Jellied Eels and Zeppelins (2 page)

Ethel’s father, mother and sister Florrie

One particular occasion that Ethel remembers well, was when her elder sister, Florrie had been misbehaving all day:

‘Mum told her to go along to the local hardware store, to buy a cane. The first time Florrie returned with a bundle of wood for lighting the fire. Mum sent her back again. This time, naughty Florrie had bought candles, so Mum ordered her to return to the shop. On the third occasion, my sister had bought the cane and Mum hung it over the line above the fireplace, telling her that if she misbehaved again, she’d get the cane across her legs. When Dad came home and saw it, he was furious. He grabbed it and whacked it behind Mum’s ankles telling her sternly: ‘Does that hurt? Now you know what it feels like. Don’t ever let me see you hitting those children!’ Then he broke the cane in half and threw it away.

That was the only time I ever saw him hit my Mum. He didn’t believe in hitting women. He reckoned it was disgusting. But he done that on her legs to prove to her how much it hurt - what it felt like. She weren’t allowed to smack us, but my sister used to say, when my mum gave her a wallop now and again, ‘cos she was a little devil, ‘I’ll tell Dad!’

Dad was a complex character. He never saw us kids go without anything. He was good - we never had no luxuries, just the bare things. My Dad always used to provide us with food, clothing and shoe leather. He made sure we never had wet feet and that there was food in our bellies. That’s what I mean when I say he was a good dad. He brought us up well, I must say that. We never had no luxuries of any sort - no sweets or anything, only when he started working at Lonco, then we used to get his free samples.’

Edwin also insisted on good manners at the dinner table.

‘We used to have to sit with our elbows in plates for one hour if we were caught with them on the table.’

The children were also never allowed to ask for anything - they had to wait to be offered

.

Edwin (right), standing in front of his ‘Lonco’ van

Working as a parcel delivery man for Lipton’s-owned Lonco, Mr Turner would sometimes bring home sweet samples. On one occasion, he had with him a small box of chocolates:

Florrie‘Father offered us one each. He then offered Florrie another but not me. The next day when he was out, I decided to help myself to a chocolate. In the evening, we went to a relative’s for tea. Just before we sat down, Father told us all to be quiet. He said that we had a thief among us - someone had stolen one of his chocolates.

Well, I realised that he knew it was me, so I shot under the table and that’s where I stayed for the rest of the evening!’

Naturally, the feeling that Florrie was her father’s favourite, caused many problems between the two girls and there were the inevitable fights:

‘I used to have lots of little bruises where Florrie pinched me in the bed we shared.’

Ethel’s sister also once hit her with a stick because she refused to do the washing up when it wasn’t her turn.

Another fracas occurred one Sunday afternoon, when their father asked the two girls to go to Pops, the local publican:

‘You used to get allowed so much beer free and, as we had a relation of ours coming from Blackfriars, my Dad said to my sister and me ‘Take these two pint bottles up to Pops and get them filled up with beer’… Well, this day - it was a Sunday afternoon - we had a pint bottle each to carry up Coppermill Lane to get them filled up. We were halfway up the road, near the school, when my sister said ‘You can take the two bottles and bring them back!’ I thought ‘Why should I?’ so I put my bottle on the floor and said ‘I’m not taking it!’ She said ‘You pick that up or I’ll give you one!’ So I picked it up and knocked her on the head with it! It was a glass bottle and she went crying all the way down the road to tell Mum and Dad. I followed her. They told me to take the two bottles back up the road and get them both filled up with beer. You always get what’s coming to you.’

Ethel’s father also liked to keep up appearances when the family went out together as he was a very proud man:

‘My Dad used to take us round to relations of ours just for a little walk when we came back from Sunday School. We used to have a cup of tea and then come back for our dinner. Dad used to walk behind us and say ‘Hold your shoulders up, walk in line with the pavement!’ He used to pull our shoulders back if we didn’t do it. We used to get away with it a little bit with my mother, but not with my Dad. He made sure that we kept our feet straight, so that we didn’t get pigeon-toed. ‘Look at yourself in the shop window!’ he used to say. And, after that, we used to look in the shop windows, even when we were out on our own.

Dad wouldn’t let us read the newspapers, but, when Emily Davison threw herself in front of the King’s horse at the Derby in 1913, Dad showed us the paper. He said ‘See that. That’s the sort of thing that happens when you try and control something.’(I think what he meant by ‘control’ you see, was that they was trying to control the Government). He reckoned that it was clever. He agreed with women getting the vote. He reckoned it was fair for the woman with the position she had in a man’s house, to have the vote as well. He really believed in it.’

An Act in 1918 allowed women of 30 and over, married to a property owner, or property owners themselves, to vote in elections. It wasn’t until 1928 that there was full equality, when all women over 21 were given the vote.

‘Mum was quite thrilled to be able to vote. I’ll tell you what my Mum used to do - I remember seeing her do it when I was a kid. She and her women friends, ‘cos they were in the Labour Movement too, used to pull our Labour MP’s cart up the road with him sitting in it! His name was Valentine La Touche McEntee and he was a lovely man, very helpful. You could go and talk to him. Mum was very, very keen to get the vote and never missed the chance to.

The first time I voted, I remember saying how proud I was. It was a funny feeling, when I think of it. I felt very grown up.

Some of the women were very oppressed in my day and age, especially when a lot of men were knocking them about as they used to. A lot of it went on behind closed doors. My Dad didn’t beat up my mother. He didn’t smack us either. He didn’t believe in it.’

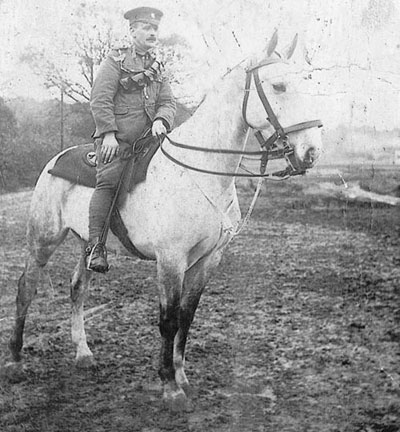

1915-16: Ethel Elvin’s father as a military policeman in Guernsey, astride his mount ‘dolly’

Busbies, Prawns and Bing, Bing, Bing!

‘My Dad was born in May 1884 and my Mum in April of the same year. Dad was the youngest of six, three boys and three girls, but the girls all died within three weeks of each other from diphtheria or scarlet fever when my father was two years old and his mother went on the drink. She came from Ireland. My grandfather used to go looking for her… she used to leave my Dad outside the pub. Then she suddenly disappeared and left him with three boys. That’s why my Dad wouldn’t often touch none of it (

drink

).’

Edwin’s mother was eventually tracked down to Bethnal Green, but it was left to his wheelwright father, Charlie and his cousin, Polly from Maldon, to raise the three boys:

‘The one I used to call Gran, or Aunt Polly, was a cousin of my grandfather’s. She lived at Maldon and she’d just lost her husband. She was only a young woman and she came to look after the boys. Aunt Polly used to cook for my grandfather. My Mum used to say ‘You’ve got two grans,’ and I could never understand why. Aunt Polly - oh, she was really lovely, the sweetest old lady you could ever wish to meet, she was.’

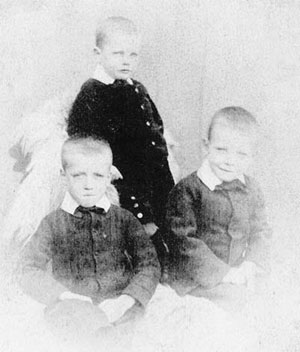

Edwin (rear) with his two brothers. About 1890

Edwin Turner joined the army aged 17 during the Boer War, though he never saw active service:

‘He used to wear a big hat on sideways - like they did in the Boer War. He also wore a busby and that was when it was real fur. It made a dent on Dad’s nose, ‘cos it was so heavy. He stood on guard when Queen Victoria died and he said that they had to stand still for four hours then. He said that the soldiers dropped down like ninepins and they weren’t allowed to touch ‘em - they had to leave them there. But my Dad stood rock still the whole time.’

Edwin first met Ethel’s mother, Florence or Floss, as she was known, when they were at school together. Floss, the youngest of four children, was raised by her older sister, Alma, when their mother was admitted into a sanatorium after her son died from a brain disorder aged just two.

‘My Mum had brown eyes and lovely long black hair. I was told that her father was foreign and that he looked Spanish. He had curly black hair, a curly moustache and curly sideboards. When she was 17, my mother worked as a barmaid in the East End, often working until two in the morning. She couldn’t keep her flat going and, as she had to start work at five in the morning, she slept in a bath at the pub. Dad took her away and married her to stop her from getting tuberculosis!

(The couple married in 1905)

.

Ethel’s paternal grandfather Charlie, whom she adored

My Dad very rarely drank, but, when he did, he’d only have two pints and it made him happy, ‘cos he wasn’t used to it. He came home from work one day and he was supposed to have come home mid afternoon on Saturdays for Mum to have been able to go shopping. This was just after the first war when he used to drive around London, taking stuff to the docks. He met a lot of friends from his old firm and he went out with them and didn’t come back ‘til 10. We were all sitting round, we’d just had a cup of cocoa, I’ll never forget it as long as I live. Mum couldn’t get any groceries, ‘cos she didn’t have no money and the next day was Sunday. There was my sister and her friend Edie and me and another friend of hers, I was about 14 then I think, and Dad came in. He always used to hang his coat on the kitchen door and, as my Mum took the cups out into the kitchenette to wash them up, she said ‘There’s something wrong with your father - sounds as if he’s wobbling.’

Dad came into the room, took out a brown paper bag and put it on the table. ‘I’ve brought you some prawns,’ he said to my Mum. She came in and said ‘You’re drunk.’ ‘No, I’m not,’ said Dad in a slurred voice. Mum said ‘There’s something wrong with you. There’s me waiting for some money to go and get some food and tomorrow’s Sunday - there won’t be any shops open.’ ‘Oh,’ he said and, as he was hanging his coat up, Mum got the tablecloth and - I’ve never forgotten it - we had this big black range you know, and she shook the tablecloth in the range with the prawn bag on it and then she went back out into the kitchenette with the rest of the cups!