Janus (31 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

,

we can hear a note of sharp dissent from the orthodox attitude:

The Origin

of Species

this introduction no longer appears.

Chapter I, 10

, I mentioned the classic example of

the forelimbs of vertebrates which, whether they serve reptiles, birds,

whales or man, show the same basic design of bones, muscles, nerves, etc.,

and are accordingly called homologous organs. The functions of legs,

wings and flippers are quite different, yet they all are variations on

a single theme -- strategic modifications of a pre-existing structure:

the forelimb of the common reptilian ancestor. Once Nature has 'taken

out a patent' on a vital organ, she sticks to it, and that organ becomes

a stable evolutionary holon. Its basic design seems to be governed by

a fixed

evolutionary canon

; while its adaptation to swimming,

walking, or flying is a matter of evolution's flexible

strategy

.

hierarchy, from the sub-cellular level to the primate brain. The same four

chemical bases in the chromosomal nucleic acid -- DNA -- constitute the

four-letter alphabet of the genetic codes throughout the animal kingdom;

the same 'make' of organelles function in their cells; the same chemical

fuel -- ATP -- provides their energy; the same contractile proteins serve

the motions of the amoeba and of human muscles. Animals and plants are

made of homologous molecules, organelles, and even more complex homologous

sub-structures. They are the stable holons in the evolutionary flux,

the nodes on the tree of life.

concerned with the nature of evolutionary

strategies

(Darwinian,

Lamarckian, etc.) which made the higher forms of life branch out of

the roots at the base of the hierarchy. But dazzled by the prodigious

variety

of plants and animals, biologists were inclined to pay less

attention to the

uniformity

of those basic units -- reflected in

the phenomena of homology -- and the

limitations

which it imposed

on all existing and possible forms of life on this planet. After all,

the basic uniformity of the organelles which constitute the living cell

is itself derived from the limitations imposed by the basic chemistry

of organic matter such as amino-acids, proteins, enzymes. On a higher

level,' the genetic micro-hierarchies impose further constraints on

hereditary variations. Still further up the 'great central something'

regulates -- in ways unknown to us -- the 'harmonious coordination' of

genetic changes. Their combined effect is the evolutionary canon, which

permits a great amount of variations, but only in limited directions

on

a limited number of themes

. Evolution is not a free-for-all but -- to

revert to our formula -- a game with fixed rules and flexible strategies,

played over thousands of millennia.

use the example of the Australian marsupials, which I used in

The Ghost

in the Machine

.* I called them an enigma wrapped in a puzzle. The enigma

is shown by the drawings on p. 208. The puzzle is why evolutionists

refuse to see the problems that it poses.

They have evolved, independently from each other, from a common ancestry

(the now extinct therapsids, or mammal-like reptiles). The marsupial

embryo is expelled from the womb in a very immature state of development

and is reared in an elastic pouch attached to the mother's belly. A newborn

kangaroo is a half-finished job: about an inch long, naked, blind,

its hind-legs no more than embryonic buds. One might speculate whether

the human infant, more developed but still helpless at birth, would

be better off in a maternal pouch; one is also reminded of African

or Japanese women carrying their infants strapped to their backs. But

whether the marsupial method is better or worse than the placental, the

point is that they differ. Pouch and placenta might be called variations

in strategy within the general schema of mammalian reproduction.

evolution some time before Australia became separated from the Asiatic

mainland in the late Cretacean. The marsupials (who had branched out from

the common ancestral type earlier than the placentals) got into Australia

before it was cut off; the placentals did not. So the two lines evolved

in complete separation for about a hundred million years. The enigma is

why so many animals in the Australian fauna, produced by the independent

evolutionary line of the marsupials, look so startlingly like their

opposite numbers among placentals. The drawings on p. 208 show on the

left side three specimens of marsupials, on the right the corresponding

placentals. It is as if two artists who have never met and never shared

the same model, had drawn parallel series of almost identical portraits.

managed to get there in time were tiny, mouse-like, pouched animals,

perhaps not unlike the still extant yellow-footed pouched mouse,

but even more primitive. And yet these archaic creatures, confined to

their island continent, branched out and gave rise to pouched versions

of our placental moles, ant-eaters, flying squirrels, cats, wolves,

lions, and so on -- each like a somewhat clumsy copy of its placental

namesake. Why, if evolution were a free-for-all, why did Australia not

produce some entirely different species of animals, like the bug-eyed

monsters of science fiction? The only moderately unorthodox creation of

that isolated island in a hundred million years are the kangaroos and

wallabies; the rest of the fauna consists of rather inferior duplicates

of more efficient placental types -- variations on a limited number of

themes, within the repertory of the evolutionary canon.

offer is summed up in the following quotation from an authoritative

textbook:

the same problem, concludes that the explanation is 'selection of random

mutations'. [2]

that the vague phrase 'preying on animals of approximately the same size

and habits' -- which can be applied to hundreds of different species

-- provides a sufficient explanation for the emergence of the nearly

identical skulls shown on p. 208. Even the evolution of a single species

of wolf by random mutation plus selection presents, as we have seen,

insurmountable difficulties. To

duplicate

this process independently

on island and mainland would mean squaring a miracle. The puzzle remains

why the Darwinians are not puzzled -- or pretend not to be.*

Doppelgängers

lend strong support to

the hypothesis that there are unitary laws underlying evolutionary

diversity, which permit virtually unlimited variations on a limited

number of themes. They include, on the lower levels of the hierarchy,

macromolecules, organelles and cells which represent evolutionary holons;

higher up, homologous organs such as the vertebrate forelimbs, lungs, and

gills, not to mention eyes equipped with lenses -- which have evolved,

independently from each other, several times in evolutionary lines

as far apart as molluscs, spiders and vertebrates. Still higher up we

have to include in the list the more or less standardized vertebrate

types exemplified by the drawings. The 'more or less' we can ascribe to

variations in evolutionary strategy in a changing environment; but their

standardization we can only explain by rules built into the genetic

micro-hierarchies which confine evolutionary advances to certain main

avenues, and filter out the rest.

transcendentalists of the eighteenth century, including Goethe

(and eventually to Plato); but it was revived by a number of modern

evolutionists who toyed with the idea of 'internal selection' without

spelling out its profound implications.* Thus Helen Spurway concluded from

the universal recurrence of homologous forms that the organism has only

'a restricted mutation spectrum' which 'determines its possibilities

of evolution'.

[3]

Other biologists have talked of 'organic

laws co-determining evolution', 'moulding influences guiding evolutionary

change along certain avenues'

[4]

; while Waddington reverted

to 'the notion of archetypes . . . the idea, that is, that there are

only a certain number of basic patterns which organic form can assume'.

[5]

What they are implying (without saying it in as many

words) is that, given the conditions on our particular planet, its

gravity and temperature; the composition of its atmosphere, oceans and

soil; the nature of available energies and raw materials, life from its

inception in the first blob of living slime could only evolve

in a

limited number of directions in a limited number of ways

. But this

in turn implies that just as the basic pattern of the twin wolves was

foreshadowed, or present

in potentia

, in their common ancestry,

so the mammal-like reptile creature must have been potentially present

in the ancestral chordate -- and so on back to the ancestral protist,

and the first self-replicating strand of nucleic acid.

homology -- which Sir Alister Hardy has called 'absolutely fundamental

to what we are talking about when we speak of evolution'.

[6]

If this line of argument is correct, it puts an end to the monsters

of science fiction as possible forms of life on earth -- or on other

planets similar to it. But it does not mean the opposite either:

it emphatically does not mean a rigidly predetermined universe which

unwinds like a mechanical clockwork. It means -- to revert to one of

the leitmotifs of this book -- that the evolution of life is a splendid

game played according to fixed rules which limit its possibilities but

leave sufficient scope for virtually limitless variations. The rules

are inherent in the basic structure of living matter, the variations are

derived from flexible strategies which take advantage of the opportunities

offered by the former.

alone, nor the execution of a rigidly predetermined computer programme.

It could be compared to musical composition of the classical type, whose

possibilities are limited by the rules of harmony and the structure of

the diatonic scales -- which nevertheless permit an inexhaustible number

of original creations. Or it could be compared to a game of chess,

obeying fixed rules with equally inexhaustible variations. And lastly --

to quote from

we can hear a note of sharp dissent from the orthodox attitude:

This situation, where scientific men rally to the defence of a doctrine

they are unable to define scientifically, much less demonstrate with

scientific rigour, attempting to maintain its credit with the public

by the suppression of criticism and the elimination of difficulties,

is abnormal and undesirable in science. [18]

The Origin

of Species

this introduction no longer appears.

Chapter I, 10

, I mentioned the classic example of

the forelimbs of vertebrates which, whether they serve reptiles, birds,

whales or man, show the same basic design of bones, muscles, nerves, etc.,

and are accordingly called homologous organs. The functions of legs,

wings and flippers are quite different, yet they all are variations on

a single theme -- strategic modifications of a pre-existing structure:

the forelimb of the common reptilian ancestor. Once Nature has 'taken

out a patent' on a vital organ, she sticks to it, and that organ becomes

a stable evolutionary holon. Its basic design seems to be governed by

a fixed

evolutionary canon

; while its adaptation to swimming,

walking, or flying is a matter of evolution's flexible

strategy

.

hierarchy, from the sub-cellular level to the primate brain. The same four

chemical bases in the chromosomal nucleic acid -- DNA -- constitute the

four-letter alphabet of the genetic codes throughout the animal kingdom;

the same 'make' of organelles function in their cells; the same chemical

fuel -- ATP -- provides their energy; the same contractile proteins serve

the motions of the amoeba and of human muscles. Animals and plants are

made of homologous molecules, organelles, and even more complex homologous

sub-structures. They are the stable holons in the evolutionary flux,

the nodes on the tree of life.

concerned with the nature of evolutionary

strategies

(Darwinian,

Lamarckian, etc.) which made the higher forms of life branch out of

the roots at the base of the hierarchy. But dazzled by the prodigious

variety

of plants and animals, biologists were inclined to pay less

attention to the

uniformity

of those basic units -- reflected in

the phenomena of homology -- and the

limitations

which it imposed

on all existing and possible forms of life on this planet. After all,

the basic uniformity of the organelles which constitute the living cell

is itself derived from the limitations imposed by the basic chemistry

of organic matter such as amino-acids, proteins, enzymes. On a higher

level,' the genetic micro-hierarchies impose further constraints on

hereditary variations. Still further up the 'great central something'

regulates -- in ways unknown to us -- the 'harmonious coordination' of

genetic changes. Their combined effect is the evolutionary canon, which

permits a great amount of variations, but only in limited directions

on

a limited number of themes

. Evolution is not a free-for-all but -- to

revert to our formula -- a game with fixed rules and flexible strategies,

played over thousands of millennia.

use the example of the Australian marsupials, which I used in

The Ghost

in the Machine

.* I called them an enigma wrapped in a puzzle. The enigma

is shown by the drawings on p. 208. The puzzle is why evolutionists

refuse to see the problems that it poses.

* The section that follows is a compressed version of The Ghost in

the Machine, pp. 143-6.

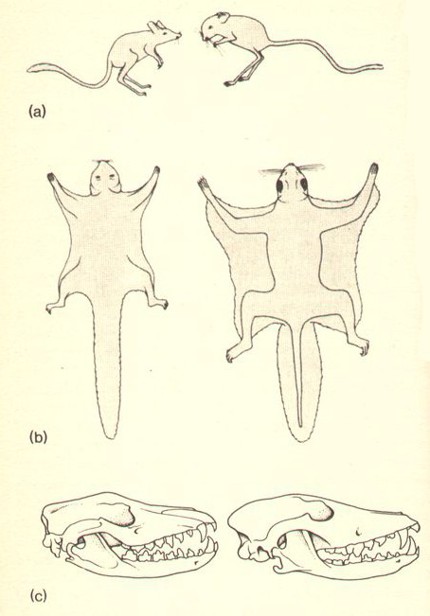

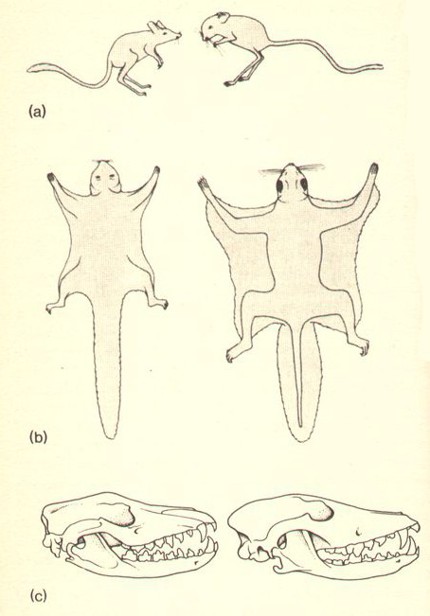

(a) Marsupial jerboa and placental jerboa

(b) Marsupial flying phalanger and placental flying squirrel.

(c) Skull of Tasmanian wolf and skull of placental wolf (after Hardy).

They have evolved, independently from each other, from a common ancestry

(the now extinct therapsids, or mammal-like reptiles). The marsupial

embryo is expelled from the womb in a very immature state of development

and is reared in an elastic pouch attached to the mother's belly. A newborn

kangaroo is a half-finished job: about an inch long, naked, blind,

its hind-legs no more than embryonic buds. One might speculate whether

the human infant, more developed but still helpless at birth, would

be better off in a maternal pouch; one is also reminded of African

or Japanese women carrying their infants strapped to their backs. But

whether the marsupial method is better or worse than the placental, the

point is that they differ. Pouch and placenta might be called variations

in strategy within the general schema of mammalian reproduction.

* Not counting the nearly extinct egg-laying mammals, such as the

duck-billed platypus.

evolution some time before Australia became separated from the Asiatic

mainland in the late Cretacean. The marsupials (who had branched out from

the common ancestral type earlier than the placentals) got into Australia

before it was cut off; the placentals did not. So the two lines evolved

in complete separation for about a hundred million years. The enigma is

why so many animals in the Australian fauna, produced by the independent

evolutionary line of the marsupials, look so startlingly like their

opposite numbers among placentals. The drawings on p. 208 show on the

left side three specimens of marsupials, on the right the corresponding

placentals. It is as if two artists who have never met and never shared

the same model, had drawn parallel series of almost identical portraits.

managed to get there in time were tiny, mouse-like, pouched animals,

perhaps not unlike the still extant yellow-footed pouched mouse,

but even more primitive. And yet these archaic creatures, confined to

their island continent, branched out and gave rise to pouched versions

of our placental moles, ant-eaters, flying squirrels, cats, wolves,

lions, and so on -- each like a somewhat clumsy copy of its placental

namesake. Why, if evolution were a free-for-all, why did Australia not

produce some entirely different species of animals, like the bug-eyed

monsters of science fiction? The only moderately unorthodox creation of

that isolated island in a hundred million years are the kangaroos and

wallabies; the rest of the fauna consists of rather inferior duplicates

of more efficient placental types -- variations on a limited number of

themes, within the repertory of the evolutionary canon.

offer is summed up in the following quotation from an authoritative

textbook:

Tasmanian [i.e., marsupial] and true wolves are both running predators,

preying on other animals of about the same size and habits. Adaptive

similarity [i.e., adaptation to similar environments] involves

similarity also of structure and function. The mechanism of such

evolution is natural selection. [1]

the same problem, concludes that the explanation is 'selection of random

mutations'. [2]

that the vague phrase 'preying on animals of approximately the same size

and habits' -- which can be applied to hundreds of different species

-- provides a sufficient explanation for the emergence of the nearly

identical skulls shown on p. 208. Even the evolution of a single species

of wolf by random mutation plus selection presents, as we have seen,

insurmountable difficulties. To

duplicate

this process independently

on island and mainland would mean squaring a miracle. The puzzle remains

why the Darwinians are not puzzled -- or pretend not to be.*

* Various terms have been invented to describe this phenomenon such as

'convergence', 'parallelism', 'homeoplasy', but these are purely

descriptive, without explanatory value.

Doppelgängers

lend strong support to

the hypothesis that there are unitary laws underlying evolutionary

diversity, which permit virtually unlimited variations on a limited

number of themes. They include, on the lower levels of the hierarchy,

macromolecules, organelles and cells which represent evolutionary holons;

higher up, homologous organs such as the vertebrate forelimbs, lungs, and

gills, not to mention eyes equipped with lenses -- which have evolved,

independently from each other, several times in evolutionary lines

as far apart as molluscs, spiders and vertebrates. Still higher up we

have to include in the list the more or less standardized vertebrate

types exemplified by the drawings. The 'more or less' we can ascribe to

variations in evolutionary strategy in a changing environment; but their

standardization we can only explain by rules built into the genetic

micro-hierarchies which confine evolutionary advances to certain main

avenues, and filter out the rest.

transcendentalists of the eighteenth century, including Goethe

(and eventually to Plato); but it was revived by a number of modern

evolutionists who toyed with the idea of 'internal selection' without

spelling out its profound implications.* Thus Helen Spurway concluded from

the universal recurrence of homologous forms that the organism has only

'a restricted mutation spectrum' which 'determines its possibilities

of evolution'.

[3]

Other biologists have talked of 'organic

laws co-determining evolution', 'moulding influences guiding evolutionary

change along certain avenues'

[4]

; while Waddington reverted

to 'the notion of archetypes . . . the idea, that is, that there are

only a certain number of basic patterns which organic form can assume'.

[5]

What they are implying (without saying it in as many

words) is that, given the conditions on our particular planet, its

gravity and temperature; the composition of its atmosphere, oceans and

soil; the nature of available energies and raw materials, life from its

inception in the first blob of living slime could only evolve

in a

limited number of directions in a limited number of ways

. But this

in turn implies that just as the basic pattern of the twin wolves was

foreshadowed, or present

in potentia

, in their common ancestry,

so the mammal-like reptile creature must have been potentially present

in the ancestral chordate -- and so on back to the ancestral protist,

and the first self-replicating strand of nucleic acid.

* See above, Ch. IX, 7. For an excellent short

critical discussion see L. L. Whyte's Internal Factors in

Evolution and W. H. Thorpe's review of the book in Nature,

14 May, 1966.

homology -- which Sir Alister Hardy has called 'absolutely fundamental

to what we are talking about when we speak of evolution'.

[6]

If this line of argument is correct, it puts an end to the monsters

of science fiction as possible forms of life on earth -- or on other

planets similar to it. But it does not mean the opposite either:

it emphatically does not mean a rigidly predetermined universe which

unwinds like a mechanical clockwork. It means -- to revert to one of

the leitmotifs of this book -- that the evolution of life is a splendid

game played according to fixed rules which limit its possibilities but

leave sufficient scope for virtually limitless variations. The rules

are inherent in the basic structure of living matter, the variations are

derived from flexible strategies which take advantage of the opportunities

offered by the former.

alone, nor the execution of a rigidly predetermined computer programme.

It could be compared to musical composition of the classical type, whose

possibilities are limited by the rules of harmony and the structure of

the diatonic scales -- which nevertheless permit an inexhaustible number

of original creations. Or it could be compared to a game of chess,

obeying fixed rules with equally inexhaustible variations. And lastly --

to quote from

Other books

Repairman Jack [07]-Gateways by F. Paul Wilson

Under Cover of Daylight by James W. Hall

Listed: Volume III by Noelle Adams

Steam (Legends Saga Book 3) by Stacey Rourke

Miss Cresswell's London Triumph by Evelyn Richardson

NaGeira by Paul Butler

The First 90 Days by Michael Watkins

Fall of a Philanderer by Carola Dunn

Head Full of Mountains by Brent Hayward