Jia: A Novel of North Korea (3 page)

Read Jia: A Novel of North Korea Online

Authors: Hyejin Kim

don't know when I was born. I don't know whether my

don't know when I was born. I don't know whether my

-mom ever saw my face or just left for the other world

without a glimpse of me. I still wonder whether my father

is alive or dead. After giving birth to me, my mother didn't

get enough to eat-no bowls of miyeokguk, no honey, eggs,

or pork-not even the most basic food for a woman just

out of childbirth. Instead, my grandmother soaked the placenta and umbilical cord in water, drained them of blood

(they shrink and turn white), cut them into tiny cubes,

and coated them with sugar so that my mom could swallow each piece in one bite. She wasn't supposed to chew,

in order to protect her teeth, which were still soft from the

punishment of pregnancy, but she was too weak to swallow. In the end, this sustenance didn't help enough; perhaps

she didn't want to share this world with me.

My grandmother liked to say I was a troublemaker even

in the womb. It seemed I wanted out as soon as possible.

My mom often rolled on the floor, clutching her stomach

after a flurry of my kicks; they were sure I would be a boy,

that I had been a soccer player in my previous life.

My grandmother's face would bloom with a smile when

she said, ` Jia, you don't know how happy we were when

we saw you for the first time. We were so relieved that

you were an adorable girl, and not the tough little nut of a

boy we were expecting. Your sister and I couldn't handle

that, and now I don't have to worry about you going crazy

about soccer and coming home injured, like your father

did when he was a boy."

My father's and mother's photographs were hidden in a

recess of my grandmother's closet. My grandfather didn't allow me to see them, and when he discovered me holding my

parents' pictures in my hands, he scolded me bitterly. He also

shouted at my grandmother; he didn't know she had held on

to them, and that whenever I wasn't feeling well she dandled

me on her knee and showed me the photos for comfort. She

would talk for hours about my father and mother, their love

for each other, and my mother's extraordinary beauty.

In his individual photos, my father never smiled. His

thick hair was brushed straight back from his forehead; his

eyes were two long slits, staring directly into the camera,

as if in challenge. He looked stubborn, with his triangular

face and thin lips. In the photos with my mother, however,

he was transformed: his eyes turned to half-moons as he

smiled; he looked like a bashful boy.

When my father saw my mother for the first time, dancing

in her traditional hatibok with the grace of a pink-winged butterfly, he fell in love instantly. When I saw the pictures, I

envied her big eyes, straight legs, and thin waist. She put on

such bright makeup and wore beautiful dresses, and always

smiled in her pictures. I wondered if she still smiled in the

other world.

My sister also remembered our mother. When my body

was feverish, she would hold my hand in bed and talk

about her.

"At first, I despised you. I believed you took Mom to

the other world. I didn't want to see you or take care of you

at all. You would cry for days at a time-you were always

hungry, because we couldn't feed you well. I even prayed

you would go back to your world and Mom would return

in your place. But Jia, you're my treasure now. I can't stand

it when you're sick-don't be sick anymore." We fell asleep

hugging each other tightly. Her hand was like magic, and

my fevers never lasted very long.

When I was small, I came down with any and every disease

a child could have. Vomiting was a regular part of my life;

fever frequently occupied my body. My grandparents and

my sister worried whenever symptoms of a new disease came

on, because they couldn't get suitable medicine. Sometimes

they had to watch over my ailing body helplessly for several

days, never sleeping. I don't get sick easily anymore. Perhaps

my trials as a child gave me the strength I have now.

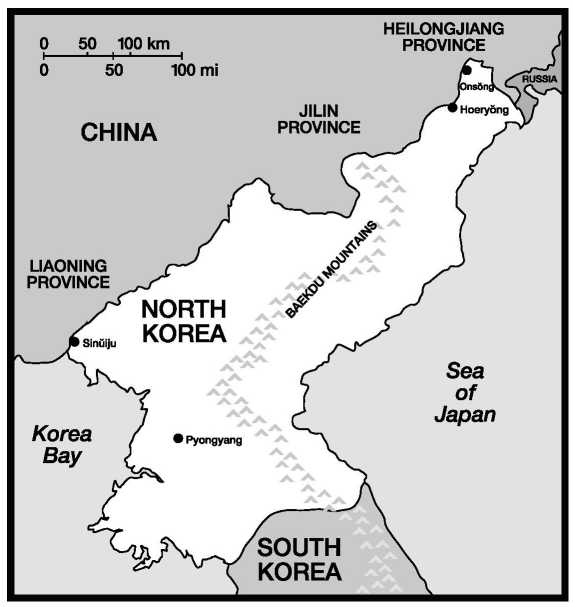

There weren't many people in the part of North Korea

where my family lived. Mountains stretched in all directions, and what few people there were fit into either of two

categories: "extremely bad" and "commonly bad." The extremely bad were locked inside barbed-wire fences, and the

commonly bad lived outside the fence. We were fortunate to be in the second group. The "inside people," as we called

them, had faces stained with coal ash and were perpetually

bent over, their eyes staring at the ground, no matter how

old they were. The men in dark-green uniforms, however,

had clean faces and shiny shoes.

My grandparents strictly forbade my sister and me from

walking along the fence. Sometimes I looked down at the

camp from high up on the hill; I could see the contrasting

faces of the residents and the guards.

We didn't talk with our neighbors much. People seemed

to be too tired to talk to each other. Adults left their house

early and came back with black dust on their faces. My

grandfather and grandmother were not exceptions. My

grandfather had back trouble and often coughed up phlegm.

My grandmother's problems were not as serious, as her job

cooking for the white-faced guards in the camp was less

dangerous than his. I spent many evenings waiting for her

to come home with leftovers, like rice cakes or glutinous

rice jelly. "Today was a lucky day for you girls," she would

say, shuffling through the door with a wrinkled smile.