Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (108 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

Another ominous feature of the conflicts of 1919 was the deepening

dependence of the new political leadership on a military establishment whose enthusiasm for the emerging German Republic was questionable, to say the least. Exactly how questionable became clear in January 1920, when a number of senior officers refused outright to implement the military stipulations of the Versailles Treaty. Heading the rebellion was none other than General Walther Freiherr von Lüttwitz, who had commanded the troops engaged in the repressions of January and March in Berlin. When Army Minister Noske ordered him to disband the elite Marine Brigade under Captain Hermann Ehrhardt, Lüttwitz refused outright, called for new elections and demanded that he be placed in command of the entire German army. Here was yet another example of that spirit of egotistical insubordination that had been gaining ground within the old-Prussian military leadership since Hindenburg and Ludendorff had held the government to ransom during the First World War.

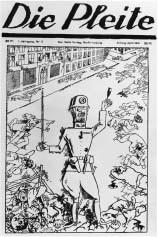

54. ‘Cheers Noske! The proletariat is disarmed!’ Drawing for the leftist satirical journal

Die Pleite

by George Grosz, April 1919.

On 10 March 1920, Lüttwitz was finally dismissed from active service; two days later he launched a putsch against the government in collaboration

with the conservative ultra-nationalist activist Wolfgang Kapp, a political intriguer who had been involved in the fall of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg in 1917. The aim was to unseat the republican government and establish an autocratic military regime. On 13 March, Lüttwitz and the Ehrhardt Brigade took control of the capital, forcing the government to flee, first to Dresden and then to Stuttgart. Kapp appointed himself Reich chancellor and minister-president of Prussia and Lüttwitz minister of the army and supreme commander of the armed forces. It looked for a moment as if the history of the young republic was already at an end. In the event, the Kapp–Lüttwitz putsch collapsed after only four days – it had been poorly planned and the would-be dictators had no means of dealing with an SPD-sponsored general strike that paralysed German industry and parts of the civil service. Kapp announced his ‘resignation’ on 17 March and quickly slipped off to Sweden; Lüttwitz resigned on the same evening and later resurfaced in Austria.

The problem of the army and its relationship with the republican authority did not disappear after the failure of the Kapp–Lüttwitz putsch. The chief of the army command from March 1920 was Hans von Seeckt, a Prussian career staff officer from Schleswig-Holstein, who initially refused to oppose Kapp and Lüttwitz, but ostentatiously sided with the government once they had failed. Under his shrewd leadership, the military command focused on building German military strength within the narrow parameters imposed by Versailles and abstained from conspicuous political interventions. Yet the army remained in many respects a foreign body within the fabric of the republic. Its loyalty was not to the existing political authority, but ‘to that permanent and imperishable entity’, the German Reich.

25

In an essay published in 1928, Seeckt set out his views on the status of the military within a republican state. He acknowledged that the ‘supreme leadership of the state’ must control the army, but also insisted that ‘the army has the right to demand that its share in the life and the being of the state be given full consideration’–whatever

that

meant!

Seeckt’s expansive conception of the army’s status found expression in his claim that ‘in domestic and foreign policy the military interests represented in the army must be given full consideration’ and that the ‘particular way of life’ of the military must be respected. Even more telling was his observation that the army was subordinate only ‘to the

state as a whole’ and not ‘to separate parts of the state organization’. The question of who or what exactly embodied the totality of the state remained unresolved, though it is tempting to read these words as encoded articulations of a crypto-monarchism in which allegiance was ultimately focused not on the state, but on the empty throne of the departed Emperor-king. This was, in other words, an army whose legitimacy derived from something outside the existing political order and whose commitment to upholding that order remained conditional.

26

Here was a potentially troublesome legacy of the Prussian constitutional tradition, in which the army had sworn its fealty to the monarch and led an existence apart from the structures of civil authority.

It was as if reality had been turned inside out. The Prussian state had passed through the looking glass of defeat and revolution to emerge with the polarities of its political system in reverse. This was a mirror-world in which Social Democrat ministers despatched troops to put down strikes by leftist workers. A new political elite emerged; former apprentice locksmiths, office clerks and basket-weavers sat behind Prussian ministerial desks. In the new Prussia, according to the Prussian constitution of 30 November 1920, sovereignty rested with ‘the entirety of the people’. The Prussian parliament was no longer convened and dissolved by a higher authority, but summoned itself under rules set out in the constitution. By contrast with the Weimar (national) constitution, which concentrated formidable powers in the person of the Reich president, the Prussian system made do without a president. It was in this sense a more thoroughly democratic and less authoritarian system than the Weimar Republic itself. Throughout the years 1920–32(with a few very brief interruptions), an SPD-led republican coalition consisting of Social Democrats, Centre Party deputies, left-liberals (DDP) and – later – right-liberals (DVP) governed with a majority in the Prussian Landtag. Prussia became the ‘rock of democracy’ in Germany and the chief bastion of political stability within the Weimar Republic. Whereas Weimar politics at the national level were marked by extremism, conflict and the rapid alternation of governments, the Prussian grand coalition held firm and steered a steady course of moderate reform. Whereas the German

national parliaments of the Weimar era were periodically cut short by political crises and dissolutions, every one of their Prussian counterparts (except the last) was allowed to live out its full natural lifespan.

Presiding over this surprisingly stable political system was Prussia’s ‘red Tsar’, Minister-President Otto Braun. The son of a railway clerk in Königsberg, Braun had been trained in his youth as a lithographer, joined the SPD at the age of sixteen in 1888 and soon became well known as a leader of the socialist movement among rural East Prussian labourers. He became a member of the party’s executive council in 1911 and joined the small contingent of SPD deputies in the lower house of the old Prussian Landtag two years later. His sobriety, pragmatism and moderation helped to create a framework for harmonious government in Germany’s largest federal territory. Like many other Social Democrats of his generation, Braun professed a deep attachment to Prussia and a respect for the intrinsic virtue and authority of the Prussian state – an attitude shared to some extent by all the coalition partners. Even the Centre Party made its peace with the state that had once so energetically persecuted Catholics; the high point of their rapprochement was the concordat agreed between the Prussian state and the Vatican on 14 June 1929.

27

In 1932, Braun could look back with a certain satisfaction on what had been achieved since the end of the First World War. ‘In twelve years,’ he declared in an article for the SPD newspaper

Volksbanner

in 1932, ‘Prussia, once the state of the crassest class domination and political deprivation of the working classes, the state of the centuries-old feudal Junker caste hegemony, has been transformed into a republican people’s state.’

28

But how deep was the transformation? How profoundly did the new political elite penetrate the fabric of the old Prussian state? The answer depends upon where one looks. If we focus on the judiciary, the achievement of the new power-holders looks unimpressive. There were certainly piecemeal improvements in discrete areas – prison reform, industrial arbitration and administrative rationalization – but little was done to consolidate a pro-republican ethos among the upper ranks of the judicial bureaucracy and particularly among the judges, who tended to remain sceptical of the legitimacy of the new order. Many judges mourned the loss of king and crown – in a famous outburst of 1919, the head of the League of German Judges declared that ‘all majesty lies prostrate, including the majesty of the law.’ It was common knowledge that many

judges were biased against left-wing political offenders and prone to look more leniently on the crimes of right-wing extremists.

29

The key impediment to radical action by the state in this area was a deeply embedded respect – especially among the liberal and Centre Party coalition partners – for the functional and personal independence of the judge. The autonomy of the judge – his freedom from political reprisals and manipulation – was seen as crucial to the integrity of the judicial process. Once this principle was enshrined in the Prussian constitution of 1920, a thorough-going purge of anti-republican elements in the judiciary became impossible. Changes to the appointments procedures for new judges promised future improvement, as did the setting of a compulsory retirement age, but the system inaugurated in 1920 did not last long enough to allow these adjustments to take effect. A senator of the Supreme Court in Berlin estimated in 1932 that perhaps 5 per cent of the judges sitting on the Prussian bench could be described as supporters of the republic.

The SPD-led government also inherited a civil service that had been socialized, schooled, recruited and trained in the imperial era and whose allegiance to the republic was correspondingly weak. Just how weak was revealed in March 1920, when many provincial and district governors continued working in their offices during the Kapp–Lüttwitz putsch and thus implicitly accepted the authority of the would-be usurpers. The situation was most acute in the province of East Prussia, where the entire senior bureaucracy recognized the Kapp–Lüttwitz ‘government’.

30

The first office-holder to tackle this problem with the required energy was the new Social Democrat Interior Minister Carl Severing, a former locksmith from Bielefeld, who had risen through the ranks of the SPD as a journalist-editor and sometime Reichstag deputy. Under the ‘Severing system’, grossly compromised individuals were dismissed and representatives of the governing parties vetted all new appointees to ‘political’ (i.e. senior) civil service posts. It was not long before this practice had a marked effect on the political complexion of the senior echelons. By 1929, 291 of the 540 political civil servants in Prussia were members of the solidly republican coalition parties SPD, Centre and DDP. Nine of the eleven provincial governors and 21 of the 32 district governors belonged to the coalition parties. The social composition of the political elite was transformed in the process: whereas eleven out of twelve provincial governors had been noblemen in 1918, only two of the men

who served in this post over the years 1920–32 were of noble descent. That this transition could be effected without disrupting the operations of the state was a remarkable achievement.

Policing was another area of crucial importance. The Prussian police force was far and away the largest in the country. Here too, there were nagging doubts about political loyalty, especially after the Kapp–Lüttwitz putsch, when the Prussian police administration failed unequivocally to declare its allegiance to the government. On 30 March 1920, only two weeks after the collapse of the putsch, Otto Braun announced that he intended to institute a ‘root and branch transformation’ of the Prussian security organs.

31

Personnel reform in this area was not particularly problematic, since control over appointments lay entirely in the hands of the interior ministry, which, with one brief break, remained under SPD control until 1932. Responsibility for overseeing personnel policy fell to the decidedly republican head of the police department (from 1923) Wilhelm Abegg, who saw to it that adherents of the republican parties were appointed to all key posts. By the late 1920s, the upper echelons of the police force had been comprehensively republicanized – of thirty Prussian police presidents on 1 January 1928, fifteen were Social Democrats, five belonged to the Centre, four were German Democrats (DDP) and three were members of the German People’s Party; the remaining three declared no political affiliation. It was official policy throughout the police service to base recruitment not only upon mental and physical aptitude, but also upon the candidate’s having a record of ‘past behaviour guaranteeing that they would work in a positive sense for the state’.

32

Yet doubts remained about the political reliability of the police force. The great majority of officers and men were former military men who brought military manners and attitudes with them into the service. Among senior police cadres, there was still a strong old-Prussian reserve officer element with informal links to various right-wing organizations. The mood in most police units was anti-Communist and conservative, rather than specifically republican. They saw the enemies of the state on the left – including the left wing of the SPD, the party of government! – rather than among the extremists on the right, whom they viewed with indulgence if not sympathy. A police officer who openly proclaimed his pro-republican allegiance was likely to remain an outsider. The Centre Party functionary Marcus Heimannsberg was a man of modest social

origin who rose swiftly through the ranks under the protection of SPD Interior Minister Carl Severing. But he was widely resented among his fellow senior officers as a political appointment and remained socially isolated. Others who were less protected suffered the discrimination of their colleagues and risked being passed over for promotion. In many locations, policemen of known republican sentiment were ostracized from the gregarious – and professionally important – after-hours sociability of the regulars’ table at the local pub.

33