John Saturnall's Feast (41 page)

Read John Saturnall's Feast Online

Authors: Lawrence Norfolk

‘No.’

‘Then what will you do?’

Her head was thrown back, her black eyes watching him. He leaned forward until he felt her breath on his stinging cheek. Her free hand gripped his arm, to push him back or draw him closer he did not know. But he saw her lips part. Then he closed her mouth with his own. They hung there, joined by lips and fingers. As he reached to clasp her tighter, she twisted away. But it was to take his hand and draw him down the gallery. He followed her to the door at the end.

Inside the chamber they stared at each other, their breathing quick and shallow. A moment later her hands were pulling at his clothes. His own fumbled at her laces. For a few seconds they swayed, locked together. Then they tumbled down onto the bed.

’'And on these far-flung Shores such amorous Sweets may be fashioned too . . .”

From

The Book of John Saturnall:

A

Feast

for

Old Saint Andrew's Day,

being a

Bagatelle

and a Cinglet of

Sugar

for

One Beloved

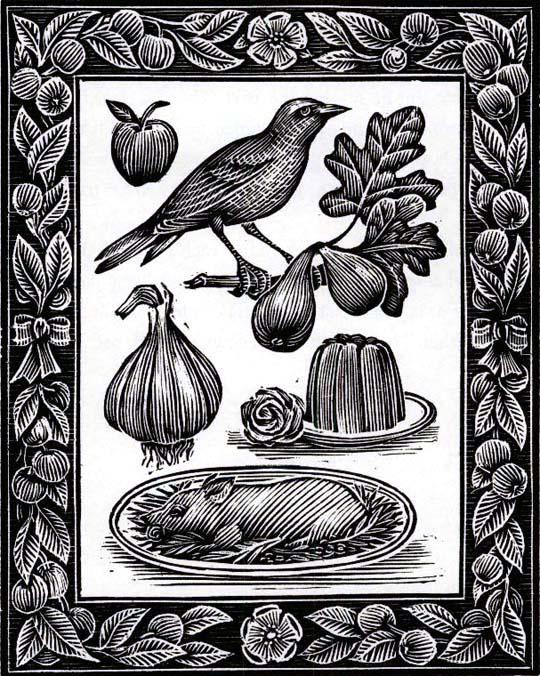

or the Love of Adam did Eve pluck an Apple and make of it a Dish. Solomon fed Sherbets and Rose Jellies to the Maids that warmed his Bed. Even now do we token our Affections with Dishes and Feasts. No Snow fell in Eden, I believe. And Foxes, not Hedge-priests, did afflict the Garden of Solomon. Yet even in the Depths of Winter a Cook may serve his Mistress a Gift to match those Pleasures that Lovers afford one Another.

or the Love of Adam did Eve pluck an Apple and make of it a Dish. Solomon fed Sherbets and Rose Jellies to the Maids that warmed his Bed. Even now do we token our Affections with Dishes and Feasts. No Snow fell in Eden, I believe. And Foxes, not Hedge-priests, did afflict the Garden of Solomon. Yet even in the Depths of Winter a Cook may serve his Mistress a Gift to match those Pleasures that Lovers afford one Another.

The Spanish in their Privacy, I have heard, do offer one another the Loin of a Piglet which has never yet stood, that tenderest Fillet being seared in Oil, rolled in Seasoning and diced. The French dangle above each other's dainty Maws those Birds we call Fig-peckers, roasted and dusted in Sugar, and oftentimes with the Feathers unplucked. The Amants of the Duchy of Bavaria eat sweet Pork Dumplings and those of Prussia crunch tiny Biscuits called Widewuta's Teats after their first Empress. The Romans eat much Garlic and the Hungarians more while in the Markets of Sidon lovelorn Men pay Ransoms for a Jelly dusted with Sugar from which the Scent of Roses does rise and which no veiled Maid can taste without yielding.

And on these far-flung Shores such amorous Sweets may be fashioned too, and given, and consumed even in the depths of Winter, as I shall now relate . . .

T

HE SNOW FELL FASTER

, the heavy flakes cartwheeling down out of the sky, swirling and whirling in the gusts of wind, piling up in drifts. With the roads cut, Buckland Manor rose like a great dark ship riding at anchor in a sea of white. Within its walls, its crew hurried and scurried to prepare themselves for the voyage through winter.

Tramping into the woods, John led the Kitchen into the orchard-men's abandoned gardens from where they carried down baskets of skirrets and carrots, fat leeks and leathery green kale, pink-topped mangels and purple-bottomed turnips. From the clamps came baskets of tiny apples.

‘Ha!’ exclaimed Mister Bunce. ‘Remember these, Master John?’

They scoured the woods for fallen timber and drove down the pigs and ewes from Home Farm. The pigs were housed in the stables while the sheep were penned in the sagging barracks whose roof groaned under the weight of the snow. There, amid squeals and bleats, Mrs Gardiner tutored Ginny, Meg and the maids in the art of milking. The farm's chickens joined Diggory Wing's doves.

John cleared Scovell's room and Mrs Gardiner sent down bedding for the cot. Every night, once the kitchen's work was done, John made his way back through the passages, rushlight in hand, towards the Master Cook's chamber.

But at the junction he turned away from Scovell's room. Taking the door at the far end and hurrying through the deserted kitchen, he climbed the narrow staircase to the Solar Gallery where the moon offered a ghostly light, scudding over the snow-bound lawns to shine through the high casements. When the moon sank the gallery was dark. But from under the door at the far end, a crack of light showed, glowing from the bedchamber. There Lucretia waited.

The first night she had trembled beneath him, her dark eyes staring up. He found himself frozen by her gaze, fearing to injure her or brush against her grazed knees. But at last Lucretia had pulled him to her and it seemed that a tight string within her was cut. Her arms and legs splayed. He heard her breathing grow hoarse and felt her arch to receive him. At last they fell back. John felt for her hand. ‘I had not thought such pleasure might be mine,’ Lucretia said.

‘Nor I,’ he said beside her. ‘Yet it is.’

Their pleasures were repeated the next night, and the one after that. John recalled the woman in the barn. How his nerves had paralysed him at first. Now his tongue felt dry in his mouth and his heart thudded in his chest. But his desire for Lucretia increased.

She was not bold, she told him. She made him turn his back while she tugged at laces and stays or pulled off her shift then slipped unseen beneath the covers. But once they touched, she abandoned her reserve. She pulled him to her and ran her hands down the smooth slopes of his back. He buried his face in her hair or pressed his lips to hers. Soon she kicked off the covers, spreading her arms that he might have the pleasure of looking upon her.

He laid fires in the hearth and watched her stand before the flames, raising an eyebrow at his gaze or touching a finger to her lips as if to preserve the silence. She brought her book and held its torn and taped pages to the flickering light, the coverlet draped around her shoulders.

Come live with me, and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove,

That valleys, groves, hills and fields,

Woods, or steepy mountain yields

. . .

A belt of straw and ivy buds,

With coral clasps and amber studs:

And if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me and be my love.

John let the words dress her, imagining the cap of flowers, the mantle embroidered with leaves, the gown of lambswool and the belt with its amber studs. Lucretia closed the book and smiled.

‘Gemma and I used to pretend a shepherd would come and carry us off.’

‘Instead you got a cook.’

‘I am content with my cook.’

‘And what of the valleys and groves?’

‘Here is where I want to be,’ she said. ‘Here in this room.’

They pushed off the heavy blankets, revealing themselves to each other in the fire's flickering light. His gaze played over the curve of her back, down her thighs and slender legs. Her fingers combed his thick black hair, finding the scar left on his scalp by the musket ball.

She brought a candle and held it over his body.

‘You are very dark, Master Saturnall.’

‘I'm told my father was a blackamoor.’

‘And was he?’ She passed the candle back and forth, her face so close he could feel her breath on his skin.

‘Or a Barbary pirate.’

‘And your mother?’

He regarded her across the pillow. ‘You set eyes on her once. But I do not think you will recall.’

He told her how his mother had come to the Manor and how she had left. The mysterious argument between Almery and Scovell. ‘Mrs Gardiner called him a magpie. He tried to steal from her.’

‘Steal what?’ she asked.

‘A book. Or so I believe. Did you not wonder how a kitchen boy came to read?’ He described the lessons his mother had taught on the slopes then his life in the village with Cassie and the others. He told her how the sickness gripped the village. Then their flight and the ruined palace in the woods. The anger that had burned inside him and how the sight of Clough had ignited it again. At last he spoke of Saturnus and the woman who had brought the Feast.

‘She was called Bellicca,’ John said. ‘She came here when the Romans went home. She brought the Feast to the Vale. Every green thing grew in her garden, my ma said. Every creature that walked or crawled or flew or swam. The Feast was for all, she said. Back then, all men and women sat together as equals and exchanged their affections . . .’

‘As we do,’ Lucretia said. She smiled but John had not finished.

‘Then Coldcloak came,’ he told her, his expression darkening. ‘Some say he loved her. Others that she was a witch who enchanted him. He sat at her table and took his place at the Feast. But he had sworn an oath to Jehovah's priests. Bellicca had witched the whole Vale with her Feast, they claimed. So Coldcloak vowed to take it back for Christ. He pulled up her gardens. He doused the fires in her hearths and chopped up her tables. He drove her people out and took every green thing. The Feast was lost, except for the book . . .’

He stopped. Lucretia's smile had faded and a strange look had taken its place. Suddenly she seemed remote from him.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘Only that he betrayed her,’ she said quickly. ‘That he sat at her table then turned on her.’ She shook her head as if to rid herself of the thought then gripped his arm. ‘Promise you will never betray me.’

Before the gazes of the servants they were cool, addressing each other with a stiff formality. But Philip had to remind John of dishes he had set simmering or those left to cool. Ephraim Clough had made off with his head, he told John in exasperation.

Motte's men shovelled out the stones from the chapel and moved in a table. They gathered there on Sundays to sing a psalm and join in prayer. As Christmas approached, John and Philip scoured the larders and storehouses.

‘We've as many apples as we could wish,’ Philip reported. ‘Bacon, hams, half a sack of dried fruits, some jars of conserves, that sugarloaf in the larder. Two sacks of meal. The ewes are still giving milk. Mrs Gardiner has said she will make slip-cheese and whey. The carrots and turnips in the clamps are good. We can make frumenty, and a minced-meat cake. We can slaughter a pig. But we need more wood. The pile in the yard is almost gone . . . Are you listening, John?’

He celebrated the long nights with Lucretia, kept safe by the heavy dark curtains. She read the verses from her book to him, sitting by the fire then stepping carefully around the chair, the little table and cradle for fear of disturbing the dust. She dressed her hair in plaits so that he might have the pleasure of releasing the coils, winding the thick locks around his fingers then letting them fall over her face. Her dark eyes watched from behind the disorderly fringe.

‘The first moment I saw you,’ she murmured, ‘I hated you.’

He nodded drowsily. ‘I hated you too.’

They gazed at each other across the long bolster.

‘What if they knew?’ John said quietly. ‘Piers. Sir William . . .’

‘They are far away.’

‘But when they return?’

‘Then you will leave me,’ Lucretia said. ‘You will ride away down the Vale. You will forget me . . .’

‘I will not,’ John said. ‘You will marry Piers.’

‘Perhaps he will find another. One more to his taste. The women of Paris are most alluring, I hear. What is your opinion, Master Saturnall, on the women of Paris?’