Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle (2 page)

Read Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle Online

Authors: Jerry Langton

Okay, so he's Mike. Cool. They complained to me about waiting for a waitress. I pointed out that they could wait all they like, but no waitress would ever come out of the cafeteria. We agreed to go to the nicer restaurant next door.

We sat. There was silence. I gestured at Parente's ball cap. “Redskins fan?” I asked him.

He nodded.

“Why?” I asked. “Jack Kent Cooke?” It was a strange gambit, but over the years I have met three people from Hamilton who became Washington fans because Cooke, their longtime owner, was a self-made billionaire from their hometown.

Mario laughed. “Nah, it goes back to John Riggins and those guys.” I noted that the only guy he mentioned was the NFL's last great white halfback, and that he mispronounced the name Riggins “Reagan.” I told him I'm a Colts fan. He said that's an easy pick because they always win. I told him that I've been a Colts fan for more than 30 years and had seen my share of 1-15 and 2-14 seasons. He commiserated. I was beginning to like him already.

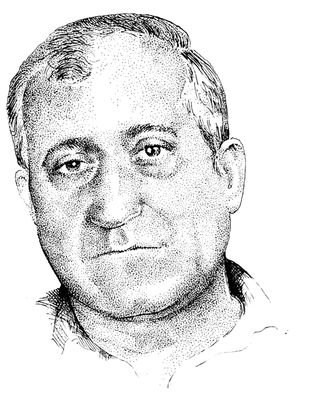

When he took his hat off, I finally got a good look at Parente. His face kind of looked like Joe Pesci's, and he gave off a similar but far less unctuous vibe. He had very dark brown eyes that indicated a depth of intelligence. His head was shaved, but he had a thick, short, whitish-gray beard that started at his cheekbones. It was augmented by a longer, thicker Fu Man-chu mustache of the same color. The line of his nose was an elongated

S

, indicating multiple breakages. I looked closely at both of his eyes, because I had heard he'd been stabbed in one of them, but couldn't see any permanent damage.

S

, indicating multiple breakages. I looked closely at both of his eyes, because I had heard he'd been stabbed in one of them, but couldn't see any permanent damage.

He talked with his hands like gangsters do in movies. It was very hard not to be charmed by his mixture of wit, bonhomie and strident speech.

He wasn't tall, maybe six-foot, but he was clearly strong. He was thick all over. He later told me that was because there's nothing much else to do in prison aside from lift weights.

While Parente looked like he'd wandered off

The Sopranos

lot, Luther appeared as Scottish as his last name indicates (although he later told me he's of Irish descent). He looked bigger than he said he was and had a great deal of natural muscle. He had long, wavy reddish-brown hair and a more thoughtful face than I normally associate with bikers. Aside from the tattoos, he looked more like people I know in the music business than the bikers I've interviewed. He didn't say much â this was clearly Parente's show â but enjoyed a laugh and indicated there was a deep backstory to him.

The Sopranos

lot, Luther appeared as Scottish as his last name indicates (although he later told me he's of Irish descent). He looked bigger than he said he was and had a great deal of natural muscle. He had long, wavy reddish-brown hair and a more thoughtful face than I normally associate with bikers. Aside from the tattoos, he looked more like people I know in the music business than the bikers I've interviewed. He didn't say much â this was clearly Parente's show â but enjoyed a laugh and indicated there was a deep backstory to him.

They were nervous about ordering. I told them not to worry, that an interested TV producer would be paying for dinner. To get the ball rolling, I ordered a pint of Stella Artois, Parente got a Coors Light, Luther, significantly, had a coffee. I ordered bruschetta for the table and a pizza before thinking that it might offend a guy named Mario “The Wop” who'd rather be called Mike.

He ordered a pizza, too. He flirted a little with the young, plain-looking waitress. Luther claimed not to be hungry, but I insisted. He said he'd have a slice. Confused, the waitress said they only serve whole pizzas. He demurred and said he'd share Parente's.

Before we started talking, Parente put his hand on my notebook. Clearly he didn't want me to write anything down. That was fine with me. I have a great memory.

For the next four hours, Parente talked. And he was fascinating. A charismatic guy who really knows how to tell a story, he told me what it's like to be a biker, what it's like to do time and what it's like to shoot someone. He told me things I didn't know about Stadnick and some of the cops, lawyers and bikers I had interviewed. To my surprise, he didn't dodge a single question, and he told me quite frankly how it felt to kill another man.

For a reporter, it was a gold mine. I knew he wasn't going to say anything to incriminate himself or libel anyone else, but I also knew that he'd provide an unprecedented look inside Canadian outlaw biker gangs.

He asked me what I intended to write. I told him that my thesis was that Stadnick's Hells Angels were doing everything they could to build a national empire and that the biggest obstacle to moving into Ontario was Parente and his Outlaws, but that politics and law enforcement and other factors had changed all that. He smiled and said that was actually pretty accurate.

There was a couple at the table next to us. She was about 25 and wearing less than the weather demanded. Parente had already commented on her appearance in frank terms. She was with a neatly dressed, well-coiffed man in his late 50s, maybe 60. It had been obvious that she was listening to our conversation and, now that she'd had a few drinks, she'd finally gathered the courage to talk to us.

Looking right at Parente, she gestured at her date and said as a curly blonde lock fell between her eyes: “You probably don't know this, but he's the best criminal lawyer in Hamilton.”

Without missing a beat, Parente looked him up and down and asked him: “Oh yeah? What's your name?”

The guy, looking and sounding rather pompous, told him.

Parente chuckled. “I've heard of you; but you're not the best.” Then he returned to our conversation.

Chapter 1Death of a Godfather

A man lay in a pool of his own blood on a Hamilton sidewalk struggling for breath. It was May 31, 1997. His death was the start of a revolution that decided who was in charge of organized crime in Ontario.

He wasn't a Hells Angel or an Outlaw. And he certainly wasn't a Loner or Para-Dice Rider or anything like that. He wasn't a biker at all, and neither was the man who killed him.

No, he was John “Johnny Pops” Papalia. He was the Godfather of the Hamilton Mafia, and the primary source of cocaine and other drugs â as well as a mastermind of prostitution, loan-sharking and other products delivered via organized crime â in Southern Ontario.

John “Johnny Pops” Papalia

Born in 1921 to a Calabrian family in Hamilton, Papalia dropped out of school at 13, so he could get into the family business â organized crime. His father, Antonio, was one of a close-knit group of Italians in Hamilton that ran liquor into the U.S. during prohibition (the same men smuggled liquor

into

Canada during its own, earlier era of prohibition). “I grew up in the '30s, and you'd see a guy who couldn't read or write but who had a car and was putting food on the table,” Johnny said proudly. “He was a bootlegger, and you looked up to him.” Antonio was also a prime suspect in the assassination of Rocco Perri, Hamilton's first Godfather.

into

Canada during its own, earlier era of prohibition). “I grew up in the '30s, and you'd see a guy who couldn't read or write but who had a car and was putting food on the table,” Johnny said proudly. “He was a bootlegger, and you looked up to him.” Antonio was also a prime suspect in the assassination of Rocco Perri, Hamilton's first Godfather.

John Papalia developed an even more profound mistrust of authority than you'd expect, even from someone who spent their whole life involved in organized crime. It happened when his beloved father was confined at an internment camp during World War II. His crime was being a prominent Italian. Johnny is said to have taken it hard.

With prohibition long over in both countries and most of the Hamilton Mafia veterans and leaders involuntarily working in Northern Ontario, Johnny did what he could to get by. That generally meant burglaries. He was so successful at it that he started a prosperous fencing operation in an abandoned ice warehouse at the corner of Railway and Mulberry Streets, across the road from where he lived with his mother, Rosie, whose cousins had been involved with Perri's business. Papalia was not a big man â maybe five-foot-eight and slight â but he had a reputation for extreme violence, and was rarely messed with.

He was first arrested in 1945 for a burglary, but he didn't see any real jail time until 1947, when he was caught running an illegal gambling house in his warehouse. Inside, he met a successful Toronto heroin dealer named Harvey Chernick (who, in turn, was being supplied by Sicilian Antonio Sylvestro). In the almost two years they were behind bars together, Chernick taught him the trade and hooked him up with suppliers.

Almost as soon he started selling heroin, Johnny got caught. A cop spotted him making a deal in front of Toronto's busy Union Station and took him in. But Papalia was, above all, resourceful. At his trial, he told the judge that he wasn't selling a drug, but buying one. In the days before sophisticated forensics, he convinced the judge that the white power he had wasn't heroin, but a patent medicine cooked up by a friend. It was the only thing, he said, that helped relieve the pain of his syphilis.

The judge â apparently believing nobody would admit in a public forum to having syphilis unless he really had it â bought the story and gave him two years less a day if he promised to see a doctor when he was released.

Papalia did his time and was rewarded for keeping his mouth shut with an apprenticeship in Montreal with some friends of Sylvestro's â Luigi Greco and Carmine Galante. Both were big-time mobsters, who had met with the likes of Lucky Luciano and had strong ties with the Manhattan-based Bonanno crime family. In fact, Galante had been Joseph Bonanno's personal driver and had been sent to Montreal by him specifically in an attempt to dominate the city's drug trade.

After he had learned the ropes, Papalia went back to Hamilton where he bought a taxi company on the city's heavily Italian James Street North. The cops believed that the cabs were just a front for a gambling ring. When one of the drivers, Tony Coposodi, was executed with two bullets to the back of the head, suspicions that the bootlegger's boy was up to no good increased.

Throughout the '50s, Papalia played the part of the area Godfather with great gusto. He had big, fancy cars, wore expensive suits, squired around lots of pretty women and always carried at least $1,000 in cash with him. He always liked to flash what he called “reds and browns” ($50 and $100 bills) wherever he went.

He had protection-racket money coming in from Montreal and extortion-racket money and gambling-house money coming in from Toronto, in addition to what he made in Hamilton. Although he had many slices of many different pies there, the bulk of his money came from an ingenious loan-sharking scheme. He would lend money to anyone, especially business owners. They would agree to pay back $6 for every $5 borrowed. If it wasn't repaid in a week, every $5 of the new balance would require a $6 repayment the following week. Few could afford this outrageous 1,040 percent annual interest. Traditionally when a debtor defaults to the Mafia, they take what they can from him and then kill or severely injure him. And there's little doubt that Papalia and his men did plenty of that, but he gave some business owners another option. They could just put in his vending machines â he had since set up a company at his old Railway Street headquarters called Monarch Vending Machines â with all the profits going back to him. Of course, the debt wouldn't be forgiven, just some of the interest knocked off. It was incredibly lucrative â because much of what they sold in the vending machines was stolen through truck hijackings or warehouse burglaries â and it even gave him the veneer of a legitimate business.

Papalia made the big time in 1959. He was the only Canadian invited to a meeting in New York that set up what was later to be known as “the French Connection.” Joe Valachi, the minor-league gangster who later turned world-famous informant, was in attendance and testified that he knew of Papalia as a capo (boss) who ran much of Southern Ontario under the auspices of the Buffalo-based Magaddino Family.

The plan was to source high-grade heroin from the Middle East, funnel it through France and then ship it to New York, the distribution point for North America.

Papalia worked extensively with the Sicilian Agueci brothers until 1961, when Vito Agueci was arrested and the Magaddinos had Alberto Agueci murdered. But that didn't slow Papalia down. He found new European connections â including Sicilians working out of France â to keep the heroin supply steady. And he understood that it was just business. There were no hard feelings between him and the Magaddinos over the dismissal of the Aguecis.

Back home, Papalia became a victim of his own ambition. For years he had been involved in an extortion racket with a group of mostly Jewish bar owners, but he decided he wanted it all. One man, Max Bluestein, refused to play ball, so Papalia and his men showed up at his Yonge Street jazz club, the Town Tavern. When Bluestein exited the bar, Papalia and his men beat him nearly to death with a metal pipe. No less a celebrity than Pierre Berton referred to it as a “semi-execution,” and made it the focus of a personal anti-organized crime campaign in his newspaper column.

But not a single one of the literally hundreds of people who witnessed the beating outside the popular nightclub on the country's busiest stretch of pavement came forward to testify against Papalia. Even Bluestein claimed not to know who did it to him.

But a marked increase of police raids on his and his associates' businesses convinced Papalia â or, more likely his boss, Magaddino â that he should turn himself in. He got 18 months.

Other books

Cranioklepty by Colin Dickey

Mosquito Chase by Jaycee Ford

Devil’s Wake by Steven Barnes, Tananarive Due

The 1st Chronicles of Thomas Covenant #2: The Illearth War by Stephen R. Donaldson

Veteran by Gavin Smith

To Mend a Broken Heart by K.A. Hobbs

Seducing Seven (What Happens in Vegas) by MK Meredith

The Yellow House Mystery by Gertrude Warner

When It's Right by Jennifer Ryan

A Wealth of Unsaid Words by R. Cooper