It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation (14 page)

Read It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation Online

Authors: M.K. Asante Jr

The Beastie Boys, the first white rap group, releases

Licensed to Ill

and becomes the first rap group to reach number 1 on the pop charts.

Eric B. and Rakim release

Paid in Full

on Zakia/4th & Broadway Records. Rakim’s use of elaborate metaphors, double puns, and paradoxes make it one of the most influential rap albums of all time.

I think it’s too late

Hip hop has never been the same since ‘88

.—

CANIBUS, “POET LAUREATE

,”

CANIBUS

N.W.A. (Niggaz with Attitude), a West Coast

group whose members include Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, DJ Yella, and MC Ren, releases their first album

Straight Outta Compton

, which goes gold and causes the media to dub their hardcore style “gangsta rap.”

Yo! MTV Raps

premieres on MTV with Fab 5 Freddy as host. The images, language, and styles featured on this show would help to nationalize Black youth culture.

The Omnibus Anti-Drug Abuse Act, designed to make existing laws even harsher and more unjust, is passed. The racism apparent in these laws is blatant. For instance, although crack and powder cocaine are pharmacologically the same drug, possession of only five grams of crack cocaine (predominantly used by Blacks) yields a five-year mandatory minimum sentence; however, it takes five hundred grams of powder cocaine (predominantly used by whites) to prompt the same sentence.

The Source

magazine, founded as a newsletter in 1988 by college students David Mays and Jon Shecter, releases its first issue. The magazine will grow to become the premiere hip-hop magazine in the world.

Jesse Jackson makes a second run at the U.S. presidency. Running on a campaign platform that includes reversing Reaganomics; declaring apartheid-era South Africa a rogue nation; issuing reparations to African-Americans; providing universal health care and free community college to all; and supporting the formation of a Palestinian state, Jackson, despite being briefly tagged a front-runner, would lose the Democratic nomination to Michael Dukakis.

Dr. Molefi K. Asante introduces the first Ph.D. in African-American studies at Temple University. Public Enemy and other Afrocentric rappers frequent the department. The department also encourages young scholars to write dissertations on hip-hop culture, advancing the discipline.

Bill Cosby, during the height of the popularity of his sitcom

The Cosby Show

, donates $20 million to Spelman College, the largest donation ever made.

Spike Lee’s film

Do the Right Thing

, a story about racial tension in a diverse Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, community, is released by Universal Pictures and features a soundtrack from Public Enemy. The film stars Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and Samuel L. Jackson and is the debut for Martin Lawrence and Rosie Perez.

Under international pressure, South African president F. W. de Klerk releases eight African National Congress (ANC) leaders from jail, including Walter Sisulu, founder of the ANC Youth League and

prominent figure in the formation of the militant MK or Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”).

The leader of 2 Live Crew

, Luther Campbell, gets arrested ’cause of the lyrics on

As Nasty as They Wanna Be

.

On February 11, Nelson Mandela, leader of the ANC, is freed from Victor Verster Prison in Paarl, South Africa, after twenty-seven years in prison. On the day of his release, Mandela spoke to the nation and to the world:

Our resort to the armed struggle in 1960 with the formation of the military wing of the ANC (Umkhonto we Sizwe) was a purely defensive action against the violence of apartheid. The factors which necessitated the armed struggle still exist today. We have no option but to continue. We express the hope that a climate conducive to a negotiated settlement would be created soon, so that there may no longer be the need for the armed struggle

.

Now I see her in commercials, she’s universal

She used to only swing it with the inner—city circle

.—

COMMON, “I USED TO LOVE H.E.R

.,”

RESURRECTION

Ice Cube writes

and performs an original song for a St. Ides Malt Liquor commercial. In the thirty-second commercial, Cube rhymes: “Get your girl in the mood quicker / Get your jimmy thicker / With St. Ides Malt Liquor.”

On January 16, the United States begins an unprecedented bombing campaign on Iraq, primarily targeting civilian life. The bombs, cumulatively, were the equivalent of seven Hiroshimas and resulted in the death of over 100,000 Iraqi citizens.

On March 3, Los Angeles police officers brutally attack and arrest Rodney King after a San Fernando Valley traffic stop. The beating of King is captured on videotape and quickly broadcast. All of the officers, during a trial that would take place the following year, would be acquitted—an event that sparks the second L.A. rebellions.

It’s nothin’ black about the head niggas that’s running the

industry, they not even niggas.—

JADAKISS

Foreigners, who have not studied economics but have

studied Negroes, take up business and grow rich.—

DR. HAROLD CRUISE

Black culture is too significant in American culture

for blacks to be glorified employees.—

RUSSELL SIMMONS

It has been said

that while a wise person learns from his mistakes, an even wiser person learns from the mistakes of others. Survival for the post-hip-hop generation means being deeply engaged in the latter and confronting, challenging, and correcting the issues that have plagued previous generations and paying special attention to those issues that have maintained a consistent presence throughout our history in America. One such issue is the relationship African-Americans

have had and still have with incredibly lucrative industries that, without us, would not exist as such.

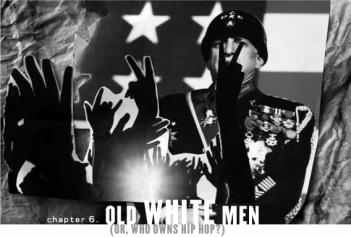

“Old white men is runnin’ this rap shit,” Mos Def, in his Brooklyn drawl, rhymed through the trembling speakers in the New York studio I sat in.

Corporate forces runnin’ this rap shit

Some tall Israeli is runnin’ this rap shit

We poke out our asses for a chance to cash in

.

My lips parted, not because I was surprised by what

he was saying

, but rather, that

he was saying it

. For so long, critical issues of power, race, and music have been neglected to the point where one wondered if the economic domination of Black music by non-Blacks was normalized beyond question.

The one-and-a-half-minute song continues as a lyrical indictment of an industry that tells Black performers to

get in the line of fire, we get the big-ass checks

. The song ends with a laundry list of culprits: MTV, Viacom, AOL, Time Warner, cocaine, and Hennessey.

A few weeks prior to hearing this song, I was a producer on

Blokhedz

, a short animated film for a digizine that Mos Def did a voice for.

Blokhedz

, a comic book created by Mike and Mark Davis of Imajimation Studios, tells the story of young Blak, an aspiring teenage rapper who is blessed with the mystical gift of turning his rhymes into reality. Living in the Monarch Projects of Empire City, Blak—who sports a red, black, and green wristband—must struggle to survive the violence and temptation of the streets, while also remaining true to himself and his gift. It was while working on this project, as I sat behind an engineer in a recording studio watching legendary movie director Michael Schultz

(Krush Groove, The Last Dragon, Cooley High)

, along with his son Brandon (a writer for

Blokhedz)

direct the voice-over

artists, that I heard this song playing in another section of the studio. I followed the beat.

Aptly titled “The Rape Over,” I learned that this song, which I was hearing a few weeks early, was slated to appear on Mos’s album,

The New Danger

. The song, like so many truths that surface in our lives, came to me at an important time. I was a student in college and had, over the course of my senior year, created

Focused Digizine

, an urban digital media enterprise with an estimated worth of $1 million. Part of our ability to raise funds and grow was due to the enormous amount of resources Lafayette College, a small, private liberal arts college with an endowment of more than $780 million, bestowed upon me: offices, interns, equipment, et cetera. In addition, this 94 percent white college located in rural Pennsylvania had resources that would bring me to point-blank range with the crisis.

“I want you to meet some of our board members and alumni in New York who are super successful and can help you. I don’t know much about what they do, but I know they are into the whole rap thing,” a fifty-something white administrator at the college told me.

Weeks later, I found myself, along with my producing partner, in robust Manhattan high-rises with fancy elevators and views that were surreal, meeting with executives from record labels, cable channels, and radio stations who were “into the whole rap thing.” Old white man after old white man, blazer after blazer, gray head after gray head, and striped tie after stripped tie, I was shocked to discover that hip hop’s decision makers weren’t hip hop at all. I quickly came to the realization that hip hop, this urban Black creation, was something that urban Blacks (or even just Blacks) didn’t control at all. The brutal fact is, as Afrika Bambaataa says: “Today a lot of the people who created hip hop, meaning the Blacks and Latinos, do not control it anymore.” These meetings symbolized how perhaps African-America’s richest cultural capital is outside of African-American hands.

It became clear that the hip-hop community and hip-hop industry were two totally different entities. As Yvonne Bynoe points out in her essay “Money, Power, Respect: A Critique of the Business of Rap Music,” the hip-hop industry “is comprised of entities that seek to profit from the marketing and sales of rap music and its ancillary products” and includes “record companies, music publishers, radio stations, record stores, music-video shows, recording studios, talent bookers, performance venues, promoters, managers, disc jockeys, lawyers, accountants, music publications, and music/entertainment websites,” most of which are not owned or even operated by the progenitors of the music—Black folks. Peep:

HIP-HOP COMMUNITY = THE STREETS

HIP-HOP INDUSTRY = WALL STREET

HIP-HOP COMMUNITY ≠ HIP-HOP INDUSTRY

Mos Def’s “The Rape Over” had validated what I was seeing, verbalized what I was feeling, and aired out what needed to be made public. What’s shocking is that he is among a select few to voice this gross disparity; it has been the proverbial elephant in the room. It’s easy to see why most rap artists would be deterred from challenging the institution that feeds them, but what about the critics, fans, and scholars? Most writers and critics who have written about hip hop have not approached the topic from a perspective rooted in history, making it difficult for them to fully assess the function of Black music in American life or to put forth a serious analysis of how hip hop and R & B undergird the entire music business. The most in-depth analysis usually arrives in the form of a moral objection to the content of the rappers’ lyrics rather than an analysis or scrutiny of the corporations that profit most from such “immoralities.” By focusing on the content, they unskillfully avoid the tough questions: Who

sponsors rap? Who buys the most rap? Who promotes death and violence? Who backs ignorance? Who exploits rappers? Who profits from Black-on-Black violence? Who owns the radio stations? Who owns TV? Who owns who, you and your crew? Who runs the media? Who runs radio? Who, who, who? Norman Kelley, one of the few writers to seriously address these disparities, reminds us in his essay “The Political Economy of Black Music,” “Never has one people created so much music and been so woefully kept in the dark about the economic consequences of their labor and talent by their intellectuals and politicos.”

However, all of that was about to change. Mos’s song,

I just knew

, would ignite all of our minds, pens, voices, and feet. It would spark new strategies about community control as well as expand upon discussions that needed to be had—discussions like Passage to Peace held at the 2004 Congressional Black Caucus in D.C., where Congresswoman Maxine Waters told the crowd: