Janette Turner Hospital Collected Stories (6 page)

Read Janette Turner Hospital Collected Stories Online

Authors: Janette Turner Hospital

He saw the tear rim down Miss Jennifer Harper's cheek and frowned with disgust. He felt vindicated. Integrated. Both Hindu and Marxist teachings agreed: compassion and sentiment were signs of weakness. The West was indeed decadent.

* * *

Jennifer Harper concentrated all her energy on waiting. There is just this one last ordeal, she promised herself, and even if I have to wait all tomorrow too, it must come to an end. I will not let the staring upset me. There is just this last time.

After months of conspicuous isolation as the only Western student at the University of Kerala, she was leaving. She wondered how long it would be before her sleep was free of hundreds of eyes staring the endless incurious stare of spectators at a circus. Or at a traffic accident. If one saw the bloodied remains of a total stranger spread across a road, one watched in just that way â with a fascinated absorption, yet removed, essentially unaffected.

She looked up at the counter with mute resignation. Surely her turn would come today. Inadvertently, she became aware of the intent gaze of the gentleman who had arrived next after her that morning. He also had waited all yesterday, but it did not seem to ruffle him. Nor did he show any sign of the exhausted dejection she had felt. Time means nothing to them, she thought with irritation. She decided to meet his gaze evenly, to stare him into submission.

He did not seem to notice. Her eyes bounced back off a stare as impenetrable as the packed red clay beneath the coconut palms. She felt as stupid and insignificant as a coconut, a stray green coconut that falls before its time, thuds onto the unyielding earth, and lies ignored, merely something for the scavenger dogs. It was intolerable. She could feel tears pricking her eyes.

Damn, damn, damn, she thought, pressing her hands together with all the force of her desire not to fall apart from the heat, the exhaustion, the dysentery, the inefficiency, the interminable waiting. Just this one last little thing, she pleaded with her self-respect. Then a name was called, and the impertinent staring gentleman went to the counter. They had missed her name by accident. But what would be the good of attempting to protest? Communication would be a shambles. The clerk would be confident that he was speaking English but would be virtually unintelligible. He would understand almost nothing she was trying to explain. Then she would try her halting Malayalam, but all her velar and palatal rs and ls, and all those impossible ds and ts, would get mixed up, and the people in the room would stare and giggle. Better to wait. He would soon notice that he had omitted a name.

There was a blare of loudspeakers passing the office. No one paid any attention to it. Every day some demonstration or other muddled the already chaotic traffic of Trivandrum's main road. If it was not the Marxists, it would be the student unions of the Congress party or the Janata party marching to protest each other's corruptions. Or it would be the bus drivers on strike, or the teachers picketing the Secretariat, or the rubber workers clamouring for attention, or perhaps just a flower-strewn palanquin bearing the image of some guru or deity.

The blast from the loudspeaker was so close that those at the counter could not hear one another speak. There was a milling crowd at the Air India doors, which gave way suddenly to the pressure of bodies. Mr Chandrashekharan Nair blanched to see several Marxist leaders. He was going to have to make some snap decision that might have frightening repercussions for the rest of his life. He breathed a prayer to Lord Vishnu.

Mr Matthew Thomas, who knew that the ways of God were inscrutable but wise, felt that something important was about to happen and waited calmly for it.

Jennifer Harper thought with despair that the office would now be closed and she would have to come back again the next day.

The student leader made an impassioned speech in Malayalam, which culminated in a sweeping accusatory gesture toward Jennifer. She rose to her feet as if in the dock. The student advanced threateningly, glared, and said in heavily accented English: â'Imperialists out of India!” In equally amateur Malayalam, and in a voice from which she was unable to keep a slight quiver, Jennifer replied, “But I am not an imperialist.”

There was a wave of laughter, but whether it was directed at her accent or her politics she could not say. Several things happened so quickly that she could never quite remember the order afterward. First, she thought, the gentleman who had stared so hard stepped between herself and the student, protective.

At the same time, the clerk at the desk had said, with a rather puzzling sense of importance, that he was especially arranging for the American woman to leave the country as quickly as possible. At any rate, she was now in a taxi on her way to the airport with nothing but her return ticket and her pocket-book. Next to the driver in the front seat was the gentleman who had defended her. She was thinking how sweet and easy and simple it was to sacrifice the few clothes and books, the purchased batiks and brasses, left back at the hostel. But the gentleman was saying something.

“My name is Matthew Thomas and I am having a daughter in Burlingtonvermont. I am hearing you say this place yesterday, and I am thinking perhaps you know my daughter?”

She shook her head and smiled.

“My daughter ⦠I am missing her very much ⦠She is having a child ⦠There are many things I am not understanding ⦔

They talked then, waiting at the airport where the fans were not working and the plane was late. When the boarding call finally came, Jennifer promised: “I will visit your daughter, and I will write. I understand all the things you want to know.”

Mr Matthew Thomas put his hands on her shoulders in a courteous formal embrace. She was startled and moved. “It is because you are the age of my daughter,” he said, “and because you go to where she is.”

Mr Chandrashekharan Nair watched the plane circle overhead. He was on his way to the temple of Sree Padmanabhaswamy to receive prasadam and to give thanks to Lord Vishnu. He had just made a most satisfactory report of the incident to the newspaper reporter, and had been able to link it rather nicely to the Coca-Cola issue. It was a most auspicious day.

The ways of God are truly remarkable, thought Mr Matthew Thomas as he left the airport. To think that the whole purpose behind the education of his wife's cousin's son had been the answer to his prayers about Kumari.

Jennifer Harper watched the red-tiled flat roofs and the coconut plantations and the rice paddies dwindle into her past. “Oh yes,” she would say casually in Burlington, Vermont. “India. A remarkable country.”

Ashes to Ashes

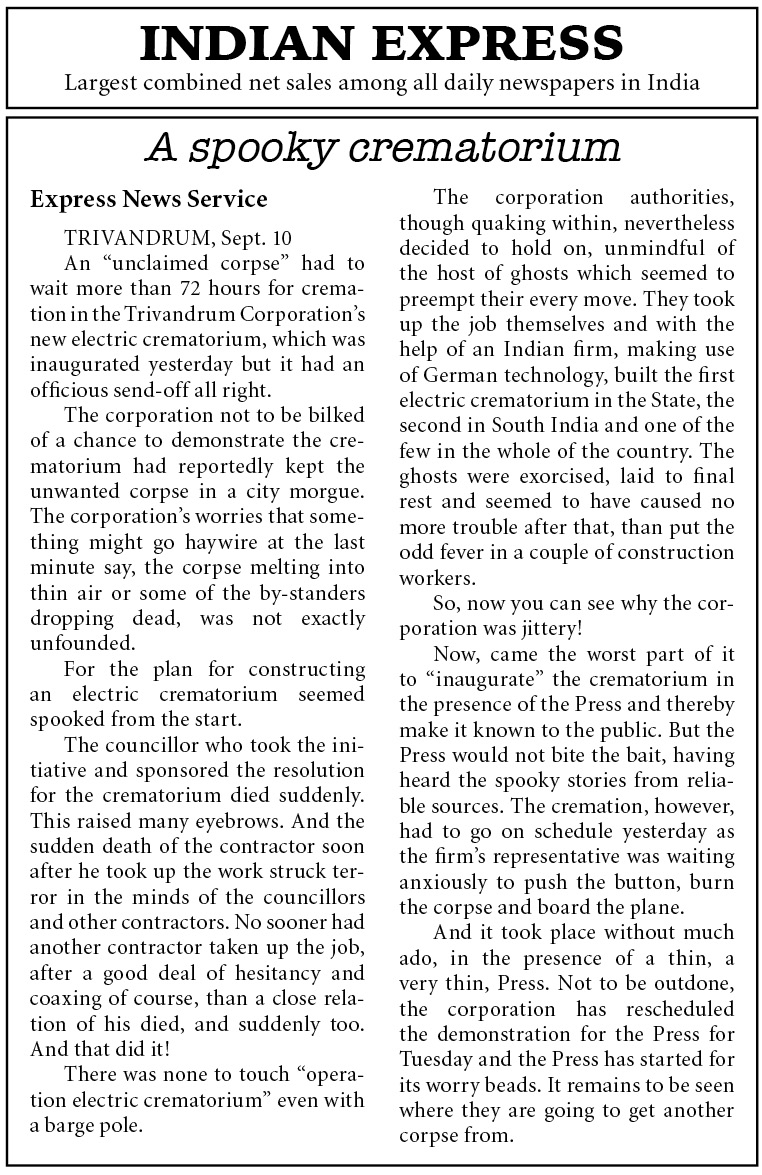

Corpses, that is the answer. Corpses are my future, thought Krishnankutty with elation and smiled upon his bride Saraswathi as they exchanged the garlands of flowers. She was dazzled by the light of his destiny. It is love, she thought, for she had a college degree in English literature and was an avid reader of Barbara Cartland, Victoria Holt, and other English novelists circulated in paperback among the well-educated and well-born young women of Trivandrum. She recognised the bold and dark passion of the foreign-returned man and quivered with delicious fear.

Krishnankutty took it as an auspicious sign. Corpses, he saw unmistakably, were his

karma

and his fortune. He had experienced a moment of enlightenment and she had perceived it. After the tying of the

tali

they held hands in an ecstasy of mutual misunderstanding. They had seen each other only once before, in the presence of others, and neither had been displeased with the parental choice, but nor had either expected such incandescence. It was the prelude to a night of passion. Krishnankutty had read the

Kama Sutra

while he was a graduate student at MIT â it had been lent to him by his American friend John in a paperback English translation â and that night he laid claim to his Indian heritage. Saraswathi, who had never heard of the

Kama Sutra,

felt that the glorious mysteries of American sex had been revealed to her.

In the morning he told her his plan. It had come to him, he said, at the instant he had seen her face framed by the bridal garland of jasmine. His American education and his Indian nationalism had merged with the nuptial embrace, and the idea of the electric crematorium had been conceived. It would be the first in the state of Kerala, perhaps the first south of Bombay (though he suspected there was already one in Madras), and certainly one of the few in the whole country.

On the way to the wedding, the groom's party had crossed paths with a funeral procession. The bier was thickly flower-strewn, and even the bearers, carrying it high over their heads, had been weeping. The corpse was that of a beautiful young woman.

Krishnankutty's American friend John â he of the

Kama Sutra

loan â had considered himself fortunate to have his movie camera at the ready, being engaged in recording the procession from the groom's house to that of the bride. In a

frisson

of Eastern excitement, anticipating, he felt, the ultimate perfection of

moksha,

he captured forever on the one reel the continuity of life and death. It was just as Hermann Hesse had intimated in

Siddhartha

â a wedding, a funeral, the beggars at the roadside, the lavish silks and jewels of the bridegroom's party, the river of life flowing on, the vast oneness of it all.

But Krishnankutty's mother, Lakshmi, had been aghast at such an inauspicious encounter. Weeping and trembling, she had begged her husband and son to postpone the wedding lest disaster strike the young couple. Krishnankutty, however, with his American education in electrical engineering, was not worried by such things. Was not this

Chingam,

the auspicious month for marriages? And had not the astrologer consulted by the family indicated that this particular hour on this particular day was the auspicious time?

Clearly then some special thing, good rather than evil, would come of the meeting. And so it had been.

The funeral had reminded Krishnankutty of the final rites for his friend John's mother. She had lain in state, surrounded by flowers, in a room at the funeral home. Krishnankutty had been greatly impressed by the furnishings and wall-to-wall carpet of this room, and by the restrained grief and decorum of the visitors. Later he had marvelled at the quiet simplicity with which, at a certain point in the chapel service at the crematory, the coffin had smoothly rolled out of sight behind a velvet curtain at the unseen touch of a remote control button. The next week he had returned and expressed his professional interest as an engineer, and the management had given him a tour of the crematorium, the discreet workings of which had fascinated him.

Krishnankutty was embarrassed by John's interest in the funeral procession. He strongly suspected that his friend would briefly slip away from the wedding festivities to film the burning of the young girl down on the river bank. He visualised his former acquaintances in Cambridge, Massachusetts watching on screen the blatant leap of flames around the pyre, the muddy river and its filthy excremental banks, the extravagant wailing of the family â all confirming their image of India as a romantically primitive place. It was so unfair. He knew John would not bother to photograph the Shree Kanth, Trivandrum's modern two-storey air-conditioned cinema, which not only showed nightly films in Malayalam, Hindi, and Tamil, but also ran an American movie once a month.

Krishnankutty was, in fact, planning to take his new wife to see the famous James Bond in

Live and Let Die.

He would undertake to open her eyes to the modern world. All these thoughts had been running through his head until the moment she had raised her face to him. He had then experienced a sort of vision in triplicate â the faces of Saraswathi, the recent corpse, and John's mother, all ringed with flowers, hazily intermingling like a multiple-exposure colour slide. It had then come to him that his mission was to establish in Trivandrum an electric crematorium. It was the answer to his newly graduated, newly returned zeal to do something for his country. Not only was it the ideal way to utilise his qualifications, but it would also contribute substantially to the modernisation of the city and would incidentally bring him fame and fortune.

John, when confided in a few days later, was appalled by the plan. He did not have the restless problem-solving mind of an engineer.

“It's practically obscene, Krish,” he objected, still full of the beauty of the oneness of all things.

The two friends had met not in university classes, but in the rambling old frame house where they both rented one-bedroom apartments. Since Krishnankutty could not cook, John frequently shared his vegetarian and macrobiotic cuisine. John's family had so much money that it was only natural he should turn from things material to things spiritual. He had been delighted to come to India for his friend's wedding. He decided to stay on. He felt geographically closer to enlightenment, sensed a speeding-up in his search for truth. A crematorium among the coconut groves, it seemed to him, would interfere with the search.

“It's a dreadful idea, Krish,” he repeated.

“What do you mean?” asked Krishnankutty, wounded. “You are taking photographs of the lighting of the pyre at the river bank. The water is smelling very bad, and the bank is having much filth, isn't it? Yes, yes. Are these rites suitable for modern educated peoples?”

“Your rites are elemental and beautiful, Krish. One's ashes mingle with the ash and mud of life itself, down there. It is so much purer than the commercial racket of the death industry back home. It would be criminal to change it.”

Krishnankutty thought sourly: Those who have already seen their parents croak in style (he was proud of his grasp of American idiom), with the dignity of wall-to-wall carpeting and unseen flame, can afford to be romantic about squalor and the acrid smell of burning flesh.

Krishnankutty wasted no time. Achuthan Nair, a cousin on his mother's side, was a city councillor. Krishnankutty invited his relative to dinner and revealed to him the splendours of his proposal. He volunteered to draw up designs, in collaboration with an architect, and to submit them to the Corporation of Trivandrum if Achuthan Nair could win that body's support and funding of the scheme.

Achuthan Nair's speech to the Corporation was considered notable, particularly in retrospect. It began with a quotation from Hamlet, which was most impressive.

Alas! poor Yorick,

said Achuthan Nair, inviting the councillors to gaze on the imaginary skull in his hand. How was this sort of noble sentiment possible, he demanded, without lasting mementos of the dead? And even though one's father would return in another form, did not a man cherish the life of his father as he had known it? Would not a small urn of ashes and a plaque bearing the father's name be something of beauty and dignity to be cherished by the family?

There were uneasy diggings at dhotis and stirrings of sandalled feet, and Divakaran Nambudiripad, an elderly and respected Brahmin, interjected angrily: “Contamination! All is contamination!” The old man rose to his feet. What could be compared, he demanded, with the beauty and dignity of standing on land's end at Cape Comorin where Gandhiji's ashes had been scattered to the elements? What sentiment could the trivial West offer to compare with the religious grandeur of that stormy point where three seas met and where one could be reabsorbed into the universe?

But there were others who were more progressively minded, and they wanted Achuthan Nair to continue. He appealed to Kerala's reputation for enlightened advancement; he alluded to the reformist legacy of His Highness the Maharajah of Travancore; he pointed out that Gandhiji himself had studied in the West and had not been afraid to learn from it; he quoted, with a beautiful cadence, from Keats on the brevity of life, and ended in a crescendo of Milton.

His audience was swept before him. The motion was passed, the money allotted, and a contractor designated. There was a general feeling of well-being, broken only by the mutterings of Divakaran Nambudiripad who warned darkly of the

Kali Yuga,

that Last Age of decline and dissolution.

Two weeks later, when Achuthan Nair died suddenly of a heart attack, Divakaran Nambudiripad felt vindicated and the rest of the Corporation somewhat shaken. But the contractor had been hired and work on the project was already under way. Krishnankutty himself appeared before a special session of the Corporation and spoke with fervour of the rightness, the modernity, and the necessity of the enterprise. With a majority of the city councillors still behind him, he daily supervised the construction site and each nightfall distributed the day's wages to the Harijan labourers.

He invited John to film the work in progress. Not very enthusiastic, John brought his movie camera but was then delighted by the photographic possibilities. He was surprised to see as many women as men engaged in the heavy work. He watched, breathless, running his film, as four men struggled to lift a great piece of rock for the foundations. Painfully they raised it, and then placed it carefully on the head of a squatting woman, very young and beautiful, with only a small coil of braided coconut leaf on her glossy hair to support the rock. When it was properly balanced, the four men let go and the girl very slowly rose to full height and walked across to the foundation, where she again stooped so that several men could lift the rock and place it in position on the wet mortar. This operation was repeated many times and the wall inched its way upward.

“Incredible!” said John. “Beautiful! Tragic!”

“Tragic?” Krishnankutty was startled.

“Such fragile bodies for such brutal work!”

Krishnankutty watched the labourers with surprised interest. Now that he thought about it, it was unusual. He had never seen women on construction sites in America. “Our poor people are very strong,” he said proudly. “They are having simple and happy lives.”

John was both disturbed and uplifted by the incident. He retreated into contemplation. Suffering in India, he felt, had a sort of ineffable beauty about it, framed as it was by lush rice paddies and coconut groves and the smell of incense and jasmine garlands in the market-place. He took to sitting by the temple baths each day, talking to the old men who sat on the stone steps in the sun. It was a source of grief to him that Kerala (unlike other Indian states) did not permit non-Hindus to enter the temples. Each day he meditated in view of the busily carved

gopuram

of Shree Padmanabhaswamy temple, longing to stand in the presence of Lord Vishnu. He saw less and less of Krishnankutty, found a guru who would help him read the

Vedas,

searched as far afield as Tiruvannamalai to find an ashram that would initiate Westerners as Hindus, after which he decided to set out on foot to Cape Comorin as a pilgrim.

In the third month of Krishnankutty's project, when the exterior walls had risen impressively from the foundations, the building contractor was seriously injured in a fall from the scaffolding, which had been improperly roped together. His back was broken, he lived on for three days of agony, and died murmuring that perhaps Lord Vishnu was offended by the crematorium.

The Corporation was in an uproar. Even Krishnankutty was shaken, yet so certain was he that his inspiration, coming as it had in the high nuptial moment, had been an auspicious one, that he could not easily abandon his dream. He consulted an astrologer, and when that man gave him an unfavourable reading he consulted another one. The second prediction was genial, and armed with this reassurance he again went before the councillors. The task was long and difficult, but he eventually regained the backing of a bare majority.

However, it proved to be impossible to hire a contractor anywhere in the district of Trivandrum. Word had even spread as far north as Quilon, but finally a man from Cochin, who had heard nothing of the matter, agreed to supervise the construction if his accommodation were provided in Trivandrum. Of course he learned the story within days of his arrival, and when word came from Cochin the following week that an aged uncle had died, the man hastily resigned and left the city as quickly as possible.

The more difficult the scheme became, the more determined Krishnankutty grew to see it through to a triumphant conclusion. He spared himself a pointless visit to the nervous elders of the Corporation, but with a single-minded zeal he advertised for a contractor from the adjacent state of Tamil Nadu, hired a man and brought him to Trivandrum at his own expense, gathered a completely different set of Harijan labourers, and saw to it that the contractor ate and slept as a guest at his own house, so that he would have little opportunity to talk to local people. And so the work was finished.