor at the castle. Their meeting place took place at an old limekiln nearby. The doctor was already waiting for him by the edge of the kiln, with his old soft hat outstretched. This he required the devil to fill to the brim. The devil snapped his fingers and gold coins began to fill the hat but once more the doctor cheated; there was a thin slit in the crown of the hat, so the gold fell into the kiln below. Again the devil promised vengeance when he collected the doctor's soul in thirteen years' time.

When the devil arrived at Galgorm Castle he found the doctor in the old church. The so-called clergyman was pretending to read the Bible by the light of a candle. In a booming voice, the devil commanded him to rise and accompany him to hell, where he had a very special place set aside for him.

âJust a moment,' Doctor Colville said. He raised a hand. âLet me finish this portion of Holy Scripture. Promise me you'll wait just until my little candle burns out for you will have me for eternity.'

Reluctantly the devil agreed. With a cry of triumph, the doctor snuffed out the candle and placed it within the pages of the ironbound bible. âNow it will never burn down, nor will it be lit again, nor can you take it from within the sacred pages.'

Years passed until a time when the doctor was away in Belfast visiting friends. In his absence, an old maidservant was cleaning his study. It was a dark winter's evening and she looked around for some source of light. The doctor had left the Bible open on the table. The old servant saw the candle stump.

âHe'll not mind me having this wee bit of light on such a dark evening,' she said, lighting it. As soon as it had burnt away she heard a demonic laugh followed by thunderclap echoing through the castle. When the doctor arrived back from Belfast and heard what had happened, he turned pale and trembled.

âYou've condemned my soul to hell,' he told the old woman as he dismissed her from service.

However, Dr Colville was a crafty man and he was determined not to be outdone by the devil. He devised a plan: from that day onwards, every year as the end of February (the last day of February being the date agreed upon for the collection of the soul) approached, he would become more pious, reading the Bible, saying prayers and singing religious songs, all with the aim of keeping the devil at bay, until 1 March, when he would resume his old ways again and become as heartless as ever â until the middle of February the following year.

Finally, when one 28 February had passed and the great clock in the hall of Galgorm Castle struck midnight, Dr Colville laid aside his religious books and climbed the stairs to one of the upper rooms where some friends were gathered for an evening of gambling and drinking. Lifting a glass of brandy, he raised it in a toast to his company.

âA good swallow of brandy, a good game of cards. What better way to celebrate 1 March?'

One of his friends said, âBut it's not 1 March. Today is 29 February. It's a leap year.'

At this the doctor turned white and dropped his glass.

âWhat? A leap year? It can't be!'

He looked around fearfully for his Bible. Where had he put it? But it was too late. There came a hammering on the door like the rumble of thunder. When an old servant opened it, there stood a tall man in a green cloak. Ignoring the servant's protests he strode into the castle and up the stairs to the room where the doctor was cowering.

âIt's time that our bargain was completed, Dr Colville,' he said in a voice dripping with hate.

The doctor grovelled and protested, begging for a compromise, but without another word, the devil wrapped his cloak around the doctor and, with a puff of foul-smelling smoke, they disappeared in front of the astonished guests. Neither was ever seen again.

F

LORENCE

N

EWTON

,

THE

W

ITCH

OF

Y

OUGHAL

COUNTY CORK

I

n areas of Ireland that had been widely settled by the English, English law prevailed. So it was not unusual to find an English-style witchcraft accusation in an area such as Youghal, County Cork, which had been extensively settled by English puritans.

Since the mid- to late 1500s, the town had been considered âEnglish'. Sir Walter Raleigh had been one of its early mayors and the first potatoes from the New World were grown in Youghal. âEnglish ways' were said to prevail there. So it is not surprising that English beliefs in witchcraft also manifested themselves in the trial of Florence Newton in 1661.

It all began because of a disagreement between an old woman and a young girl. Florence Newton was committed to Youghal prison by the mayor of the town on 24 March 1661 to stand trial for witchcraft at the Cork assizes on 11 September. She was accused of bewitching a servant girl, Mary Longdon, who was called to give evidence against her at her trial.

Newton was a beggar woman who seldom worked and who went from door to door scrounging what she could. She had a nasty reputation and used this to intimidate people so she could get what she wanted.

Mary Longdon was the servant of a well-to-do local bailiff who went on to become mayor. She believed that her position gave her the right to airs and graces and she was thought by those who knew her to be a little bit snobbish.

Longdon accused Newton of threatening her because she refused to give her food from her master's table. Later she was confronted by Newton who she claimed kissed her violently.

Shocked by this, Longdon returned home. Shortly afterwards she fell ill and became subject to âfits and trances', which became extreme. She also started to vomit up all manner of odd things â needles, pins, horseshoe nails, wool, straw â and it would take three or four strong men to hold her down.

During these trances, she saw visions of Florence Newton, who would approach her and stick pins into various parts of her body. Longdon stated that the fits and trances only began after Newton had kissed her and that she âhad bewitched her' with her kiss. It is here that Newton sealed her own fate for, as Longdon finished giving her evidence, Newton pointed at her and said, âNow she is down.' At this, Longdon fell to the ground and had a violent fit, biting at her own arms, shrieking and foaming at the mouth, much to the distress of all in the courthouse.

Newton was ordered to recite the Lord's Prayer but after several attempts failed to do so. The trial now began to take on some of the characteristics of English witch-finding, with specific examinations of the accused taking place under the supervision of supposed âexperts'. Valentine Greatrakes (or Greatrix, as he is called in some records) seems to have operated in this case much in the same way as Matthew Hopkins in Essex. Why he involved himself in the case is unclear but it seems he was contacted by some of the Youghal citizens as he had professed to have knowledge of witchcraft and the methods used to interrogated suspected sorcerers.

The evidence against Newton was further strengthened when her jailer dropped dead. He was ill and it is probable that he had a stroke but his dying words were, âShe's done for me.' The trial concluded. She was indicted on two counts: first, the bewitching of Mary Longdon and, secondly, causing the death of her jailer, David Jones. The trial had been almost wholly conducted in an English manner and according to English law. It caused great interest in Youghal and further afield and was considered to be so important that the Irish Attorney General went down to prosecute. Sadly there is no record of the verdict and Florence Newton disappears from all records of the time. It is likely, however, that she was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged in accordance with the punishment prescribed by English law in such matters.

It is easy, with the benefit of hindsight, to dismiss these events as fanciful but to do so would be to dismiss the thinking of seventeenth-century Ireland. The lawmakers and rulers of this society were the educated people of the time. Witchcraft was a label they attached to anything they considered to be inexplicable and it also enabled them to cope with the changing ethos of the time.

The trial of Florence Newton offers an insight into the link between Irish and English society at the time. It reveals the tension, fear and anxiety that underpinned life in a seventeenth-century Irish plantation town.

L

ADY

B

ETTY

(1750-1807)

COUNTY ROSCOMMON

L

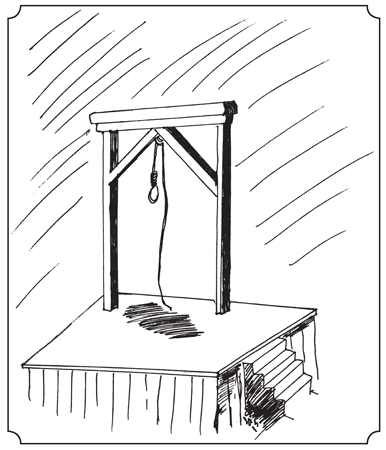

ady Betty was an infamously cruel hangwoman who worked in Roscommon jail in the eighteenth century. According to Sir William Wilde, she drew a sketch of each of her victims on the walls of her dwelling with a burnt stick.

Born into a tenant farmer's family in County Kerry, the woman who came to be known as Lady Betty married another poor farmer, named Surgue, and they had a family. Upon his death, Betty and her three children were left destitute.

She set out with her children on the long walk to Roscommon town to look for a better life. En route her two younger children died of starvation and exposure, leaving only her elder son. When they reached Roscommon, Betty and her son moved into an abandoned hovel and begged, borrowed and stole to eke out a living. She was known to have a violent, cruel temper. Whether it was because of this or the grinding poverty (or a combination of both), her son decided to leave and go to America to seek his fortune. He promised to return one day a rich man.

The years passed and Betty supplemented her meagre income by taking in desperate lodgers and travellers for a few pennies a night. One stormy night a traveller arrived at the door looking for a room. Betty took him in but she noticed how well dressed he was and saw that he had a purse full of gold, unlike her usual guests. The temptation proved too much. She waited until he was asleep, then stabbed him to death and robbed him. Tragically for her, as she was going through his belongings, she found papers that identified him as her son, unrecognisable after years apart. It has been suggested the reason why he had not identified himself to her was that he wanted to find out if she was still the violent, bad-tempered person he had known. Unfortunately for him, she was. Betty was arrested, tried for murder and sentenced to hang.

The day of her execution arrived and she was led to the scaffold together with others due to be hanged. Amongst the various thieves, sheep stealers and murderers were some Irish rebels and Whiteboys. However, because of local loyalty to the rebels, no hangman could be found, so the authorities did not know what to do. This was when Betty made her mark on history. She said to the sheriff, âSet me free and I'll hang the lot of them.' She killed twenty-five that day and, with the full support of the authorities, continued her gruesome work right across Connacht.

She lived rent-free in a third-floor chamber at the prison and although she was paid no salary she loved her work and never had to worry about food. She had a very public method of hanging: a scaffold was erected right outside her window and the unfortunate person had to crawl out, already noosed, and stand there as she pulled a lever, which would send the condemned to his or her death. She had a nasty habit of letting the bodies âdo the pendulum thing' while she sketched them in charcoal. When she eventually died, in the first decade of the nineteenth century, it was found that her room was decorated with the images of the hundreds of people she had happily sent to their deaths.

Lady Betty's cold-hearted actions meant that she was universally feared, loathed, hated and shunned. In 1802 she received a pardon for her own horrific crime. By the time of her death in 1807 a powerful myth had built up around her. It would be many years before mothers stopped threatening their children to watch out, if they didn't behave Lady Betty would get them. She is buried inside the walls of Roscommon jail, the scene of her hideous handiwork.

B

IDDY

E

ARLY

(1798-1874)

COUNTY CLARE

O

ne of the greatest gifts the fairy folk can give you is healer powers. This has featured in folklore for generations. Along with the gift of healing came the knowledge of herbs. In Ireland we call these people âfairy doctors'. One of the most famous of these was Biddy Early. We will hear more about her later on.