Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (7 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

By the turn of the twentieth century, a distinct society was well established in Chagos. The population neared 1,000 and there were six villages on Diego Garcia alone, served by a hospital on each arm of the atoll. While conditions varied to some extent from island to island and from administrator to administrator within each island group, growing similarities became the rule. Chagos Kreol, a language related to the Kreols in Mauritius and the Seychelles, emerged among the islanders.

39

People born in Chagos became collectively known by the Kreol name

Ilois

.

*

40

Most considered themselves Roman Catholic—a chapel was built at East Point in 1895, followed by a church and chapels on other islands—although religious and spiritual practices and beliefs of African, Malagasy, and Indian origins remain present to this day. A distinct

“culture des îles

”—culture of the islands—had developed, fostered by the islands’ isolation. “It is a system peculiar to the Lesser Dependencies,” Scott would later write, “and it may be fairly described as indigenous and spontaneous in its emergence.”

41

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 1.2 View of East Point village, Diego Garcia, from the lagoon, 1968. Photo courtesy of Kirby Crawford.

KUTO DEKOKE

Most mornings, Rita rose for work at 4 a.m. “At four o’clock in the morning, I got up. I made tea for the children, cleaned the house everywhere. At seven o’clock I went for the call to work.”

Each morning, she said, the manager gave work orders to the commandeurs, who delivered them to other Chagossians. There were many jobs: cleaning the camp, cutting straw for the houses, harvesting the coconuts, drying the coconuts, work for the manager and his assistant, work at the hospital, child care. Most men worked picking coconuts, 500 or more a day, removing the fibrous husk with the help of a long, spearlike

pike dekoke

knife, planted in the ground. This left the small hard nut within the coconut, which others transported to the factory center. There, like most other women, Rita shelled the interior nut, digging the flesh out with a specialized coconut-shelling knife, the

kuto dekoke

.

“I put it on the ground. I hit it. It splits. I have my knife. I scoop it in quickly, and I dump it over there: the shell on one side, the coconut flesh on the other,” Rita explained.

Often she would complete the day’s task of shelling 1,200 coconuts by 10:00 or 10:30 in the morning—meaning a rate of about one nut every 10 seconds. The women sat in groups, children often at their sides, amid hills of coconuts, cracked emptied shells, and bright white coconut flesh. Their hands were a concentrated swirl of movement—picking the nut, hitting it once, scoop, scoop with the knife between the flesh and the shell, flesh flying in one direction, empty shell in another. And again, pick, hit, scoop, scoop, flesh, flesh, shell. And again, pick, hit, scoop, scoop, flesh, flesh, shell. And again.

“Then there are other people who take the flesh,” Rita said, “to dry it” in the sun. “When it’s dry, they gather it up and put it in the

kalorifer

,” a heated shed fueled by burning coconut husks. There the flesh was fully dried, producing copra to make oil. Some of the copra was crushed on the spot in a donkey-powered oil mill. Most, Rita explained, went “to Mauritius—was sent all over.”

42

“THINGS WILL BE OVERTURNED”

On a seemingly ordinary Monday morning in August 1931, when Rita Bancoult was ten, Peros Banhos commandeur Oscar Hilaire gave his usual work orders to fifteen Chagossian men to go to Petit Baie island for a week to gather and husk 3,000 coconuts each. The fifteen refused the order.

43

Two days later they finally left for Petit Baie, but returned the same day, refusing to work any further. For the remainder of the week, the men went on strike and didn’t report to work.

The following Saturday, nine islanders confronted the assistant manager, Monsieur Dagorne, about the size of a task of weeding he was giving some women. Two days later, a group again confronted Dagorne and demanded that he reduce the women’s tasks. This time he complied.

A few hours later, according to a police magistrate’s eventual report, one woman assaulted another “for having advised her fellow workers . . . to obey the orders of the staff and to refuse to obey those who wished to create a disorder on the estate.” When the victim went to complain to the head manager, Jean Baptiste Adam, a crowd followed, yelling “threatening language” at Adam.

44

The crowd then turned and hurried into the kalorifer. There they ripped from the wall a rod, the length of a French fathom, used to measure lengths

of rope made by elderly, infirm women working from their homes and paid by the length. They rushed back to Monsieur Adam with the rod and protested that it was a “false measure.”

45

Moments later they returned to the kalorifer and placed a new measure on the wall—this one about 8 French inches shorter.

The next morning, the same group showed up at the center of the plantation and told the women to stop shelling coconuts. The group threatened to stop all work if Monsieur Adam did not add an extra laborer to the workforce at the kalorifer. The manager agreed to the change. Later they forced him to reduce the women’s weeding and cleaning tasks, and still, all but two of the women walked off the job. The men told the manager they would refuse to unload and load the next cargo ship to arrive at Peros unless he and Dagorne were on the ship when it returned to Mauritius.

The insurgency continued into September. “Adam had lost all authority over these men,” the police magistrate later reported. After a Chagossian drowned to death while sailing from Corner Island to another islet to collect coconuts, his partner and a crowd of supporters entered the manager’s office, barred the exits, and forced him to sign a document granting her a widow’s pension. They also forced him to give her free coffee, candles, sugar, and other goods from the company store to observe the islanders’ traditional mourning rites.

46

Over the next two weeks, leaders of the insurgency twice made Dagorne buy them extra wine from the company store. One leader, Etienne Labiche, again protested the task assigned to some women. “You are going on again because I am remaining quiet,” Labiche challenged the managers in Chagos Kreol, according to the police magistrate. “We shall see when the boat arrives.

Sa boule-la pour devirer

.” Things will be overturned. Within minutes of issuing the challenge, the islanders had left work for the day. Days later Labiche and some supporters forced Dagorne to reveal that he was living with a mistress. Adam suspended Dagorne on the spot for “scandalous conduct.”

47

Labor unrest continued into a second month, with Labiche, Willy Christophe, and others forcing the manager to lower the price of soap at the company store when they suspected price gouging and Adam was unable to show them a price invoice. During the protest a few approached the store’s back door. The island’s pharmacist pulled out a revolver and “threatened to blow out the brains of the first man who tried to enter the shop.”

48

When two weeks later the cargo ship

Diego

finally came within sight on its voyage from Mauritius, the blast of a conch shell reverberated through the air as a signal among the islanders. Manager Adam went aboard the

ship and returned to shore minutes later with his brother, the captain of the

Diego

. “The whole of the population met them at the landing stage,” the magistrate’s report recounts, “uttering loud shouts, and demanding to see the invoice” listing the prices for articles sold at the shop. The crowd accompanied Adam and his brother to the manager’s house “shouting and threatening, climbed up the balcony stairs, and even into his dining room.” There Adam unsealed the invoice. Someone in the crowd looked over Adam’s shoulder and read the prices aloud. “Having noticed a mention in the official letter about a case of tobacco (plug) and the rise in the price . . . the crowd demanded the return of the case to Mauritius.”

49

At the next morning’s call for work, none of the men appeared. When the captain of the

Diego

asked them why they were not coming to work, they told him they would only work if his brother and Dagorne were sent back to Mauritius. A standoff ensued. The ship eventually left with its cargo aboard, but with Manager Adam and Dagorne still in Peros.

Three months and two days after the beginning of the insurgency, Mauritian magistrate W. J. Hanning arrived in the atoll along with an armed guard of ten police constables, two police inspectors, and two noncommissioned officers. Hanning and Police Inspector Fitzgibbon charged, convicted, and sentenced 36 Chagossian men and women for offenses including “larceny soap,” “larceny rope measure,” “extortion of document,” “coalition to prevent unloading cargo,” and “coalition to prevent work.” Two were convicted of “wounds & blows.” Punishment for the charges of larceny and extortion ranged from three to twelve months’ hard labor. Labiche received a total of 30 months’ hard labor; others got up to 36 months. Hanning sent three commandeurs back to Mauritius and mandated the reading of the names of the convicted and their punishments throughout the rest of Chagos and the other Mauritian dependencies.

50

“I have the honour to state that quiet has been restored at Peros,” Magistrate Hanning wrote. Although he thought the insurgents’ grievances “imaginary” and found the islanders “economically many times better off than the Mauritian labourer,” he concluded his report by calling on the plantation owners to “exercise some leniency” over markups on prices for “articles of necessity” sold at the company store.

51

GROWING CONNECTIONS

In 1935, new owners in Chagos established the first regular steamship connection between Mauritius and Chagos after completing the consolidation

of ownership over the various plantations, which had begun in the 1880s. Previously the islands sent copra, oil, and other goods to Mauritius and received supplies on twice-a-year boats. The new four-times-a-year steamship system decreased travel times significantly and provided a regular connection between Diego Garcia and the northern islands of Peros Banhos and Salomon, over 100 nautical miles away. Peros to Salomon transportation was by sailing ship and later motorboat. Transportation within each group and around Diego Garcia’s lagoon was generally by small, locally built sailboats, and later by motorboats. News from the outside world came primarily from illustrated magazines and other reading materials supplied by the transport vessels visiting Chagos.

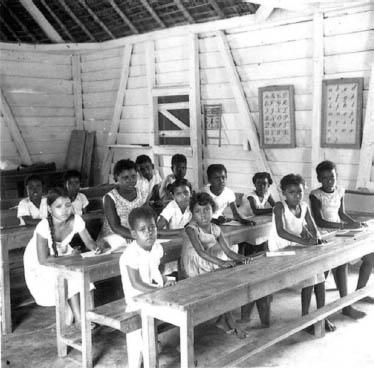

Figure 1.3 Schoolchildren in Chagos, 1964. Photographer unknown.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Chagos had been so isolated that at the start of World War I, management on Diego Garcia supplied the German battleship

Emden

with provisions before learning that Britain and its colonies were already at war with Germany. By contrast, thirty years later during World War II, Diego Garcia became a small landing strip for Royal Air Force reconnaissance aircraft and a base for a small contingent of Indian Army troops. At war’s end, the troops went home, leaving behind a wrecked Catalina seaplane that became a favorite playground for children.

By the mid-twentieth century, Chagos had moved from relative isolation to increasing connections with Mauritius, other islands in the Indian Ocean, and the rest of the world. Copra and coconut oil exports were sold in Mauritius and the Seychelles, and through them in Europe, South Africa, India, and Israel. Wireless communications at local meteorological stations connected the main islands with Mauritius and the Seychelles. Shortwave radios allowed reception of broadcasts from at least as far as the Seychelles and Sri Lanka.

52

The Mauritian colonial government started showing increasing interest in the welfare of Chagos’s inhabitants and its economy. Specialists sent by the government investigated health and agricultural conditions. With the help of their reports, the government established nurseries in each island group, schools, and a regular garbage and refuse removal system reported to be better than that in rural Mauritius.

53

Water came from wells and from rain catchment tanks. Small dirt roads traversed the main islands, and there were a handful of motorbikes, trucks, jeeps, and tractors.

“NOTHING WE HAD TO BUY”

By the 1960s, everyone in Chagos was guaranteed work on the plantations and pensions upon retirement.

54

The vast majority of Chagossians still worked as coconut laborers. A few male laborers rose to become foremen and commandeurs, and a few women were also commandeurs. Other men became artisans working as blacksmiths, bakers, carpenters, masons, mechanics, and in other specialized positions.