John Aubrey: My Own Life (27 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

. . .

12 April

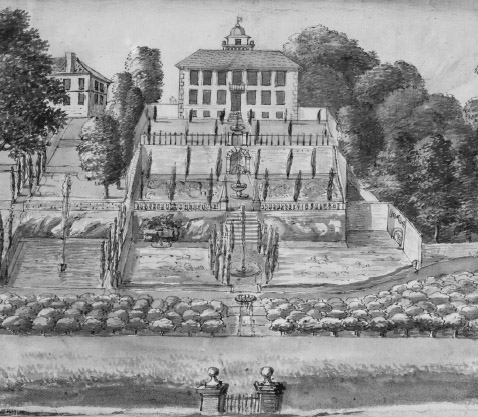

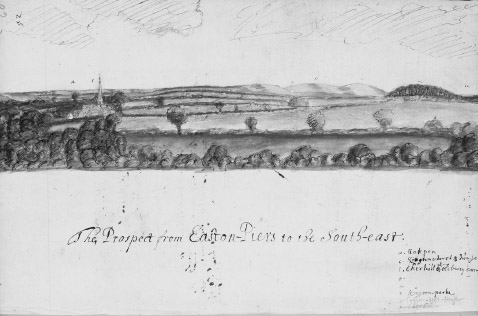

Today I made sketches of the prospects of Easton Pierse: the trees and the thin blue landscape that surround this house I love. The prospect from Easton Pierse is the best between Marsfield and Burford, and though all along that ridge of hills between those two towns are lovely prospects, none has so many breaks and good ground objects as the prospect from Easton Pierse.

Many of the old ways

91

are lost, but some vestigia are left. Anciently there was a way from the gate at the brook below my house to Yatton Keynell, and another by the pound and manor house, leading northwards to Leigh Delamere and southwards to Allington, but there is no sign of it left now.

I remember how my grandfather

92

told me that back at the beginning of the century, the land from Easton Pierse to Yatton Keynell was common land and the inhabitants of Yatton and Easton put cattle on it equally. Likewise, the land between Kington St Michael and Draycot Cerne was common field, where the plough maintained a world of labouring people. In my time, much has been enclosed, and every year more and more is taken in. Enclosures are for the private, not the public good. After it has been enclosed, a lone shepherd and his dog or a milkmaid can manage the land that used to employ several score labourers when it was worked as ploughed land. Ever since the Reformation, when the enclosures began, these parts have swarmed with poor people.

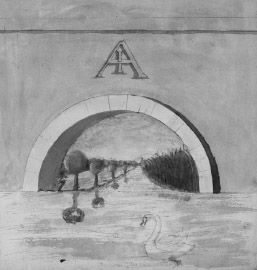

I have sketched my house at Easton Pierse and marked with a cross my grandfather’s chamber where I was born. If it had been my fate to be a wealthy man I would have rebuilt my house in the grandest of styles. I would have added formal gardens in the Italian mode of the kind I have seen at Sir John Danvers’s house in Chelsea and at his house in Lavington. It was Sir John who first taught us in England the way of Italian gardens. I would have erected a fountain like the one that I saw in Mr Bushell’s grotto at Enstone: Neptune standing on a scallop shell, his trident aimed at a rotating duck, perpetually chased by a spaniel. I would have carved my initials on a low curved bridge across the stream. I would have remade my beloved home in the shape of the most beautiful houses and gardens I have visited in my unsettled life, tumbling up and down in the world. But fate has taken me on a different path and the house of my dreams is mere fantasy: a pretty sketch on paper.

I have collected together

93

my drawings of Easton Pierse, my beloved house and its prospects, and designed a grand title page: Designatio de Easton Piers, by the unfortunate John Aubrey! Alas, I fear I will soon be an exile! I am mindful of Ovid’s description of Daedalus, exiled on Crete:

tactusque loci natalis amore

(touched by love for his birthplace). I will make this one of the epigraphs for my book of drawings.

There is smallpox in Taunton again this year.

. . .

May

I saw Mr Wood today

94

in London and told him the news that the Welsh antiquary Percy Enderbie, the author of

Cambria Triumphans

, died recently.

. . .

September

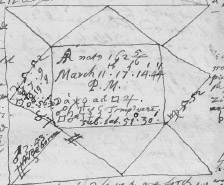

I am at Broad Chalke

95

. I have received the astrological chart of my birth from Mr Thomas Flatman and it reveals no end of trouble. He has made the figure of my nativity and found it agreeing with all the misfortunes of my life. Part of my unhappiness has proceeded from Venus, love, and love affairs, altogether ineffectual so far, together with Saturn in my house of marriage.

. . .

My former servant

96

, Robert, has left a hat and other keepsakes for me with Mr Browning’s maidservant. He has other items to present to me when I can pay him for his services.

. . .

As Ovid tells us, families, and also places, have their fatalities:

Fors sua cuiq’loco est

(Ovid,

Fasti

, Lib. iv).

. . .

This year, not far

97

from Cirencester, there came an apparition, which when asked if it be a good spirit or bad, returned no answer, but disappeared with a curious perfume and most melodious twang. My friend Mr William Lilly believes it was a fairy.

. . .

Mr Lodwick, my friend

98

and Mr Hooke’s, has sent me an essay he has written on the Universal Character, which continues the search for an artificial language he began as a young man when he published

A Common Writing

(1647) aged just twenty-seven. In his new essay Mr Lodwick seeks to describe all possible sounds using a new syllabic notation (vowels are expressed as diacritics). Possible sounds and their notations are presented in a table that allows certain syllables to be placed, even if they are not used in a particular language. In this way, he has invented a way of truly writing what is pronounced, or truly pronouncing what is written. Mr Lodwick claims his system is complete, rational and therefore universal. He hopes it will lead to the construction of a philosophical language.

. . .

November

I think I have now done about three quarters of my perambulation of Wiltshire. In the spring I hope I can do what remains to be done in two or three weeks. I must hope to do it invisibly to avoid arrest for my debts. I feel as though I am working under a divine impulse to complete this task: nobody else will do it, and when it is done no one hereabouts will value it: but I hope the next generation will be less brutish.

I have sought out the Roman, British and Danish camps and the highways. I have traced Offa’s Dyke from Severn to Dee and Wednesdyke and corrected Mr Camden’s

Britannia

in some places, and his claim as to where Boudicca’s last battle was. I surveyed the camps and found out the places of the battles by the barrows. Sir John Hoskyns and Dr Ball say this work is the best I have done: but it is dry meat.

Between south Wales

99

and the French sea, I have taken account of the several kinds of earth and the natural observables in it, and the nature of the plants, cattle and people living off each respective soil.

When I was a boy

100

, my grandfather used to tell me the story of Mr Camden’s visit to the school at Yatton Keynell in the church there. Mr Camden took particular notice of a little painted glass window in the chancel, which has been dammed up with stones ever since I can remember, presumably to spare the parson the cost of glazing it.

Also in Yatton Keynell

101

, on the west side of the road, where it forms a ‘Y’ shape, there is a little close called Stone-edge. From this name, one might expect a stone monument, but if there was ever one there, time has defaced it. There is a great quarry of freestone nearby, which would be suitable for building such a monument. I am inclined to believe that in most counties of England there are, or have been, ruins of Druid temples.

Mr Samuel Butler

102

told me that Mr Camden much studied the Welsh language and kept a Welsh servant to improve him in that language for the better understanding of our antiquities.

. . .

The Roman architecture flourished

103

in Britain while the Roman government lasted, as appears by history, which makes mention of their stately temples, theatres, baths, etc., and Venerable Bede in his History tells us of a magnificent fountain built by the Romans at Carlisle in Scotland, that was remaining in his time. But time and northern incursions have left us only a few fragments of their grandeur. The excellent Roman architecture degenerated into what we call Gothic by the inundation of the Goths.

The Roman architecture came again

104

into England with the Reformation. The first house then of that kind of building was Somerset House. Longleat in Wiltshire was built by Sir John Thynne, steward to the Duke of Somerset. The next house that I can find about London is the new Exchange, then the Banqueting House at Whitehall, by King James. In the time of King Charles I: Greenwich, Queenstreet, Lincoln Inn Fields. By now it has become the most common fashion.

. . .

30 November

Today I presented

105

the Royal Society with an old printed book in the Ancient British language. It will be added to the Society’s library.

. . .

15 December

Today I gave

106

two more books to the Royal Society:

Grammatica Linguae: Cambro-Britanniae

, by Dr Davies; and

Heronis Ctesbii Belopoica: Telefactivia

by Bernardinum Baldum.

I have also presented

107

the Society with a piece of Roman antiquity: a pot that was found in Weekfield, in the parish of Hedington in Wiltshire in 1656. When it was found it was half full of Roman coins (silver and copper) from the time of Constantine. I explained to the learned Fellows that this was the site of a Roman colony and the foundations of many houses and much coin has been found there.

. . .

Anno 1671

January

Since the Great Conflagration of London, many of the inscriptions in the city’s churches are not legible any more, but there is one for Inigo Jones that can still be read notwithstanding the fire. The inscription mentions that he built the banqueting house and portico at St Paul’s. Originally, there was a bust of Inigo Jones too, on top of this monument, but Mr Marshall in Fetter Lane took it away to his house (I must see it).

I am pleased to hear

108

that Mr Payne Fisher has gone round transcribing as many of the London inscriptions that remain legible since the fire as he can find.