Jack Adrift (14 page)

Authors: Jack Gantos

The parade was down at the fishing pier. By the time we arrived about fifty kids with their pets were gathered in the middle of the street. There were mostly dogs, but I also saw two goats, a pig, a lot of cats, some parrots, snakes, a jumping frog, a pony, a ferret, and a skunk that had been descented. There were no other ducks. We all had to sign in and declare what category we were competing in. There was no listing for ducks, so I put my name down under “Waterfowl.” Finally, a man dressed up as Dr. Dolittle announced the beginning of the Pet Parade! He began to march down the street with a cockatoo perched on his outstretched finger. The streets were lined with cheering people. Some of them I knew from school. First, the dogs were called to march. They lined up. Some were dressed with bandannas

around their necks and little party hats. One pulled a wagon with a toddler in the back. Then the cats were called. They went every which way. The goats were oblivious of everything except trash on the streets, which they tried to eat. The pig drew the most attention. His owner, a young girl, had dressed him up in a little sailor outfit, but he was still

Wilbur

to me.

around their necks and little party hats. One pulled a wagon with a toddler in the back. Then the cats were called. They went every which way. The goats were oblivious of everything except trash on the streets, which they tried to eat. The pig drew the most attention. His owner, a young girl, had dressed him up in a little sailor outfit, but he was still

Wilbur

to me.

Finally, it was our turn. I squatted down and gave King Quack a pat on his head. “This is your big moment,” I whispered. “Let's show 'em what you're made of.” And we walked with our heads held high down the center of the street. King Quack looked to the left and right and quacked to his audience as he waddled happily down the street. We were cheered every step of the way. My chest was puffed out with pride and when we passed by Mom and Dad and Pete and Betsy and they hollered out “Hail, King Quack!” I thought my cheeks would burst. King Quack waddled and stretched his wings, and his beautiful new white feathers reflected the sun. People stepped out of the crowd and took photographs of us and I thought it was the greatest moment of my life.

After we got our blue ribbon, the vet came up to me. “You did it,” she said. “Just look at him. He looks so happy.”

“Yes,” I said, “and I think we are going to keep him.”

“You can't,” she said. “He has to go find some other

ducks and live with them. He's grown up now and it's time for him to move on.”

ducks and live with them. He's grown up now and it's time for him to move on.”

“How will he find them?” I asked.

“Just leave him outside, uncaged,” she said. “He's feeling good now and before long he'll join up with other ducks around town.”

“Are you sure?” I asked. “I know he had a rough beginning to his life, and I just want to keep helping him.”

“You have to let him go,” she said. “You gave him all the help he needs to feel good about himself. Now he just has to do what ducks do.”

“Without me?”

“Without you,” she said.

We took him home and pampered him through the weekend but on Monday morning I took the chicken-wire cage down and left him alone. “Take your time and stick around here if you want,” I said. “But I'll understand if you need to get on with your duck life.” I knelt down and placed his blue ribbon on the ground by the side of the water.

“Quack,” he said.

“Quack,” I said back, and went on to school.

Miss Noelle had moved my desk to the back of the class and was kind enough to face it toward the window so I didn't have to look at a wall all day. For the three weeks while I took care of King Quack I didn't get lovesick about her at all. I listened to what she was

teaching us, and I did my work, but mostly I thought about King Quack.

teaching us, and I did my work, but mostly I thought about King Quack.

It happened right after lunch. I had just sat down at my desk for ten minutes of quiet reading when I looked up from my book and out the window. I saw a white duck flying away in the distance and wondered if it was King Quack. Then the sun struck at just the right angle and I saw a bright reflection of light flash off its beak and feet. That must be him, I said to myself, he's the most well-polished duck in town. I watched as he turned and then flapped his wings and became smaller and smaller, until I couldn't see him anymore. And then that sad feeling came over me. He was gone. But at least he was doing what ducks doâgoing to find other ducks.

Suddenly I looked up into the sky. “Look out for hunters,” I said. “I forgot to tell you about them.”

When reading time was over I knew my big test was coming. King Quack was gone. And with his departure I was free to think my romantic thoughts about Miss Noelle again. I put one of King Quack's feathers between the pages of my book to mark my place, then turned to listen to what she had to say about our science projects. As I listened, I rubbed the feather between my fingers. It was like rubbing a lucky charm. But it was a funny charm because it worked in reverse. Wishes came true before I even wished for them. I got over Miss Noelle and I never thought I wanted to. But now my

crush had disappeared and my time was spent thinking about real things rather than some silly fantasy of me and her driving through the Alps. And I began to look forward to going home so I could be nicer to everyone, because it was suddenly obvious that the nicer I was to them, the nicer they were in return. And finally I realized that

I

was the one who could have used a little boost to my self-esteem, and as a result I was more mature. King Quack had helped me more than I had helped him.

crush had disappeared and my time was spent thinking about real things rather than some silly fantasy of me and her driving through the Alps. And I began to look forward to going home so I could be nicer to everyone, because it was suddenly obvious that the nicer I was to them, the nicer they were in return. And finally I realized that

I

was the one who could have used a little boost to my self-esteem, and as a result I was more mature. King Quack had helped me more than I had helped him.

I looked out the window again. King Quack was long gone. But what he left behind was still in me. I loved that duck.

I

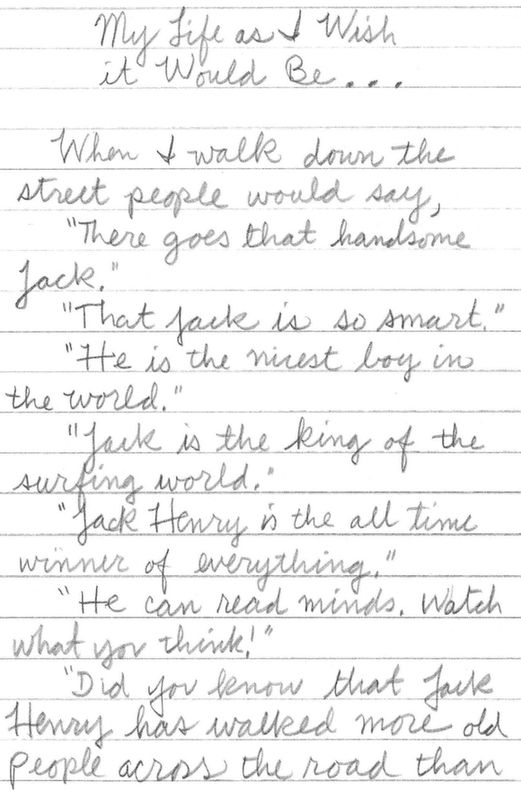

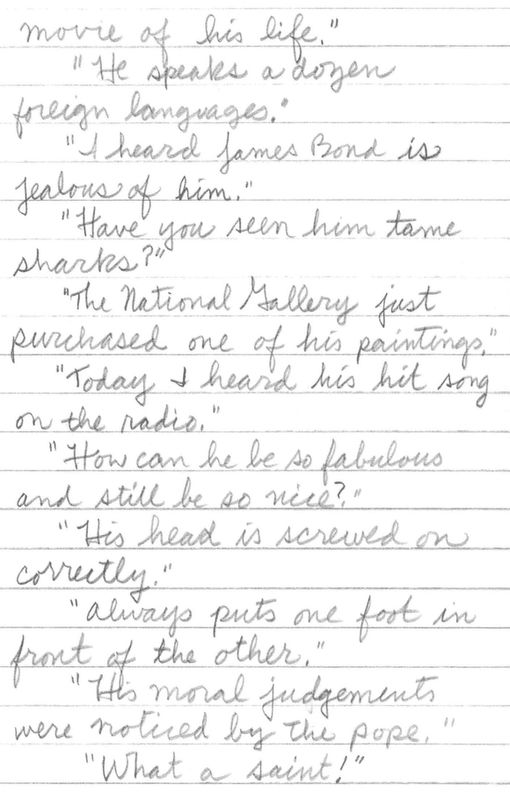

was sitting at the dining room table doing a book report on a famous American flier, but I wasn't writing very much. I was thinking that getting a C on the report was good enough. In class, Miss Noelle had made up a list from the Wright brothers to Amelia Earhart to Charles Lindberghâone flier for each kid. She gave me Will Rogers and said I reminded her of him because he was an “odd duck.” I looked at his picture and was disappointed because he was not very handsome. He had a wide, goofy-toothy smile and a piece of hay sticking out the corner of his lips. She didn't tell me he had died in a plane crash either.

was sitting at the dining room table doing a book report on a famous American flier, but I wasn't writing very much. I was thinking that getting a C on the report was good enough. In class, Miss Noelle had made up a list from the Wright brothers to Amelia Earhart to Charles Lindberghâone flier for each kid. She gave me Will Rogers and said I reminded her of him because he was an “odd duck.” I looked at his picture and was disappointed because he was not very handsome. He had a wide, goofy-toothy smile and a piece of hay sticking out the corner of his lips. She didn't tell me he had died in a plane crash either.

Reluctantly I began reading about him and before long I found he was so funny that, to anyone who would listen, I kept quoting things he had said. I wasn't getting much writing done, but reading his quotes was great fun. “Everything is funny as long as it is happening to

somebody else,” he had said. That seemed true. At school I saw a kid puke on another kid and I laughed about it all day. But it wouldn't have been funny if he had puked on me. And Will Rogers also had said, “Live your life so that you wouldn't mind selling your pet parrot to the town gossip.” That struck me as something to write down and keep in mind.

somebody else,” he had said. That seemed true. At school I saw a kid puke on another kid and I laughed about it all day. But it wouldn't have been funny if he had puked on me. And Will Rogers also had said, “Live your life so that you wouldn't mind selling your pet parrot to the town gossip.” That struck me as something to write down and keep in mind.

Then, like a sudden gale blowing through, Betsy and I got into an argument over one of his quotes. Will Rogers had said he'd “rather be the man who bought the Brooklyn Bridge than the man who sold it.” I agreed with him.

“Only an idiot could agree with that,” she argued. “How can you be so stupid? The guy who buys the Brooklyn Bridgeâwhich

can't

be boughtâgets nothing. And the guy who sells it gets all the money.”

can't

be boughtâgets nothing. And the guy who sells it gets all the money.”

“That's not the point,” I said. “It's not about money. It's about being a good person. He's saying he'd rather be gullible than be a crook. He'd rather be nice than be a creep.”

“Well,” she said, “I'd rather be rich than be an idiot.”

Dad heard everything from where he was sitting in the living room. “I agree with your sister,” he called out. “Besides, Will Rogers is overrated. He said he never met a man he didn't like.

Who

could believe that? I meet

some yo-yo every day I could run down in the street and never see again.”

Who

could believe that? I meet

some yo-yo every day I could run down in the street and never see again.”

Mom was down the hall cleaning the bathroom, but she could hear every word we said. “Well, I agree with young Jack,” she called out. “I'd rather be a bit naive and buy the Brooklyn Bridge and always see the good in people than be a rich crook who spends his miserable life thinking the world is filled with people to take advantage of.”

“Look at it this way,” Dad reasoned. “Rich people have a choice. They can see the good in people or the bad because they have the

time

to sit around and pick the lint out of their belly buttons. Poor people have to

work

all day long.”

time

to sit around and pick the lint out of their belly buttons. Poor people have to

work

all day long.”

It was kind of interesting listening and watching Mom and Dad debate with each other, even though they weren't in the same room. It really didn't seem like an argument. It seemed more like theater. And I knew, sort of, what they were going to say as if I had seen the play before.

“There is nothing wrong with honest hard work,” Mom continued, while scrubbing the toilet.

“But after you work for the Navy day in and day out, you begin to wish you had a few extra bucks,” Dad said.

“I don't have to work for the whole Navy to dream of a few extra bucks,” Mom said.

“Now don't start again about me not making enough money,” Dad said, with his voice rising.

Mom must have grimaced. Money was an issue. “I wish you would just listen to yourself,” she said.

“I can't listen to myself,” Dad snapped back. “I'm always busy listening to you.”

“And just what do you mean by that!” Mom said sharply, and stuck her head out of the bathroom to glare down the hallway.

Betsy gave me a weary look that said she was totally tired of me. “See what you started again,” she whispered.

“I mean,” Dad considered, calming down a bit, “that I'm always listening to your good advice. Why just last week I took a page out of your book.”

“How so?” Mom asked suspiciously.

“My commanding officer asked me how I felt about being in the service and I told the

truth,

and nothing but the truth. In so many words I told him this Navy job was for the birds. And guess what? He turned around and took a page out of my book. He told me exactly what I wanted to hearâthat

I

was for the birds. Then he offered me an early release and I took it. Signed on the dotted line.”

truth,

and nothing but the truth. In so many words I told him this Navy job was for the birds. And guess what? He turned around and took a page out of my book. He told me exactly what I wanted to hearâthat

I

was for the birds. Then he offered me an early release and I took it. Signed on the dotted line.”

Mom marched down the hall with the toilet brush held tightly in her yellow-gloved hand. She looked

shocked. “We'll stay on till the end of the school year, won't we?” she asked.

shocked. “We'll stay on till the end of the school year, won't we?” she asked.

“Yeah,” he replied. “It will take a while for the discharge paperwork to come through and by then school should be over and we can stop living in this sardine can and move on to greener pastures.”

“Well, I can't argue with that,” she said. “But what kind of discharge are you getting?”

He sort of looked the other way, as if someone were calling him, but I knew he didn't want to look Mom in the eye.

“An O-T-H,” he said quickly.

“I've never heard of that before,” she said. “What's it mean?”

“Other Than Honorable,” he said casually. “It just means that we have agreed to go our separate ways. They neither love me nor hate me. It's neutral.”

“Why aren't you getting an honorable discharge?” she asked.

“Let's just say,” Dad replied, “that every day I showed up for work I complained, until I finally wore them down and now they've decided to set me free to do what I want to do.”

“And now they think you are a lousy worker,” she said.

“What's it matter? I'll never see them again.”

“Maybe so, but what about your self-pride?”

“I never let pride stand in the way of what I want,” he said. “If some people think I'm a jerk, that's fine with me as long as I can get what I want.”

“Well, I'd rather be able to hold my head up high in front of any kind of people.”

“Hey, I'd just rather head on out,” he said. “Out of sight, out of mind. That's my rule.”

“And one I should put to use right now,” she said, turning and marching back down the hall.

I was just imagining what Act II might be between Mom and Dad, when Betsy slowly stood up and leaned over me.

“Hold still,” she cautioned, as she raised her open hand behind her head. “This is going to sting, but don't think about it or you'll twitch.”

Then she cut loose.

Slap!

She smacked me across my ear. I thought I'd been hit with a baseball bat. My Will Rogers book flew to the other side of the room and I slipped off the edge of my chair.

Slap!

She smacked me across my ear. I thought I'd been hit with a baseball bat. My Will Rogers book flew to the other side of the room and I slipped off the edge of my chair.

“Why'd you do that?” I yelped, and hopped up.

“Mosquito,” she said. “They carry yellow fever. I may have saved your life.”

“I think you just wanted to hit me because you're in a bad mood,” I said.

She scoffed. “Check your ear,” she ordered.

I wiped my finger over my stinging ear, then looked at it. There was blood.

“See,” she said. “I nailed a big fat one. You should thank me.”

“For puncturing my eardrum?” I replied.

“No,” she argued. “I killed something that had obviously

punctured

you.”

punctured

you.”

I didn't want to believe her. I wanted to think she was just mean enough to suddenly haul off and swat me around the room like a tetherball. But she was right. We were having a big mosquito problem. They were everywhere. At night they were matted up against the window screens like a fur coat. Mom kept citronella candles lit around the doorways, but that didn't scare them off. When the front door opened, mosquitoes poured in like water. We chased them around the house with rolled-up newspapers, flyswatters, and slippers. Some mosquitoes were so full of blood that when we smashed them against the wall, they splattered like tiny balloons full of paint. Mom patrolled behind us and washed the splat marks off the wall, but I could still see a faint gray-and-red stain left behind.

With everyone in such a bad mood, I went outside to sit. I'd rather fight with mosquitoes, I thought while rubbing my ear, than with my family. I sprayed myself with bug repellent and stood next to the swamp. The

mosquitoes buzzed around my face but they didn't like the kerosene smell of the spray. When I looked east it was already dark. When I looked west the sky seemed to have a purplish black eye. It was hard not to think about the differences between Mom and Dad. For Mom, life was about being a good person and living with pride. Dad just wanted to get ahead any way he could. I wished I could be both of them, and get ahead

with

pride. But by the way they talked you had to choose to be one or the otherânot both. I knew we would leave Cape Hatteras but I should try harder to “live up to my potential and get better grades” as Miss Noelle had put it. Just because I knew I would never see her again didn't mean I could slack off.

mosquitoes buzzed around my face but they didn't like the kerosene smell of the spray. When I looked east it was already dark. When I looked west the sky seemed to have a purplish black eye. It was hard not to think about the differences between Mom and Dad. For Mom, life was about being a good person and living with pride. Dad just wanted to get ahead any way he could. I wished I could be both of them, and get ahead

with

pride. But by the way they talked you had to choose to be one or the otherânot both. I knew we would leave Cape Hatteras but I should try harder to “live up to my potential and get better grades” as Miss Noelle had put it. Just because I knew I would never see her again didn't mean I could slack off.

I looked out at the mosquitoes. They were rising up from the swamp like clouds of black smoke. “It's going to be life or death for you guys,” I shouted. “You can't choose both!” I stepped forward and sprayed at a cloud of them. A few with drenched wings fell into the water and struggled until a small frog popped up from the swampy ooze and swallowed them. But no matter how many I killed, or were eaten, we couldn't keep up with how rapidly they were hatching. Mom had called the health department and they had promised to come out and spray the swamp, but the epidemic was everywhere and the spray trucks were busy in rich neighborhoods.

It was a relief to me when Julian came out of his

house wearing a khaki explorer's hat with mosquito netting that covered his entire head and was tucked into the neck of his T-shirt.

house wearing a khaki explorer's hat with mosquito netting that covered his entire head and was tucked into the neck of his T-shirt.

“Guess what-what-what!” he hollered.

“You're going on a safari,” I replied.

“No,” he said, grinning. “We're moving. My-my-my dad quit the Navy.”

Other books

The Gap Year by Sarah Bird

A Play of Knaves by Frazer, Margaret

Sea of Troubles by Donna Leon

Between the Roots by A. N. McDermott

The Gunslinger’s Untamed Bride by Stacey Kayne

Second Nature by Alice Hoffman

Death Row Apocalypse by Mackey, Darrick

Galactic Freighter: Scourge of the Deep Space Pirates (Contact) by Ingle, Kenneth E.

On Steady Ground (The Walker Brother's Series) by Anderson, Jennifer