John Quincy Adams (14 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

Meanwhile, the French navy warred with Britain on the high seas and provoked the British to attack and seize ships they suspected of trading with their enemyâneutrals as well as belligerents. Apart from preventing arms and ammunition from reaching France, the British intended to halt the flow of foodstuffs and starve the French into submission. With each American ship the British seized, they impressed dozens of English-speaking seamen into the Royal Navy, and without a navy of its own to protect her merchant fleet, the United States could not retaliate.

A month before John Quincy Adams left for Europe, President Washington acted decisively to end the turmoil on American soil. He ordered Major General “Mad” Anthony Wayne to attack Indians in the West, and on August 20, Wayne's legion of 1,000 marksmen crushed the Indian force and sent surviving warriors reeling westward. Buoyed by Wayne's victory, President Washington ordered Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to assemble a fighting force to attack the whiskey rebels outside Pittsburgh. On September 19, with John Quincy two days out to sea, nearly 13,000 troops from four states converged on Carlisle and Bedford, Pennsylvania, and at 10 a.m. on September 30, Washington took field command of the armyâthe first and last American President to do so. Only at the last minute did he cede command when aides warned him he was too important to the nation to risk injury or death in battle.

At Washington's side was Hamilton, who had first served Washington as a twenty-two-year-old captain seventeen years earlier during the

Revolutionary War, which also began as a protest against taxes. Now, as secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton had imposedâand Washington had endorsedâa tax that provoked a similar rebellion, which the two old comrades in arms were determined to crush. The irony was not lost on either man.

Revolutionary War, which also began as a protest against taxes. Now, as secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton had imposedâand Washington had endorsedâa tax that provoked a similar rebellion, which the two old comrades in arms were determined to crush. The irony was not lost on either man.

By early December, an elated vice president wrote to his son, “Our army under Wayne has beaten the Indians and the militia have subdued the insurgents, a miserable though numerous rabble.” Abigail Adams was equally enthusiastic: “The insurgency is suppressed in Pennsylvania . . . [and] General Wayne's victory over the savages has had a happy effect upon our tawny neighbors. . . . The aspect of our country is peace and plenty. The view is delightful and the more so when contrasted with the desolation and carnage which overspread a great proportion of the civilized world.”

5

5

Both parents enthused over their son's career. “Your rising reputation at the bar,” John Adams wrote to his son, “your admired writings upon occasional subjects of great importance, and your political influence among the younger gentlemen of Boston sometimes make me regret your promotion and the loss of your society to me.” He signed it, “With a tender affection as well as great esteem, I am, my dear son, your affectionate father John Adams.” Abigail ended her letter with the hope that “you will not omit any opportunity of writing to her whose happiness is so intimately blended with your prosperity and who at all times is your ever affectionate Mother Abigail Adams.”

6

6

Although John Quincy's ship developed leaks “like a water spout,” he and his brother landed safely in Dover on October 14, less than a month after leaving Massachusetts. As their coach from shipside reached London Bridge, however, “we heard a rattling . . . a sound as of a trunk falling from the carriage. My brother immediately alighted and found the trunk of dispatches under the carriage. . . . Our driver assured us that the trunks could not have fallen unless the straps had been cut away.” The incident left John Quincy shaken:

Entrusted with dispatches of the highest importance . . . to negotiations between the two countries, with papers particularly committed to my care

because

they were highly confidential by the President of the United States . . . with what face could I have presented myself to the minister for whom they were intended? . . . The story would be resounded from one end of the United States to the other.

7

because

they were highly confidential by the President of the United States . . . with what face could I have presented myself to the minister for whom they were intended? . . . The story would be resounded from one end of the United States to the other.

7

Â

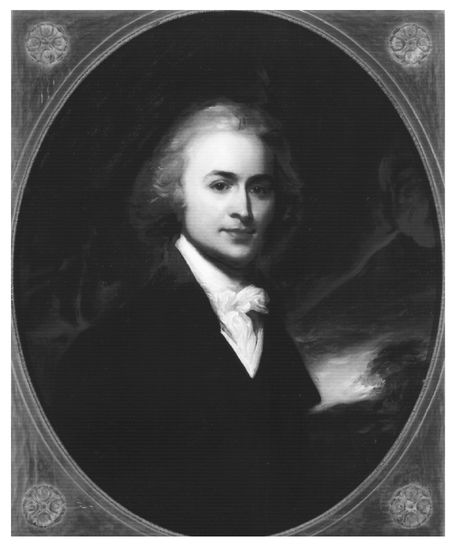

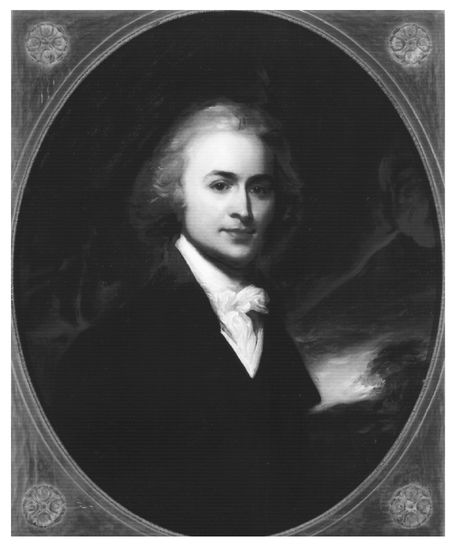

John Quincy Adams, at twenty-nine, sailed to Europe to assume the post his father had once held as American minister to Holland.

(AFTER A PORTRAIT BY JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

(AFTER A PORTRAIT BY JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

His memoirs go on interminably, as he relived the incident and postulated how “the straps were cut by an invisible hand.”

8

Adams was immensely relieved to deliver the trunk to John Jay's quarters the next morning, along

with papers for Thomas Pinckney, the American minister plenipotentiary in Britain.

8

Adams was immensely relieved to deliver the trunk to John Jay's quarters the next morning, along

with papers for Thomas Pinckney, the American minister plenipotentiary in Britain.

Far from being in “a situation of small trust and confidence,” as he had feared when he accepted his assignment in Holland, John Quincy Adams spent the next three days helping to determine the fate of his nation with Chief Justice John Jay and U.S. ambassador to England Thomas Pinckney, former governor of South Carolina. Together they put the finishing touches on a treaty that would set the course of Anglo-American relationsâand, indeed, much of the Western worldâfor the foreseeable future.

Jay had arrived in London four months earlier, on June 6, and obtained the British government's agreement to exclude noncontraband goods from the ban on American trade with France and the French West Indies. He had also won three other major concessions: withdrawal of British troops behind the Canadian border from the Northwest Territory, limited resumption of American trade with the British East and West Indies, and establishment of a most-favored-nation relationship between the two nations, with preferential tariffs for each. Both sides agreed to set up a joint commission and accept binding arbitration to settle British and American financial claims against each other. The treaty made no mention of two issues that had long provoked American anger toward Britain: impressment of American sailors into the British navy and failure to compensate southern planters for thousands of slaves the British had carried away during the Revolutionary War. The slave issue lay behind the fanatical southern support for France and the willingnessâindeed, eagernessâof southerners to join France in war against Britain.

Although Jay had hoped to win concessions on both issues, he recognized that Britain had little incentive to yield on either. Aside from her economic and military power, Britain had scored an important naval victory over the French fleet that left British warships in full command of the Atlantic Ocean, with no need to cede privileges to weaker nations.

“As a treaty of commerce,” John Quincy concluded, “we shall never obtain anything more favorable. . . . It is much below the standard which I think would be advantageous to the country, but with some alterations

which are marked down . . . it is preferable to a war. The commerce with their West India Islands . . . will be of great importance.”

9

which are marked down . . . it is preferable to a war. The commerce with their West India Islands . . . will be of great importance.”

9

John Quincy left with his brother for Holland on October 29, arriving in The Hague two days later and settling into their official quarters. He had effectively established himself as American minister by January 19, 1795, when General Charles Pichegru, commander of the French Army of the North, marched into the Dutch capital with a contingent of 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers. Their arrival caused so little disruption that John Quincy's brother Thomas went to theater the following evening with the American consul general, Sylvanus Bourne. A day later, John Quincy went with Thomas and Bourne to the French authorities, who told them “they received the visit of the

citoyen ministre

of a free people, the friend of the

peuple français

with much pleasure. That they considered it

tout à fait une visite fraternelle

.”

l

citoyen ministre

of a free people, the friend of the

peuple français

with much pleasure. That they considered it

tout à fait une visite fraternelle

.”

l

The substance of the business was that I demanded safety and protection to all American persons and property in this country, and they told me . . . that all property would be respected, as well as persons and opinions. . . . They spoke of the President, whom, like all Europeans, they called General Washington . . . that he was a great man and they had veneration for his character.

10

10

General Pichegru had served with French forces in the American Revolution and was true to his word, doing nothing to interfere with John Quincy's activities or those of other Americans in Holland. Despite the presence of French troops, The Hague proved to be exactly what Secretary of State Edmund Randolph and President Washington had anticipatedâa listening post in the heart of Europe, and for John Quincy Adams, it proved the perfect first post in the diplomatic service. His academic training combined with his knowledge of languages and an extraordinary memory to accumulate names, descriptions, and thinking of dozens of

diplomats from everywhere in Europe, along with invaluable military and political intelligence from warring parties and other sectors of the continent. “Dined with the French generals Pichegru, Elbel, Sauviac,” the pages of his journal disclose, “and a Colonel . . .

diplomats from everywhere in Europe, along with invaluable military and political intelligence from warring parties and other sectors of the continent. “Dined with the French generals Pichegru, Elbel, Sauviac,” the pages of his journal disclose, “and a Colonel . . .

“ . . . the Dutch general Constant and a colonel Comte d'Autremont . . .

“ . . . the minister of Poland Midleton . . .

“ . . . the Prussian secretary Baron Bielefeld . . .

“ . . . the Russian minister . . .

“The French made use of balloons during the last campaign in discovering the positions of their adverse armies . . . Pichegru and the other generals assured us on the strongest terms that it was of no service at all. . . . âOh! yes,' said Sauviac, âthe effect was infallible in the gazettes.'”

11

11

John Quincy spent as many as six hours a day writing reports, which included twenty-seven letters to the secretary of state from November 1794 to August 1795 and ten long, explicit letters to his father, the vice president. He emerged as one of Europe's most skilled diplomats and America's finest intelligence gleaner. He prophesied that while Britain and France wore each other down in war, America would grow and prosper. “At the present moment, if our neutrality is preserved,” he predicted, “ten more years will place the United States among the most powerful and opulent nations on earth.”

12

12

John Quincy's reports elated his father. “Never was a father more satisfied or gratified,” Vice President John Adams wrote to John Quincy in the spring of 1795, “than I have been with the kind attention of my sons.”

Since they went abroad, I have no language to express to you the pleasure I have received from the satisfaction you have given the President and secretary of state, as well as from the clear, comprehensive, and masterly accounts in your letters to me of the public affairs of nations in Europe, whose situation and politics it most concerns us to know. Go on, my son, and by a diligent exertion of your genius and abilities, continue to deserve well of your father but especially of your country.

13

13

In addition to visits, dinners, and other social events with diplomats and French officers, John Quincy continued his studies, reading histories of every European state while adding Spanish to the three other languages he was able to read and speak. “The voice of all Europe,” he discovered, had hailed President George Washington's Neutrality Proclamation. Although it had not attracted much attention initially, it quickly established a new principle of international law as well as American constitutional law. Although rules abounded governing relations between warring nations, the world had ignored the rights of neutrals until George Washington raised the issue.

“The nations that have been grappling together with the purpose of mutual destruction,” John Quincy wrote, “are feeble, exhausted, and almost starving. Those that have had the wisdom to maintain neutrality have reasons more than ever to applaud their policy, and some of them may thank the United States for the example from which it was pursued.”

14

14

As the end of his first year in the diplomatic service approached, John Quincy was quite content with his new career. Although he called Holland “insignificant” in comparison to diplomatic posts in Paris and London, he told his father that it was “adequate to my talents . . . without being tedious or painful . . . and leaves me leisure to pursue a course of studies that may be recommended by its amusement or utility. Indeed, Sir, it is a situation in itself much preferable to that of . . . a lawyer's office for business which . . . is scarcely sufficient to give bread and procures more curses than thanks.”

15

15

To his surprise, John Quincy's next set of State Department orders emanated from a new secretary of stateâTimothy Pickering of Massachusetts, whom Washington had named to replace John Randolph. Randolph had resigned following charges he had accepted bribes from the French government. For John Quincy Adams, the appointment was not unpleasant. Born in Salem, Pickering was a Harvard graduate and lawyer, a staunch Federalist who had served with distinction in the Revolutionary War and as postmaster general before becoming secretary of war early in 1795.

Other books

The Taint: Octavia by Taylor, Georgina Anne

The Case of the Peculiar Pink Fan by Springer, Nancy

Just Peachy by Jean Ure

On The Prowl by Cynthia Eden

Night Games by Richard Laymon

Midnight for Charlie Bone (Children Of The Red King, Book 1) by Jenny Nimmo

Emma's Blaze (Fires of Cricket Bend Book 2) by Piper, Marie

Visioness by Lincoln Law

The Image by Jean de Berg