Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (58 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

‘The abolition of serfdom has consistently been my goal since the beginning of my reign,’ Frederick William III told two of his officials shortly after the Peace of Tilsit. ‘I desired to attain it gradually, but the unhappy condition of our country now justifies and indeed demands speedier action.’

32

Here again, the Napoleonic shock was the catalyst, not the cause. The ‘feudal’ system of land tenures had long been under growing pressure. Some of it was ideological, and resulted from the percolation of physiocratic and Smithian liberal ideas into the Prussian administration. But the economic rationale for the old system was also wearing

thin. The growing use of waged employees, who were plentiful and cheap in an era of demographic growth, emancipated many estate owners from dependence on the labour services of subject peasants.

33

Moreover, the late eighteenth-century boom in grain prices produced new imbalances within the system. The better-endowed peasants took their grain surpluses to market and rode the boom while paying wage-labourers to perform their ‘feudal’ services for them. Under these conditions, the existence of a large subject peasantry whose secure land tenures were paid for with labour rents came to seem economically counterproductive. Labour dues, once a highly valued attribute of Junker manorial governance, now functioned like fixed rents within a system that benefited the better endowed peasants as ‘protected tenants’.

34

Two Stein associates, Theodor von Schön and Friedrich von Schroetter, were entrusted with the task of preparing a draft law outlining reforms to the agrarian system. The result was the edict of 9 October 1807, sometimes called the October Edict, the first and most famous of the legislative monuments of the reform era. Like so many of the reform decrees, it was more a declaration of intentions than a law as such. The edict heralded fundamental changes to the constitution of Prussian rural society, but there was a bombastic vagueness about many of its formulations. Essentially, it aimed to achieve two objectives. The first was the liberation of latent economic energies – the preamble declared that every individual should be free to achieve ‘as much prosperity as his abilities allow’. The second was the creation of a society in which all Prussians were ‘citizens of the state’ equal before the law. These objectives were to be achieved through three specific measures. First, all restrictions on the purchase of noble land were abandoned. The state at last gave up its futile struggle to maintain the noble monopoly in privileged land and created for the first time something approximating a free land market. Second, all occupations were henceforth to be open to persons of all classes. For the first time there was to be a free market in labour, untrammelled by guild and corporate occupational restrictions. This too was a measure with a long prehistory: since the early 1790s, the abolition of guild controls had been the subject of repeated discussions between the General Directory and the Factory Department in Berlin.

35

Thirdly, all hereditary servitude was abolished – in a hugely suggestive but tantalizingly imprecise formulation, the edict announced

that ‘from Saint Martin’s Day [11 November] 1810, there will only be free people’ in the Kingdom of Prussia.

This last stipulation sent an electric shock through the rural communities of the kingdom. It also left many questions open. The peasants were to be officially ‘free’ – did this mean they were no longer obliged to perform their labour services? The answer was less obvious than it might seem, since most labour services were not attributes of personal servitude but forms of rent payable for land tenure. Nevertheless, landlords in many districts where the edict became common knowledge found it virtually impossible to persuade the peasants to perform their services. Efforts by the authorities in Silesia to prevent the news from reaching the villages failed, and in the summer of 1808 a rebellion broke out among peasants who believed they were now being held in unlawful subjection.

36

A further vexing question was that of the ultimate ownership of peasant land. Since the edict made no reference to the principle of peasant protection that had traditionally informed Prussian agrarian policy, some noble landlords regarded it as a carte blanche for the seizure – or reclamation, as they saw it – of land under peasant cultivation, and there were a number of wildcat appropriations. A degree of clarity was achieved through the Ordinance of 14 February 1808, which stated that the ownership of land depended on the prior conditions of tenure. Peasants with strong ownership rights were secure against unilateral appropriation. Those with temporary leases of various kinds were in a weaker position; their lands could be appropriated, though only with the permission of the authorities. But many details of interpretation were still contested and it was only in 1816 that the questions of land ownership and the compensation of landlords for the services and land they had lost were settled.

The final position, as set out in the Regulation Edict of 1811 and the Declaration of 1816, defined a range of hierarchically graded prior peasant tenures and allotted them correspondingly differentiated rights. Broadly speaking, there were two options. The land could be partitioned, in which case peasants with hereditary tenures retained use rights to two-thirds of the land they had traditionally worked (one-half in the case of non-hereditary tenures), or the peasant might buy it outright, in which case the seigneurial portion had to be paid off. The payment of

compensation by peasants for land, services and natural rents dragged on in many cases for over half a century. Peasants at the bottom end of the range were not entitled to convert the land they worked to freehold titles and their lands were vulnerable to enclosure.

37

These measures were in tune with then fashionable late-enlightenment physiocratic doctrine that freeing peasants from labour dues and other irksome ‘feudal’ duties ought to make them more productive. And the writings of Adam Smith, whose works were held in high esteem among the younger cohorts of the Prussian bureaucracy (including Schroetter and Schön), suggested that it might be best to let the weakest of the peasants lose their land, since they would in any case be unviable as independent farmers.

38

Some noblemen resented bitterly this tampering with the agrarian constitution of old Prussia. For the conservative neo-Pietists around the Gerlach brothers in Berlin the years of reform brought the realization that the monarchical state posed as potent a threat to traditional life as the revolution itself. The growing pretensions of the central bureaucracy, Leopold von Gerlach believed, supplemented the personal power of the monarch with a new ‘administrative despotism that eats away at everything like vermin’.

39

The most trenchant and memorable spokesman for this point of view was Friedrich August Ludwig von der Marwitz, an estate owner at Friedersdorf near Küstrin on the edge of the Oder floodplain, who denounced the reforms as an assault on the traditional patriarchal structure of the countryside. Hereditary subject-hood, he argued, was not a residue of slavery, but the expression of a familial bond that joined the peasant to the nobleman. To dissolve this bond would be to undermine the cohesion of the society as a whole. Marwitz was a melancholy character to whom nostalgia came naturally; he articulated his reactionary views with great intelligence and rhetorical skill, but he remained an isolated figure. Most noblemen saw the advantages of the new dispensation, which gave relatively little to most peasants and allowed the estate owner to intensify the agrarian production process using cheap wage labour on land unencumbered by complex hereditary tenures.

40

By scouring the legal residue of ‘feudalism’ from the noble estates, the October Edict aimed to facilitate the emergence of a more politically cohesive society in Prussia. ‘Subjects’ were to be refashioned into ‘citizens of the state’. Yet the reformers understood that more positive measures would be needed to mobilize the patriotic commitment of the population. ‘All our efforts are in vain,’ Karl von Altenstein wrote to Hardenberg in 1807, ‘if the system of education is against us, if it sends half-hearted officials into state service and brings forth lethargic citizens.’

41

Administrative and legal innovations alone were insufficient; they had to be sustained by a broad programme of educational reform aimed at energizing Prussia’s emancipated citizenry for the tasks that lay ahead.

The man entrusted with renewing the kingdom’s educational system was Wilhelm von Humboldt, descendant of a Pomeranian military family who had grown up in the enlightened Berlin of the 1770s and 1780s. His tutors had included the emancipationist Christian Wilhelm von Dohm and the progressive jurist Ernst Ferdinand Klein. On the urging of Stein, Humboldt was appointed director of the Section for Religion and Public Instruction within the interior ministry on 20 February 1809. He was something of an odd-man-out among the senior reformers. He was not by nature a politician, but a scholar of cosmopolitan temperament who had chosen to spend much of his adult life abroad. In 1806, Humboldt was living with his family in Rome, hard at work on a translation of Aeschylus’s

Agamemnon

. Only after the collapse of Prussia and the plundering by French troops of the Humboldt family residence in Tegel to the north of Berlin did he resolve to return to his beleaguered homeland. It was only with great reluctance that he agreed to accept a post in the new administration.

42

Once installed, however, Humboldt unfolded a profoundly liberal reform programme that transformed education in Prussia. For the first time, the kingdom acquired a single, standardized system of public instruction attuned to the latest trends in progressive European pedagogy. Education as such, Humboldt declared, was henceforth to be decoupled from the idea of technical or vocational training. Its purpose was not to turn cobblers’ boys into cobblers, but to turn ‘children into

people’. The reformed schools were not merely to induct pupils into a specific subject matter, but to instil in them the capacity to think and learn for themselves. ‘The pupil is mature,’ he wrote, ‘when he has learned enough from others to be in a position to learn for himself.’

43

In order to ensure that this approach percolated through the system, Humboldt established new teachers’ colleges to train candidates for the kingdom’s chaotic primary schools. He imposed a standardized regime of state examinations and inspections and created a special department within the ministry to oversee the design of curricula, textbooks and learning aids.

30

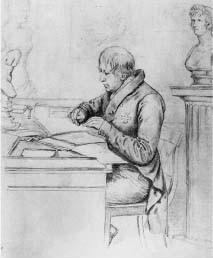

. Wilhelm von Humboldt,

drawing by Luise Henry, 1826

The centrepiece – and most enduring monument – of the Humboldt reforms was the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität founded in Berlin in 1810 and installed in the vacated palace of Prince Henry, the younger

brother of Frederick the Great, on Unter den Linden. Here too, Humboldt strove to realize his Kantian vision of education as a process of self-emancipation by autonomous, rational individuals.

Just as primary instruction makes the teacher possible, so he renders himself dispensable through schooling at the secondary level. The university teacher is thus no longer a teacher and the student is no longer a pupil. Instead the student conducts research on his own behalf and the professor supervises his research and supports him in it. Because learning at university level places the student in a position to apprehend the unity of scholarly enquiry and thereby lays claim to his creative powers.

44

From this it followed that academic research was an activity with no predetermined end-point, no objective that could be defined in purely utilitarian terms. It was a process whose unfolding was driven by an immanent dynamic. It was concerned less with knowledge in the sense of accumulated facts than with reflection and reasoned argument. This was homage to the pluralist scepticism of Kant’s critique of human reason, and also a return to that vision of an all-embracing conversation that had animated Prussia’s enlightenment. Essential to the success of this enterprise was that it should be free from political interference. The state should abstain from intervening in the intellectual life of the university, except as a ‘guarantor of liberty’ in cases where a dominant clique of professors threatened to suppress academic pluralism within their own ranks.

45

The Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (renamed Humboldt-Universität in 1949) quickly secured pre-eminence among the universities of the Protestant German states. Like the University of Halle in the age of the Great Elector, the new institution served to broadcast the cultural authority of the Prussian state. Indeed its foundation was partly motivated by the need to replace Halle, which had been lost to the Prussian Crown in the territorial settlement imposed by Napoleon. In this sense, the new university helped, as Frederick William III put it, to ‘replace by intellectual means what the state had lost in physical strength’. But it also – and herein lies its true significance – lent institutional expression to a new understanding of the purpose of higher education.