Jeanne Dugas of Acadia (18 page)

Read Jeanne Dugas of Acadia Online

Authors: Cassie Deveaux Cohoon

Part 4

Capture and

Imprisonment

Chapter 35

T

he spring of 176l arrived quietly in Nipisiguit with gentle weather, almost as if it sensed that it must not draw attention to itself or its refugees. Charles and Anne took their family back to their house in Caraquet. Abraham and Marguerite stayed on to help Joseph's family, who were to share their schooner with Abraham. There was an attempt among the women to think in terms of a normal life, and Jeanne and the others scrounged whatever seeds and cuttings they could to start their kitchen gardens. There was no evidence of new supplies, though Jeanne was not aware of any privateering activity. The winter had been difficult, but no one had died of starvation. They had all survived, or rather endured.

â

Alexander Murray, the British governor of Québec, was angry because some of the Acadian privateers along the North Shore had continued their activities even after their defeat at the Ristigouche Poste and the destruction of La Petite Rochelle. He was determined that an end should be put to these raids. In April, he wrote to Colonel Amherst: “Now is the time to evacuate that country entirely of the neutral French and to make the Indians of it our own.”

In early July he authorized Pierre du Calvet, the former storekeeper at Ristigouche Poste, to take a census of all the Acadian refugees remaining on the North Shore and to determine the number of extra ships needed to transport them to Québec.

Du Calvet arrived in the area on the sloop

Sainte-Anne

later in July, bearing his instructions. Despite his earlier betrayal, the refugees welcomed du Calvet among them. The idea of a census was not so threatening. At least it recognized their existence and appeared to place them under Québec's jurisdiction.

There was, of course, much discussion and arguing. Not everyone trusted du Calvet, especially Joseph Dugas, but what choice did they have? Very few of the refugees wanted to go to Québec, and they had learned from experience that if they could stall long enough they might be left in place. The former storekeeper spent more than two months travelling from one settlement to the other and left with a very thorough list of the refugees, their locations and their ships.

There was an easing of tensions after du Calvet's departure. They were living as if they were no longer under siege. People walked boldly along the shore, their ships sailed freely between their settlements, and Acadian voices were raised loud again, whether in argument or laughter or song. The children, taking their cue from their elders, ran about and played with abandon. The only real worry Jeanne had concerned her brother Charles. After a recent visit to him in Caraquet, Joseph reported that Charles was sick. She thought of asking Pierre to take her to see him, but she knew that Anne was more than capable of looking after him.

The autumn weather was kind to them again and gave its own beauty to the area. Jeanne was not sure which she preferred, the vibrant autumn colours or the sweet green of spring. Both filled her with a simple joy. She counted her blessings. They had a home and were looking forward to an easier winter than the last, thanks to their hard work during the summer.

â

In November, disaster struck.

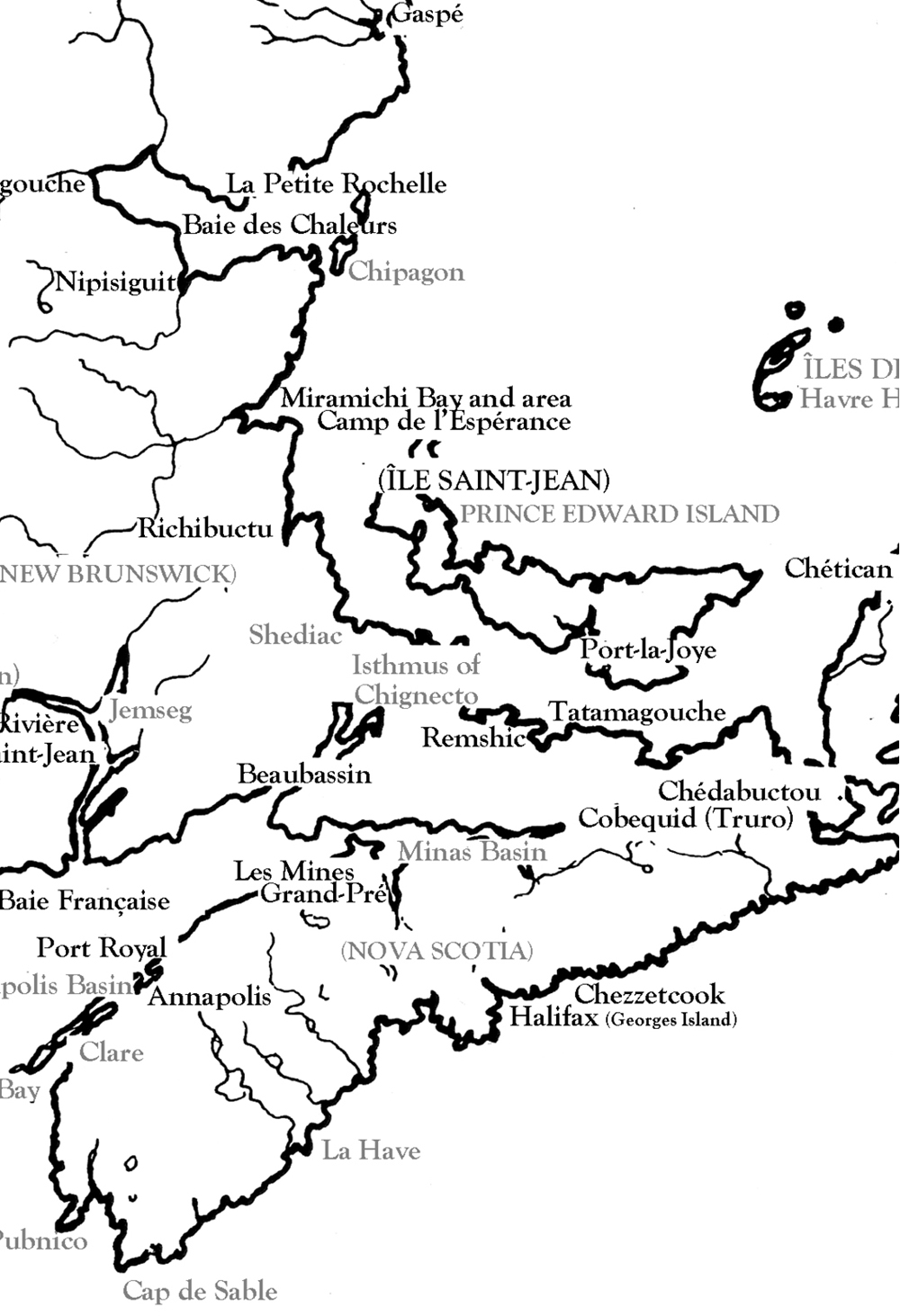

Three British warships arrived led by Captain Roderick MacKenzie and a company of about fifty Highlanders. They were guided by Ãtienne Echbock, chief of the Mi'kmaq at Pokemouche, one of the districts that had made a peace agreement with the British. Pierre du Calvet's census had been ordered by the Governor of Québec, but MacKenzie's orders came from Colonel Forster, commander of the British troops in Nova Scotia. MacKenzie had orders to capture all the Acadians in the Baie des Chaleurs and Miramichi areas.

Captain MacKenzie arrived first at Nipisiguit, rousing Jeanne from her reverie on the beauty of the land. She had turned to look to the sea and was shocked to see a band of men in British military dress marching up from the beach with muskets at the ready. They came right to her. Her neighbours stood watching, some of the hardier among them coming to stand with her. The militia had now started to move to surround them, and a French-speaking militiaman addressed them.

“Mesdames, Messieurs. I speak on behalf of Captain Roderick MacKenzie. You are hereby ordered, by the commander of the troops of the British king in Nova Scotia, to come with us. You may bring a small bundle of personal effects with you.”

“But Monsieur,” said René Gaudet, one of the few men present, “you must explain to us why this is happening. We have given a census to the governor of Québec and therefore we come under Québec's jurisdiction. Not Nova Scotia's.”

The young militiaman snorted. “Well, it does not much matter, does it? Come on, move. If you resist we will have to kill you. And don't think you can escape into the woods.”

How could such a dreadful thing happen on such a beautiful day? Jeanne ran to gather her children and to warn the others, while she tried to think calmly. She told the other women that she thought it was all a mistake and that when their husbands could speak to these men and explain about the census they would be released. She quickly made several bundles, each with a change of clothes, extra moccasins, bits of food, a blanket. To her own bundle, she added the statuette of Sainte-Anne and the shawl.

“Tell me what to do, Maman,” begged Marie. “I can help.”

“Keep an eye on your two brothers and your sister, Marie, promise me?”

“Yes, Maman.”

Small groups of women and children started to gather on the beach. Jeanne kept an eye out for Marguerite and her children and Joseph's children.

MacKenzie and his militiaman came back to Jeanne.

“Where are the ships, Madame?”

“The men have taken them out.”

“All of them?”

“I'm not sure, Monsieur.”

“Where do they keep them?”

“Here, or up the rivière Nipisiguit.”

Jeanne was aware that René Gaudet was trying to catch her eye, but she avoided looking at him. Please don't make things worse, she tried to silently warn him.

MacKenzie turned to his aide. “We'll have to put these people in the hold of our ship,” he said reluctantly. “Go to it.”

“The men have found two families. One has a very sick elderly man and the other a woman about to give birth. What do we do with them?”

“Damnation!

Leave them. And one of the women to look after them, but not someone capable of running to give the alarm.”

“Sir!”

“Do you women know where your men are? We know a number of Acadian resisters who have been harassing British ships are based here. Where are these men?”

Jeanne replied, “They could be anywhere, Monsieur, we have no way of knowing.” This was, after all the truth.

The refugee women and children were roughly pushed down to the shore, taken out by

shallop to the British ships, and packed into dark, dirty, smelly holds.

Chapter 36

C

aptain Roderick MacKenzie and his Highlanders proceeded to capture Acadian refugees at Caraquet, Chipagan, Ristigouche, and all the other places listed in du Calvet's census. A few places managed to hear the news before their arrival and families were able to flee into the forest. When MacKenzie arrived at Néguac, they found the village abandoned. In all, they captured almost eight hundred prisoners â men, women and children â and thirteen ships.

In the end, MacKenzie could not take all the captured Acadians with him, but he made sure that he had the key troublemakers, men like Joseph Leblanc dit Le Maigre and his son Paul, whose ships were armed and equipped for privateering. Charles Dugas, because he was ill, was not taken prisoner. He remained in Caraquet with Anne and their children.

MacKenzie left with more than three hundred men, women and children packed into three warships and about half of the captured Acadian ships. The Acadian men who were allowed to sail their own ships with one or two Highlanders on board knew that their families were being held hostage in the holds of the British ships. The unused Acadian ships were destroyed or burned, as were the houses and equipment. Supplies were confiscated. Stocks of dried fish and even household furniture and other items were taken. Acadian refugees left behind would have no means to travel and would face a very difficult fight for survival in the coming winter.

Chapter 37

I

n the hold of the ship carrying Jeanne and Marguerite, the prisoners fell silent when they sensed they were headed out to sea. Even the children stopped asking questions their mothers could not answer. Their captors had not told them where they were going or what would happen to them. Were they being taken somewhere in Nova Scotia? Were they being deported? Had their husbands been captured too? After a few hours at sea, a crewman brought them some water to drink, but no food. They plied him with questions, but he said not a word.

The hopes that Jeanne had pinned on the census and Québec quickly disappeared. There was no evidence that an error had been made. What would happen to them now? Would they be reunited with their husbands? Jeanne and Marguerite did not need to remind each other of the stories of families torn apart during the deportations in 1755 and 1758. Jeanne could feel the outline of Sainte-Anne in her bundle and she kept one hand on the statuette in a desperate plea for her help.

It was getting dark when they made land, they knew not where. Hungry, tired and apprehensive, they were grateful to at least be out of the hold of the ship and able to breathe clean air again. Some of the children had slept, but now they were fussing and upset.

Men were waiting for them with torches to light their way. René Gaudet asked one of them where they were.

“Fort Cumberland,” was the curt answer.

“Have any other prisoners been taken here from the Baie des Chaleurs?”

“Some. Come on now, move!”

René Gaudet walked beside Jeanne. “This is Beauséjour,” he said. Seeing Jeanne's pale, stricken face, he added, “I'm sure they must have brought the others here.”

They were quickly shuffled into casements and underground storage rooms with dirt floors. Clearly, these buildings were not meant to be used as a prison. As they entered they were handed a piece of black bread for each family member and one jug of water for the family group. There was no way to tell if any other families or husbands had arrived before them.

Early the following morning they were taken outside into an open area to join the other refugees taken prisoner at the Baie des Chaleurs and the Miramichi. Captain MacKenzie was there and the group was under heavy guard. There were tears of joy and relief when families were reunited.

Pierre had all four children clinging to him, and Nono tried to give him the bit of bread he had left. “No, Nono, you have to eat it, so you can grow up to be big and strong and help Papa,” Pierre told him. The boy needed no further prompting and ate it hungrily.

An aide of Captain MacKenzie's announced that they were to be taken to Halifax to await deportation. They would sail there in British ships in several stages. Their own ships were confiscated. They would be permitted to leave in family groups. He proceeded to read a list of names of men who would be the first to go, including Joseph Dugas, Abraham Dugas, Joseph Leblanc dit Le Maigre and others. “You will leave today.”

These men were all well-known resistance leaders and privateers. Pierre Bois's name was not on the list. Jeanne didn't know if this was a good or a bad thing, but it meant that Marguerite, her children and Joseph's children would go with Abraham.

Joseph started to approach Jeanne, but a guard stopped him. “I just want a word with my sister,” Joseph said, and at a nod from Captain MacKenzie, he was allowed to go to her.

Joseph's face looked thunderous. He took her arm and drew her a bit away from the others. The children stayed with Pierre.

“What's happening, Joseph?”

“What's happening? We were betrayed again, Jeanne. And again by Pierre du Calvet, a man who was supposed to be on our side.” He shuddered with suppressed anger.

“Jeanne, there is not much time and there is something I must tell you.”

“Yes?”

“It's about Martin. Your friend Martin.” He hesitated.

“You've seen him?” She was trying to think why Joseph found it difficult to give her news of Martin. “Has his group signed a peace treaty with the British?” she asked.

“No. He was still fighting the British.” Joseph paused.

“Jeanne,” he said slowly, “Martin was killed in a skirmish with them. I'm very sorry to have to tell you about this.” He reached into his coat and brought out a slim pouch made of woven grass. “Martin had this on him. I thought you would like to have it back.”

Ah, mon Dieu! She stood in front of Joseph, the colour draining from her face. Martin, dead? Her lips trembled but she could not let herself cry.

Joseph pushed the keepsake toward her. “Take this, Jeanne. It's the portrait of you in your blue silk gown.” She swayed. He grabbed her arms to steady her.

“Jeanne, Martin was a wonderful man. I loved him like a brother. But now we have to go on without him. Jeanne! Are you listening to me?” He paused. “He had a wife and children. Did you know that?”

She closed her eyes so that Joseph could not see into her soul. In truth, she had not known, but it would not have changed how she felt about Martin. She opened her eyes and looked at Joseph. “I have a family too,” she said softly.

“Yes, you do.”

Joseph wrapped his arms around her. “I'm so sorry, Jeanne. We'll see you at Halifax. I don't see how we can be deported before the spring. Take care of Pierre. He's a good man too.”

She could only nod in reply.

Jeanne, Pierre and their children were in the last group and sailed two days later. They arrived at the prison on Georges Island in Halifax Harbour on a cold and wet fall day to find the prison sheds allocated to the Acadians already filled to overflowing. They spent their first few nights there sleeping in the rough on wet, muddy, cold ground. They were given rations too meagre to satisfy hunger and filthy blankets too threadbare to provide warmth.