Read It Was the Nightingale Online

Authors: Henry Williamson

It Was the Nightingale (6 page)

“Oh, I’m not a business man, George. How’s journalism going?”

“I’ve got a good idea for an article on bell-ringing, which ought to go well at the New Year! I used to be a ‘colt’, ringing with the team at the old pater’s church. My idea is to have six copies of the same article made, then send them out just after Christmas, to six papers. One of them is sure to take it, and it will save time sending the same article back and forth, and so missing the ’bus.”

The talk came round to spiritualism; an argument developed and continued on the sands: Phillip in sympathy with Bob, who was devout in his beliefs in life after death and in the power of spiritual healing; George deriding what both said.

“Yes,

you

believe in it, I don’t doubt that for a moment, old bean, but what proof have you got? The old pater knows a lot of rogues in his parish, some of them pretend to believe in spiritualism only to get money out of a number of war-widows who haven’t been able to get another husband. You ought to hear the old pater on the subject! He doesn’t believe a word of it, and says it’s against the teachings of Holy Writ.”

“I’m not saying that there aren’t any f-f—frauds, but I have p-proved that the dead can m-m-materialise,” stuttered Bob.

“Belief is a matter of sensibility,” said Phillip. “‘The fool sees not the same tree that the wise man sees’, as William Blake wrote.”

“Nor does the fool see the same tree that the dog sees!” chortled George.

The upshot was that Phillip proposed a test.

“Let’s have a

séance

tonight in my cottage, and Bob shall show us what he thinks are manifestations.”

“Why not in my place?” said George. “Then we can combine it with sampling my whit-ale! It’s just mature, and I can guarantee a more substantial kind of spirits if the other kind doesn’t turn up!”

The Pole-Cripps’ came over after supper, Georgie waving a catalogue.

His enthusiasm was now for a Home Knitting Machine, on which his wife could knit a combination of golosh and stocking to go over a lady’s shoes to prevent cold feet when being driven in winter in an open car. He would breed Angoras, and Boo would turn them into overboots!

A cold mist had drifted in from the sea, so Phillip lit the driftwood on the hearth. Young Maundy, heir to possible millions via the Lloyd George Election Fund, lay asleep in his wicker cradle on one side of the hearth. In another basket on the farther side lay Rusty, Lutra, Moggy, and the tail of a mouse she had brought in for her foster-child from whose joyous embraces she was ever ready to escape by leaping on table, book stand, and if necessary up trees. But now, filled with herrings, Lutra slept on his back, legs in air and Moggy across his neck, while Rusty groaned underneath.

“Half a jiffy, before we start,” said George. “I’ll just dash down to my place to see if I’ve left the fire-guard in front of the fire.”

“We made up a good fire, hoping that you will all come over afterwards and take coffee with us, and crab sandwiches,” said Boo.

“Don’t forget the whit-ale!” called out Georgie from the open door.

“We mustn’t be late,” said Doris. “We plan to make an early start tomorrow, it’s such a long way back to Romford.” She sat with impassive face on the settle.

When George returned they sat round the table. A single candle burned on the book-stand against the wall. Phillip put on a record of Debussy’s

La

Mer.

When it stopped he got up, lifted off the sound box, and sat down again quietly.

Bob Willoughby was staring at the table. He drew a deep breath, stretched his arms before him, and rested his finger-tips

on the wood. He drew another deep breath and closed his eyes. His body moved back from his arms, which were now taut. His fingers opened, quiveringly. He passed a hand across his face several times before lowering his chin on his chest.

Looking across to George, Phillip saw on his face a childish astonishment. Glancing at Boo next, he saw the same look. Her eyes were upon the medium, and following her gaze he saw that Bob’s face was altered. The cheeks were fuller, it seemed that hair had grown on the bare patches above his temples, and the back of his hair, close cut and usually upright, was curly. Was he imagining that Bob now looked like Percy Pickering? Cold shivers passed across his shoulder blades.

“Does anyone notice anything?” whispered Boo.

“I do. His face is altogether different!” said George.

“Others have seen me, too,” said Bob, slowly and without stutter. “I am asking to come through you, my friend.”

Phillip looked at his sister. She sat with eyes closed, hands folded as though in resignation. The medium gave a deep sigh, and stroked his temples horizontally with long, stiff fingers. His face was haggard.

“Please listen to me,” a voice said faintly. “Please talk to me.”

Was it Bob’s voice? George looked at Phillip. “Do you know who it is?” he whispered.

Phillip put finger to lips.

“Speak to me,” came the words from Bob, as though half-strangled. His hands were shaking. His head went to one side; he sighed deeply, twice, then opened his eyes. With arms now limp on the table he remained as though resting.

*

“How about another go?” suggested George. “After I’ve looked at my fire?”

“Yes, and with our hands on the table this time, and everyone looking up,” said Doris.

“Don’t you believe in it, Doris?” asked Boo, when George had left.

“I’d rather not say, if you don’t mind.”

Boo, surprised at the curt tone of voice, looked across to Phillip. “Do you, Phillip?”

“Well, Boo, I don’t see that the idea of vibrations of thought is any more unnatural that the idea of the human voice coming

with broadcast wireless waves. One day we may be able to pick up what people said hundreds of years ago. We might even be able to hear the voice of the central figure on the Cross.”

Bob nodded slowly to himself.

George came back, noticeably brighter, rubbing his hands together. “I say, old bean,” he said to Phillip, “you know I told you that I’d painted the Trojan’s mudguards with this new cellulose paint? I reckon it’s put fifteen miles an hour on her maximum speed. Hasn’t it, Boo?” seeking the accustomed support from his wife. “You timed me, didn’t you? I’ll tell you how we did it if you like, two days ago, coming back from Exeter. You know that straight bit between——”

“Yes, Georgie,” said Boo, as to a child, “but I rather think that perhaps the spirits want to tell us something.”

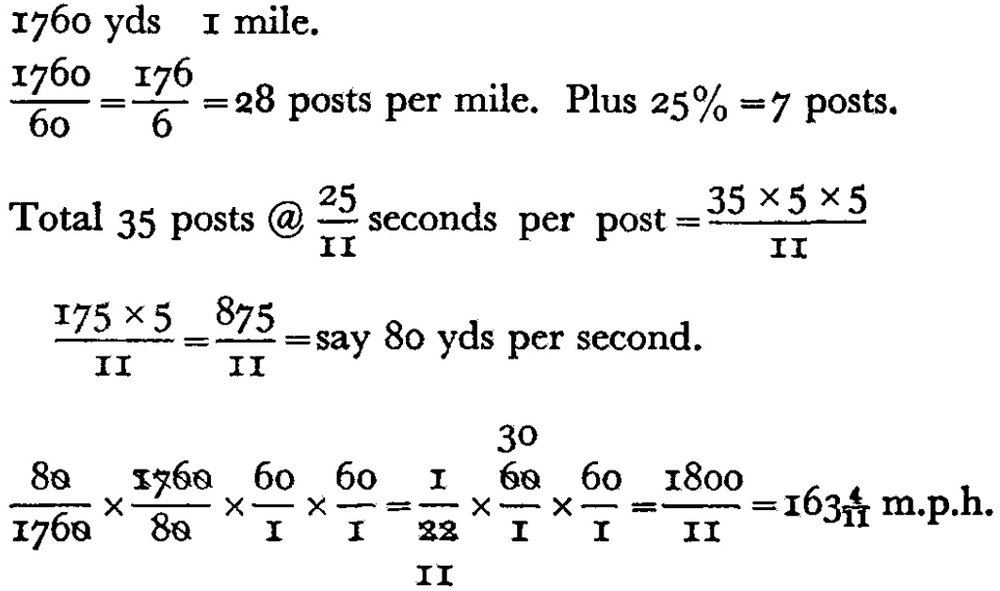

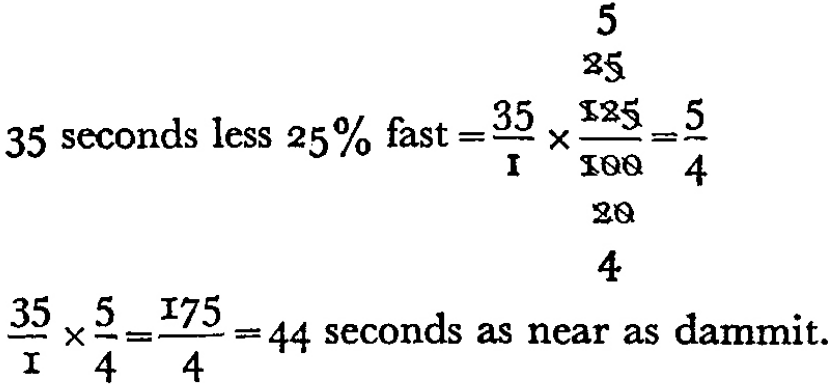

“It won’t take a minute, and might help the atmosphere. After all, life is made up of vibrations, and there was plenty in the old ’bus, ha-ha-ha, when you timed me on the straight between the telegraph posts, wasn’t there?” He turned to Phillip. “We passed eleven posts in thirty-five seconds, with the wind behind us, I must admit, and as the posts are sixty yards apart, I worked it out at eighty-two point two miles an hour! Although I must admit that Boo’s hair-spring was held up, so allow twenty-five per cent fast. I’ll show you the first set of figures. Take a look at that, old bean, and tell me what you think.”

He selected one of three sheets of paper.

“What’s this, Georgie? A message from ‘Red Cloud’?”

“Sorry old bean, I’ve given you the wrong set of figures. Here’s the right one.”

“Georgie dear, the spirits may go away if we interrupt the atmosphere.”

“Let him get it off his mind,” said Bob, quietly.

“Thanks, old bean. Now just take a dekko at this one, will you?”

“Ah, a corrected message from ‘Dust Cloud,”’ said Phillip. “I don’t know how you do it, Georgie.”

“Ah, but don’t forget the streamlined mudguards! You remember I told you that I had put on some of the new cellulose paint? Well, at first I put it on top of the old paint, and when that curled up I stripped both mudguards to the metal and after I’d painted them again with cellulose it made a tremendous difference to wind-resistance, didn’t it, Boo?”

“It certainly appeared to. Now, Georgie, we haven’t much time.”

They sang

Rock

of

Ages,

then spread their fingers round the table. Soon it began to quiver. Phillip could see the nails of

George whiten as he pressed. “Ought we to push?” he asked George.

“

I’m

not pushing! I’m trying to keep it down!”

“You’re still driving the Trojan,” laughed Phillip.

“Let it rise if it wants to, touch lightly,” said Bob between his teeth, as the table began to quiver again.

“Its legs aren’t very firm at the best of times, so keep your fingers lightly on the wood,” Phillip whispered to George.

The table began to creak.

“I know that chap you got to make this table for you, he’s a crook,” said George. “If you had come to me, I could have put you on to a decent carpenter the old pater knows.”

“Georgie dear, we weren’t so fortunate as to know Phillip then.”

“All the same, he was taken in by the chap who made this table!”

“Have you been drinking some of the whit-ale, by any chance?” asked Phillip.

“You’re avoiding the issue! You know it was a dud table!”

“Georgie, if you keep on, you’ll drive the spirits away.”

“Ha ha, I like that.”

“Please keep your finger-tips lightly on the edge of the table,” said Bob.

The table began to creak again, then to turn.

“At least you can’t accuse me of doing it this time, old bean!” said George as he lifted his hands.

The movement stopped.

“You’ve broken the circuit,” said Phillip.

“

Please,

Georgie! We’ll have to stop in a few minutes.”

The others sat still, waiting. George put his fingers on the table.

Silence followed.

“I think someone is wanting to speak to us,” said Bob in a low voice. He raised his chin, and closed his eyes. “We are ready to hear you speak. Please will you lift the table sideways and tap the leg on the floor once for a ‘no’, and twice for a ‘yes’? Will you first tell us if you are trying to speak?”

The table leg rose up about an inch, went down, and rose again. Phillip saw George’s fingers almost clawing the varnished wood towards himself. Not wanting to do the same, he held his

fingers lightly, and to his surprise the table rose up on the opposite legs.

“Thank you,” said Bob. “Will you tell us if you are an old soldier?”

The table canted twice, away from George.

“Ask a question, Phillip,” muttered Bob, who appeared to be wrestling with himself.

“Were you killed on the Somme?”

The table creaked as it canted: Phillip again felt the back of his neck turn icy. Tears stood in his eyes. He smelt again the falsely sweet, sickening smell of a summer battlefield. There was the sound of an explosion, like a distant Mills grenade. Another. A third.

“Oh, my God!” cried Boo, looking frightened. “What can it be?” There was a further muffled report.

George leapt up and ran to the window. “Our cottage is on fire!”

They went to the door and saw a rosy glow coming from the uncurtained lower window.

“It’s only the chimney!” cried Phillip, as a lilac flame pierced the darkness above the thatch. “Barley, will you and Bob get all the pails and fill them at the stream? George and I will carry them in. I’ll see you by the dipping pool.”

Hurrying with George into the sitting-room he heard the roar of the chimney on fire. There followed a wet five minutes, as pail after pail of water was flung into the grate and into the hip bath to soak a blanket for holding over the hearth, to stifle the soot flames in the chimney.

Soon the fire was subdued. George was suggesting a glass of whit-ale when there was an explosion in the cupboard beside the hearth. He opened the cupboard door as a second explosion scattered froth over them.

“Everyone out!” cried Phillip. “A glass splinter can blind you!” They herded into the kitchen, while further reports came from the cupboard.

“It’s the heat,” said George. “My word, it only shows the strength of the stuff, doesn’t it, Boo?” They counted six more explosions, whereupon George said, “All clear! I reckon that’s the lot. I’ll have to store the next brew in the scullery. Anyway I’ll get a new carpet out of the insurance—I’ll just chuck a few

cinders over it to scorch the edges of the holes that were there before! I’ll do it now, before the fire gives up the ghost!”

*

On the way back to the cottage Doris asked Phillip to walk with her up the lane. They stopped on the high ground, with its western line of sunset. To the north a steely blue glow arose to the zenith. Brother and sister looked into the immeasurable cavern of the sky. He felt tender towards her, she was his younger sister again, brave, resolute as ever; but lost.

“Phil, will you tell me the truth?”

“I’ll try to, Doris. But I’m not infallible.”

“Do you think that Bob puts on that face? I mean, they say that an actor can so think himself into his part, until he

becomes

the person he is pretending to be. And Bob was Percy’s best friend in the war.”