John Saturnall's Feast (9 page)

Read John Saturnall's Feast Online

Authors: Lawrence Norfolk

A dark form loomed above. An instant later the man knelt beside her. She had thought she would expire of shame when he had stripped off her brown wool dress. She was a loosemouth, he had admonished her, to speak so promiscuously with the son of Susan Sandall. But she would have endured a thousand such penances.∼ She was God's messenger, he had told her. Now the man's blue eyes found her own.

‘Are you prepared, Sister Cassandra?’

A disturbance of the gloom, John thought first. His mother's worsening cough had driven him out. He stood in the meadow, the water jug clutched in his hands. High above something was moving on the slope. As he watched, a tattered white pennant seemed to flutter out of the dark brambles. Someone was descending. He stood before the door of the hut. Only when the figure reached the lowest terrace did John recognise the bonnet.

Cassie advanced through the long grass. But as she drew near he saw her halting gait. Her limbs moved with awkward jerks. Abruptly she stumbled and fell. John dropped the jug and ran forward, offering his hand to the girl. But then he recoiled.

There seemed no part of Cassie that had not been scratched. Long red lines ran over her limbs. Her woollen dress hung in tatters. Blood smeared her hands and forearms. She had used them, it seemed, to protect her face.

‘Cassie?’

‘I know the witch.’

Her blue eyes were almost black in the gloom.

‘Come with me,’ he told her. ‘My ma will help you.’

But she shook her head, rising stiffly to her feet. ‘I saw her go up there.’ Cassie looked up the slope to the dark line of trees.

‘But there's no way in,’ John replied. ‘It's all thorns, remember?’

‘That don't make no difference.’ The girl stood before him in her shredded dress. ‘I told you, John. Witches don't bleed.’

A sinking feeling grew in John's stomach. He heard the hand-bell ring out from the green below. Faint shouts answered the clanging noise.

‘God sent you to help me,’ Cassie said, stumbling through the grass. ‘You led me to her, John.’

‘Cassie, wait,’ he pleaded. But at the top of the bank the girl launched herself forward. Together they half ran, half fell down the bank. Picking himself up beside the trough, John heard a familiar voice.

‘Took your time, John.’

Ephraim Clough stepped out of the hedge. John straightened and faced the older boy. Ephraim glanced at Cassie.

‘What have you done to her, Witch-boy?’ He turned towards Two-acre Field, and shouted, ‘I've found her! Over here!’

A sick feeling gathered in John's stomach, familiar and unwanted. But against it rose a new anger. He stared at the boy's heavy brow, his full cheeks and broad face. With a cry, John sprang, his first punch rapping the top of Ephraim's skull, stinging his knuckles and drawing nothing more than a surprised grunt from his opponent. But the second swing ended in a gristly crack as his fist found Ephraim's nose. Ephraim gave a cry and clutched his face. A giddy abandon took hold of John. He wrestled his enemy down then he and Ephraim were rolling about the path, grabbing and punching and kicking. Ephraim was bigger and stronger but John's anger seemed to lend him a new strength. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Cassie stumble away. He heard the hand-bell ringing. He hit out again and again, careless of the blows that Ephraim returned. At last he pinned his opponent, trapping the boy's arms. Blood streamed from Ephraim's nose.

‘Go on, Witch-boy,’ he dared John. ‘We'll see how your ma sings.’

The words only enraged John more. He raised his arm. He would punch the boy's face as hard as he could. Keep punching until he was silent. But even as he shaped to deliver the first blow a hand gripped his shoulder. He was pulled backwards. A furious face glared into his own.

‘Where have you been!’ his mother hissed. ‘Come, John! Hurry!’

They were running again, running as hard as they could, the long grass whipping their legs, across the dark meadow and towards the first bank. Once again, oily tallow-smoke laced the night air and the banging of pots and pans mixed with the villagers’ shouts. Once again John heard his mother's breath rasp in her throat. Arms flailing, they hauled themselves up the first slope, the heavy bag bumping between them. Then the next and the next in a furious scramble. Only when the ghostly banks of furze and scrub rose around them did they look back.

Flickering lights ringed their hut with fire. The villagers were gathered all around. Then, as John and his mother watched, the first torch was thrown, tumbling end over end, drawing an arc of flame through the darkness to land on the roof of their hut. The pale yellow flames flickered, licking the thatch then spreading over the roof.

A tongue of red fire rose into the night. Around the hut the villagers were a dark mass, surging back and forth. He did not need to see their torchlit faces. Not only Marpot and his Lessoners but all the villagers were there: the Fentons and Chaffinges and Dares and Candlings, all the rear-pew women who had knocked on their door and their children too. As if Ephraim's thick-browed face were stamped on the faces of Seth and Dando and Tobit. Only Abel had stood by him, dying of fever in his bed. The fire took hold and it seemed to John that the flames ran through his own veins, their heat spreading through his frame. He had been right, he thought. He and Ephraim both. They did not belong here. They had never belonged.

He looked up at his mother. Her hands were pressed to her mouth, her eyes wide. Below, the hut blazed, the smell of smoke strong in the air. John reached up and took her hand.

‘Ma?’

But she could only shake her head.

They resumed their climb. Soon the banks of brambles stretched out thick arms. The bag bumped between them as John and his mother edged their way into the thickets. When they reached the final bristling barricade, his mother wrapped her arms about him. A moment later she had plunged them both into the thorns.

The spines would tear his skin as they had Cassie's, thought John. He flinched as the first canes scraped his legs . . . But the stems and leaves rustled harmlessly. His mother seemed to part the brambles as easily as Moses did the sea. Emerging on the other side, he found himself unmarked. As he wondered at the miracle, his mother gripped a stem and ran her hand down its length, shucking the spines like peas from a pod.

‘Fool's thorn,’ she said.

John nodded and looked up. At the top of the bank, sheathed in deep-lined bark, the ancient trunks of Buccla's Wood leaned like pillars supporting a massive canopy. John scraped together a heap of dry leaves and lay down with his mother. Far below their hut smouldered, a red eye glaring out of the darkness. Deep inside him, John felt his anger glow like a hot coal.

A magpie cackled. Sunlight glittered. John opened his eyes and blinked in the glare. For one blissful moment, he wondered how he came to be lying on a bed of leaves at the edge of Buccla's Wood. Then his memory blew the hot ember into life: the shouts and cries, the flames, the familiar faces turned to a chanting mass. He felt the red coal lodge itself deeper inside him.

Beside him, his mother slept, her long black hair spread out over the ground. As John rose, she stirred. He looked down the slope to the roofless shell at the edge of the meadow. Smoke still rose from the blackened walls. His mother placed a hand on his shoulder.

‘You said we belonged there,’ he told her. ‘You said we belonged more than any of them.’

‘We do,’ she answered.

But she paid no attention to the hut nor even the village. He followed her gaze down the Vale, leaping hedgerows and woods, tracking the river until it disappeared. There was the ridge and the gatehouse, the tower of the chapel and the great house beyond. Buckland Manor. That was it, he realised.

‘You served there,’ he said.

His mother rubbed her red eyes. ‘Yes, John. I served there.’

‘But you came back.’

‘I had no choice.’

Another riddle, he thought. Even now.

‘You said you'd teach me,’ he said.

‘I will,’ she answered shortly. ‘Come.’

She heaved the bag onto her shoulder and turned to the woods behind her. But as John turned to follow a flash of light caught his eye.

It came from the distant house. A second flash followed. Then more. A row of windows was being opened, John realised. Sunlight was glinting off the panes. He stood on the slope and watched the lights flash like signals sent the length of the Vale. Then he turned and followed his mother into Buccla's Wood.

“

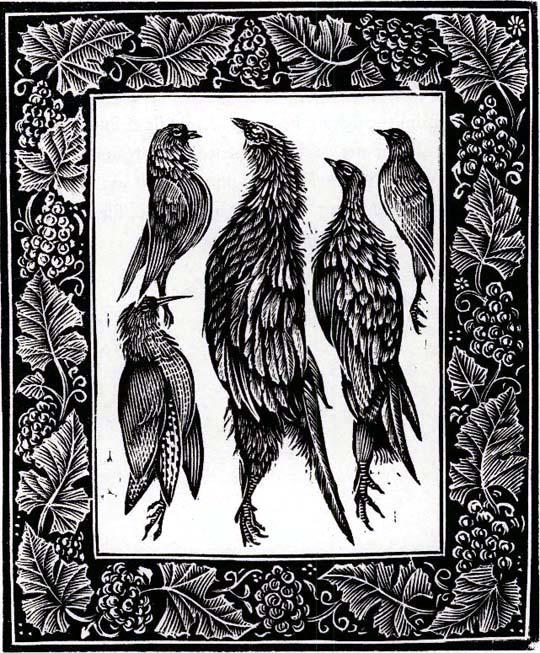

Take

your birds and carve them each according to its Fashion.

”

From

The Book of John Saturnall

: For a

Dish

called a

Foam

of

Forcemeats

of

Fowls

true Feast has Mysteries for Parts, some clear to discern and others running deeper. Its Dishes speak in Tongues to baffle a Scholar yet a humble Cook must decipher them all. So the Air, being a Garden as Saturnus taught, a Cook must rename its Tree-tops as Beds and its Planters are Nests where Birds and Fowls fatten themselves and thrive in wondrous Variety. And to celebrate that Garden's Harvest he must exert his Art as I will tell you here.

true Feast has Mysteries for Parts, some clear to discern and others running deeper. Its Dishes speak in Tongues to baffle a Scholar yet a humble Cook must decipher them all. So the Air, being a Garden as Saturnus taught, a Cook must rename its Tree-tops as Beds and its Planters are Nests where Birds and Fowls fatten themselves and thrive in wondrous Variety. And to celebrate that Garden's Harvest he must exert his Art as I will tell you here.

Take your Birds and carve them each according to its Fashion. Unbrace the Mallard, rear the Goose, lift the Swan, dismember the Hern, unjoint the Bittern, display the Crane, allay the Pheasant, wing the Partridge, thigh one each of Pigeon and Woodcock and leave a Pair of Fig-peekers whole. Pluck them and draw them then roast them till the Skins are golden. Excepting the Fig-peekers, pick the cooled Meats in Strings no thicker than Packthread, chop them fine and season alternately with Cumin and Saffron. Take Whites of Eggs and beat them to the Airiness of Clouds. Fold each of the Meats in part of the Egg.

Fit a Pipkin close with a Cake-cage and steam it. Place the Pastes within, one inside the next divided by stiff Paper rubbed with clear Butter, the greater Birds outermost and the smaller within. At the Centre set the Fig-peekers. Let the Steam cook these Forcemeats and all the Time watch them, removing the Papers Layer by Layer. When all are risen and set, loosen the Cake-cage and lift out the set Foam of Forcemeats. Cut to show the Layers within, coloured red and yellow. Serve in Slices upon Sippets or fine Plates, as you please.

T

HE PROTOCOLS

WERE SIMPLE

, Lady Lucretia reminded herself. She had, after all, rehearsed them so many times.

In the presence chamber, noble ladies might approach Her Majesty. But they might not speak unless invited. In the privy chamber beyond, Her Majesty's Privy Ladies were permitted a salutation — but woe betide the courtier who presumed to direct remarks. Beyond that lay the withdrawing chamber where different rules applied. For there Her Majesty's most-beloved ladies might speak without her express leave, a privilege held by right, Lady Lucretia reminded herself, only by the wives and mistresses of visiting kings. The withdrawing chamber should be lively with whispers and shared confidences. Abuzz with snippets of gossip and advice. But that was not the innermost sanctum. Last of all, at the far end of the humming capsule, stood the door to the bedchamber proper.