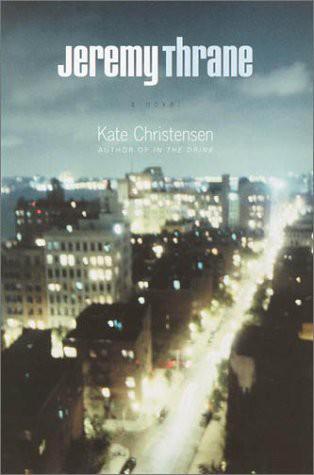

Jeremy Thrane

Authors: Kate Christensen

Tags: #Psychological, #Fiction, #General, #Psychological Fiction, #Gay, #Gay Men, #Novelists, #New York (N.Y.), #Science Fiction, #Socialites, #Authorship

Acclaim for Kate Christensen’s

JEREMY THRANE

“Delightfully droll and astute.”

—The Hartford Courant

“The genre of gay male fiction often serves up amusing but shallow stereotypes, but in this insightful, beautifully written novel, Christensen has created a unique, fully formed, and flawed but likable man.”

—Booklist

“Everybody knows a Jeremy Thrane, but only Kate Christensen has the explosive talent to put his hilarious, wry voice into a sparkling, witty, and smart prose that surprises on every page.”

—Jenny McPhee, author of

The Center of Things

“This is not just another tale about a big-city singleton desperate for a serious relationship; it’s about how we go on living, adapting, and working even after our whole world has changed.”

—Library Journal

“A knockout sophomore effort.… Christensen’s sumptuous prose is both wicked and wise, resulting in a smart, sassy urban tale.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Beneath the book’s sharp satiric surface lies a depth of compassion that raises it far above most contemporary novels. Christensen’s is an astonishing voice.”

—Henry Flesh, Lambda Literary Award–winning author of

Michael

KATE CHRISTENSEN

JEREMY THRANE

Kate Christensen is the author of the novel

In the Drink

. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

ALSO BY KATE CHRISTENSEN

IN THE DRINK

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, JUNE 2002

Copyright © 2001 by Kate Christensen

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2001.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the Broadway edition as follows:

Christensen, Kate, 1962–

Jeremy Thrane: a novel / by Kate Christensen.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction. 2. Fiction—Authorship—Fiction. 3. Socialites—Fiction. 4. Novelists—Fiction. 5. Gay men—Fiction. I. Title

PS3553.H716 J4 2001

813′.54—dc21

2001025547

Permissions credits for

Jeremy Thrane

appear on

this page

.

eISBN: 978-0-307-80738-0

v3.1

FOR THE PUSCH GIRLS

|

ROLLING HOME

I stood alone at the front of the boat. The deck sloped away from me, running with dew. The ferry’s prow split the water into two clean lines of white froth as it plowed its way across New York Harbor, that grand old decaying basin rucked up with centuries of tides and traffic. As the wind, smelling of brine and diesel, lifted my hair from my forehead, I felt like the klieg-lit male lead in an old MGM musical, about to burst forth in a full-throttle tenor. Straight ahead, the Twin Towers’ tops vanished into grizzled clouds. Off to the left was the Statue of Liberty, green as a garden gnome, and beyond, the improbably beautiful industrial banks of New Jersey: O brave old world, that had such smokestacks in it.

It was seven thirty-eight according to the radioactive little numbers on my wrist. I’d left Frankie splayed naked in the sheets, lying on his stomach with his shoulder blades folded together and his arms above his head, sucking a bit of pillowcase into his open mouth as he inhaled, wafting it back out again on the exhale. He hadn’t been so beautiful awake, he’d been a wiry, unprofessional, foul-mouthed waiter. He was a complete stranger to me, and I to him. He’d waited on my friend Max and me the night before in a little Italian place on Carmine Street. It had been a nice job cracking him in two and showing him what was what. He’d put up a gratifying struggle. He was a bantamweight, but he was slippery and fast. Toward dawn I’d pinned him, then let him go to sleep and lay there watching him, listening to the mice in the walls, squinting in the glare of the bulb of his closet. He’d brought me to his house, entangled his body with mine. Now he slept peacefully, having allowed me to ravish him. Was it my low-key manner? The fact that

I’d put on a condom without being asked? But for all he knew, I was a mild-mannered, condom-wearing serial murderer. I wanted to shake him awake and warn him: Next time he might not be so lucky.

Instead, I got up and dressed, let myself out into the heavy, fresh morning air. The sidewalks were broad and cracked; the trees hung low overhead. I walked through a moist, spooky tunnel smelling of moss and water with a greenish light, like a dream, then hiked all the way down a long, sloping strip-mall-covered avenue to Bay Street. I must have unconsciously charted the landmarks and directions of our stumbling journey last night to Frankie’s lair; retracing it, alone and in reverse, I found the vast gray empty ferry terminal and boarded the boat waiting there.

On a bench just inside the ferry’s cavernous cabin slept a fat but frail old woman with her head wrapped in a dirty white bandage or turban, her belongings in bags under the bench. Her face was as purely beautiful in sleep as Frankie’s had been, leathery and weary, but free of the disfigurements of dementia, mood, hunger, calculation. I could smell her. She reeked from stewing in her own animal juices day after day, eating garbage, drinking rotgut. I was sure if she awoke and caught me looking at her, she’d fix me in a hostile glare, but for now she was a sleeping beauty, sad but serene.

The towers of the financial district grew slowly until they loomed ahead, a forest of silent giants bigger than redwoods, denser than cliffs. A crowd gathered at the closed gates on the deck, waiting to be let onto solid ground. I felt them all around me, mild and still half asleep, heard their soft morning breathing, gentle as cows waiting for the farmer to open the pasture gates. I’d always felt an impersonal, brusque fondness for the fellow travelers I brushed up against on my way somewhere, strangers who neither got in my way nor let me get in theirs, all of us suspended together between past and future in a temporal tunnel of watery-green privacy like this morning’s sidewalks. The ship docked with a thud and a grinding of underwater gears, a creak of the gangplank.

I walked out of the huge, echoing South Ferry terminal and headed up Whitehall Street. I caught pleasurable whiffs every now and then, the funky residue of Frankie wafting on gusts of warm air from inside my clothes. After several blocks, Whitehall became Broadway. The statue of

a huge bull pawed at an island in the middle of the street. I crossed over to inspect it, and without thinking, reached down to cup its testicles. Giving them a gentle squeeze, schoolboy hilarity bubbled up in my chest. As I looked uptown with the bull’s balls in my hand, the voice in my head sang “New York, New York, it’s a wonderful town; the Bronx is up and the Battery’s down—” After all these years, I could still be amazed by the cityscape on a fall morning, bronze testicles, skyscrapers, and blowing trash. The autumn air, whether cloudy or clear, had a quality that was present at no other time of year; in the fall, other New Yorks, past and future, real and imaginary, seemed to quiver just beyond the brink of the visible one. Other people’s memories haunted me on every corner, as palpable as my own skin as I passed through them. A yellow cab slid by; its funhouse-like reflection smeared the green glass skin of one building, swelling then compressing to a vanishing blip.

O brave old world. Craning my neck like a tourist, I looked up the side of a skyscraper, straight up its ramrod-sheer belly. I’d never worked in an office. Most of my knowledge of offices came from sitcoms or movies. I thought of them as places where cadres of men with gym-cut muscles under Oxford shirts engaged in homoerotic banter; I imagined corporate men’s rooms as the settings for rushed, silent, half-brutal encounters, a sullen mailroom boy collared in the hallway by an Armani-clad V.P., ordered to step into the gleaming empty room and stand against the wall with his hands splayed against the tiles. The image of the boy’s tight khakis pulled down just far enough to cup his buttocks made me dizzy.

I found with my fingertips in my pants pocket a restaurant mint from last night, a small, pillowy square I fished out and sucked on. It crumbled chalkily on my tongue. I’d heard these mints were soaked in uric acid from patrons who didn’t wash their hands after peeing, then scrabbled their fingers around the mint bowl. But urine was sterile, and anyway I’d always been clinically objective or, rather, cavalierly unconcerned about such things. You could go through life wiping every doorknob with a handkerchief and get picked off by a commonplace flu at fifty, or you could let all microbes take their best shots, thereby strengthening your resistance to them. I opted for the latter strategy, and as a backup maintained a steady level of alcohol molecules to confuse any

invading bugs, in hopes that they would wander through my body’s corridors like locked-out hotel guests, too blotto to find my cells.

It dawned on me then that I was ravenous and caffeine depleted. No wonder I was dizzy. Directly ahead lay an open deli, a bright little trading post on the canyon floor. I ducked in and loitered through the aisles for a moment until a small knot of people in suits at the counter concluded their business and cleared off. I breathed in the smells of Pine Sol, stewing coffee, and hot grease, glanced idly at boxes of prunes and instant chicken noodle soup. When I stepped up to the counter and ordered my breakfast, the counterman immediately handed me a cup of coffee. One of the things I deeply treasured about this city was the fact that people behind counters moved at least three times faster here than anywhere else in the country. The farther outside of Manhattan you got, the longer you had to wait in line; someone somewhere had probably figured out an algorithmic equation to express the exact ratios.