Jack the Ripper: The Secret Police Files (36 page)

Read Jack the Ripper: The Secret Police Files Online

Authors: Trevor Marriott

The issue of revealing the identities of informants was the main reason for the files being suddenly closed in 2007, and the subsequent reason for Alex Butterworth to lodge and appeal following his initial request to view the ledgers and register and to be able to freely print and publish information gathered from them. He was given the opportunity of also signing a written undertaking the same as Felicity Lowde but refused. In the light of the fact Felicity Lowde signed it and reneged on it and it appears no further action being taken I suspect Mr. Butterworth now wishes perhaps he had done what she did.

Ms. Lowde’s assessment and evaluation of some of the information contained within these records is interesting. She has obviously carried out research into the Whitechapel murders. She is one of a number of Ripper researchers who subscribe to the Royal Conspiracy theory. She suggests that Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes and her common law husband John Kelly were acting as spies/informants for Special Branch working directly under Chief Inspector John Littlechild. She suggests Eddowes was actively seeking information from members of the International Workers Club in Berner Street.

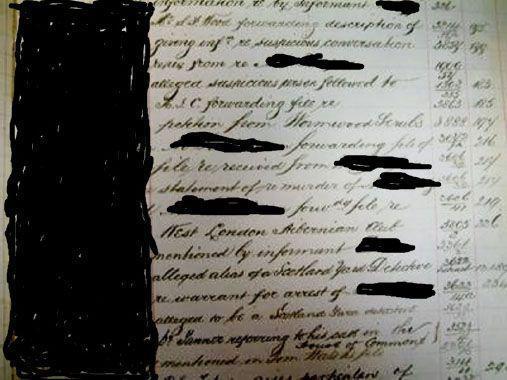

In support of her theory, Ms. Lowde refers to two specific undated entries in the register. These entries relate to a John Kelly and Catherine Kelly as shown in (Picture 16), which is the unredacted page from the register which she photographed and published and refers to. It is accepted that Eddowes also used the name Catherine Kelly with a nickname of “Kitty” and she was in a relationship with John Kelly. Ms. Lowde states that two Kelly entries recorded in the register relate to Eddowes and John Kelly who she suggests were members of the Jenkinson spy ring. The Jenkinson referred to is Edward Jenkinson a government civil servant who ran a network of spies for the British Secret Service up until 1887/88 before going back to his previous post as assistant under secretary for police and crime based at Dublin Castle.

On examining the relevant page from the ledger, which she published and is still today shown on her web blog, it is clearly not the case. The register entry does not corroborate what she suggests. Furthermore, she states that the entry relating to John Kelly shows him receiving a file directly from Jenkinson on the Fenian assassination of a man named McDoughty. My interpretation of this is completely the opposite. It is normal practice that when murders occur witnesses are seen and interviewed and any statements that they make in relation to that enquiry are documented before being filed. This to me is clearly a case of a statement that Kelly has made in connection with this murder and has subsequently been documented and later filed.

As far as the entry relating to John Kelly is concerned, she states that it shows him receiving a file from Jenkinson. However, again reading the entry this is clearly not the case. The entry clearly relates to one of a number of files the Metropolitan Police received from Jenkinson who was asked to hand over his files to the newly formed Special Branch before he left his post in 1887.

There are other entries in the register, which confirm my belief. In staying with the John Kelly entry a further examination of newly found police records reveals a John Kelly aka John Moran who was an informant working for both the British and Irish Governments in 1886. He was relocated to Canada and subsequently received yearly payment from the British Government after being relocated these are recorded up as far as 1887 so I would suggest the John Kelly shown in the register are one and the same and not the common law partner of Catherine Eddowes as suggested by Lowde’s. This negates her theory that both were working as spies for Special Branch.

With regards to Ms. Lowde’s theory, she even goes so far as to say that Chief Inspector Littlechild was actually responsible for Eddowes murder and also ordered the murder of Mary Kelly, as both were planning to reveal details involving the indiscretion of Prince Albert Edward Victor and his alleged association with Mary Kelly which resulted in her allegedly giving birth to a love child who was subsequently spirited away by Special Branch officers. This version differs from the other version where Annie Crook is named as having given birth to a royal love child of Prince Albert Victor.

I cannot accept what Ms. Lowde is suggesting in relation to the entries. It is a fact that all the entries are undated. It is now clear that all of the entries in the register were entered retrospectively en masse after 1894, and although the entries in the register relate to files formulated from February 1888, there is clear evidence to show that earlier files predating February 1888 were also entered in the ledgers. The entries referred to by Ms. Lowde and other entries on that same page are proof of that.

With regards to the entry regarding the McDoughty murder I have closely examined this entry and the entry could in fact refer to a “Mr. Doughty” and not “McDoughty”. The person who made all of the entries has made such a small entry prefixing the surname it could be either. In any event I could find no specific references or details of any murders in either name. I did find an entry in The Guardian newspaper dated November 23rd 1887. Part of the article related to a Henry Doughty and having regard to the date and the fact that the entry in the register could have related to that same time period they could be one and the same. The entry in the ledger refers to a specific murder however, it could be the case that it was a plot to murder which never came to fruition; the article shows Henry Doughty as an Irish activist and he without a doubt would have come to the notice of police. The extract reads:

“Mr. Henry Doughty, who calls himself the London workingmen's delegate to Ireland, was on Friday last sentenced to a month's imprisonment for inciting people to adopt the Plan of Campaign and to join the League in a proclaimed district. Mr. Doughty on hearing the sentence rose, and, waving his hat in the air, shouted “God save Ireland." The cry was taken up by the people in court, a number of soldiers belonging to the Leinster regiment being especially demonstrative. The magistrate immediately sentenced a countryman who was arrested in the act of observing for O'Brien to a week's imprisonment, and the tumult subsided. Mr. Doughty was subsequently removed to the gaol at Limerick, care being taken to prevent anything like a disturbance on the way.”

In February 2009 Alex Butterworth’s Freedom of Information appeal was heard. It should be noted that despite lodging the appeal Alex Butterworth was not notified of the date of the hearing, nor was he given the opportunity to attend and to add more weight to the appeal or call any witnesses in support of his appeal, turning the appeal hearing into a one-sided affair.

During the appeal the Metropolitan Police went to great lengths to emphasize to the appeal tribunal the importance of not disclosing the identity of informants. In fact they went so far as to say that it was not possible to distinguish in the ledgers and register as to what information related to informants and what did not. This without a doubt was a misleading statement, which in my opinion had a major impact on the tribunal’s final decision.

Due to the overwhelming police evidence much of which was heard in closed session the information commissioners conceded defeat and a compromise was made between the Metropolitan Police and the Freedom of Information Commissioner, both agreeing that the ledgers and register could be made public subject to all proper names being redacted out. This made the ledgers and register nothing more than a black mass of the redactors pen. To show this more clearly the same unredacted page previously referred to in (Picture 15 ) is now shown following the redacting process in (Picture 16 ).

Following this decision I went to inspect copies of the register and the ledgers. It became clear that despite all the redaction it would have been a relatively easy task for someone like me or in fact any other experienced police officer to go through the register and ledgers and be able to distinguish which entries related directly to information given by named informants and that which did not.

Even in redacted form it soon became apparent that the register was an early form of collators record used to collate information submitted by police officers. When I joined the police service in 1970 we operated collators systems. This was in the form of a card index system. Information was manually entered on index cards by officers working in the collator’s office.

This was information submitted to the office by officers on the beat etc. It would include general information about crime and criminals, motors vehicles connected to suspects etc. The information would have been either gathered by officers themselves or could have been passed on to them by informants or members of the public. It should be said that it was not always accurate and reliable and in some cases may have been as a result of malicious intent by the provider.

On further examining the register not only had the names of informants been edited out but all others names, which are clearly not informants had also been edited out. The first thing that struck me was that despite all the editing out of these ledgers it could be seen that they contained a wealth of information. I would have to say these ledgers and register are some of the most informative and interesting vintage police documents I have come across, and to think these ledgers were offered to The National Archives and they declined to take them stating they contained no useful information.

After going through the register in redacted form I did find four interesting undated entries regarding Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel murders.

The first entry was under a specific entry titled Jack the Ripper, the entry read, “

The name given to suspect -------- at Bushmills”

followed by a file reference number obviously the name has been redacted out. The missing file would have contained the relevant information as to why that person had been considered to be a suspect.

The second entry found was an entry from Chief Inspector Littlechild, which read, “

Suspect --------- & The Whitechapel Murders”

followed by file reference number. Again the name has been redacted out, and again the relevant now missing file would have contained an entry as to what the information was to make Littlechild submit the information to be recorded.

The third entry read, “McGrath, William – “

said to be connected to Whitechapel murders””

The fourth entry read, “McGrath, William – “

suspicious Irishman at 57 Bedford Gardens””

In addition at the back of the register were references made to anonymous letters received by Special Branch regarding the Whitechapel murders. I would have imagined that perhaps the contents of these may have been entered under separate register entries and may have even been the specific entries referred to above.

The names, which are shown in the four specific entries, could have been the names of Ripper suspects already known. Or they could just be names suggested by informants or names simply given to the police, which warranted further investigation. If they were to reveal names of new suspects the Ripper mystery would be thrown wide open yet again. There may of course have been other vital information regarding Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel murders in the ledgers and the register, but due to the heavy redacting I found it almost impossible to assess and evaluate all the entries fully.

Undeterred by this I then submitted a number of additional specific requests to the Metropolitan Police under the Freedom of Information Act to access the ledgers and register in unredacted form. These requests were centred around the four entries from the register and any other entries relating to the Whitechapel murders and Jack the Ripper, which may be contained in them but due to the heavy redaction were not readily visible. At the time I emphasized to the police that I had no interest in informants or disclosing the names of informants. Despite all of this the Metropolitan Police again rejected all of my requests.

The police were using the Butterworth appeal decision for their basis of the constant refusals. I then lodged an appeal with the Metropolitan Police on all their decisions to refuse access. This is an appeal conducted internally by the police, needless to say as expected, was also unsuccessful. This is a ridiculous part of the Freedom of Information process whereby the police review a decision made by them via a different department.