Johnny Tremain (10 page)

Authors: Esther Hoskins Forbes

Seemingly neither the moon nor the stars above him nor the dead about him cared.

Then he lay face down, sobbing and saying over and over that God had turned away from him. But his frenzied weeping had given him some release. He must have slept.

He sat up suddenly wide awake. The moon had seemingly come close and closer to him. He could see the coats of arms, the winged death's heads, on the slate stones about him. He was so wide awake he felt someone must have called his name. His ears were straining to hear the next words. What was it his mother had said so long ago? If there was nothing left and God Himself had turned away his face, then, and only then, Johnny was to go to Mr. Lyte. In his ears rang his mother's sweet remembered accents. Surely for one second, between sleeping and waking, he had seen her dear face, loving, gentle, intelligent, floating toward him through the moonlight on Copp's Hill.

He sat a long time with his arms hugging his knees. Now he knew what to do. This very day he would go to Merchant Lyte. When at last he lay down, he slept heavily, without a dream and without a worry.

I

T WAS PAST DAWN

when he woke, his feeling of contentment still in him. He was no longer his own problem but Merchant Lyte's. Tomorrow at this time what would he be calling him? 'Uncle Jonathan?' 'Cousin Lyte?' Perhaps 'Grandpa,' and he laughed out loud.

Only imagine how Mrs. Lapham would come running, dropping nervous curtsies, when he drove up in that ruby coach! How Madge and Dorcas would stare! First thing he did would be to take Cilla for a drive. He'd not even invite Isannah. But how she would bawl when left behind! And then ... his imagination jumped ahead.

At the Charlestown ferry slip he washed in the cold sea water, and because the sun was warm sunned himself as he did what he could to make his shabby clothes presentable. He combed his lank, fair hair with his fingers, cleaned his nails with his teeth. Of course now he could buy Cilla that pony and cart. And Grandpa Lapham ... oh, he'd buy him a Bible with print an inch high in it. Mrs. Lapham? Not a thing, madam, not one thing.

Christ's Church said ten o'clock. He got up and started for Long Wharf where his great relative had his counting house. On his way he passed down Salt Lane. There was the comical little painted man observing Boston through his tiny spyglass. Johnny wanted to stopâtell that fellowâthat Rabâof his great connections, but decided to wait until he was sure of his welcome into the Lyte family. Although half of him was leaping ahead imagining great things for himself, the other half was wary. It was quite possible he would get no welcome at allâand he knew it.

He walked half the length of Long Wharf until he saw carved over a door the familiar rising eye. The door was open, but he knocked. None of the three clerks sitting on their high stools with their backs to him, scratching in ledgers, looked up, so he stepped inside. Now that he had to speak, he found there was a barrier across his throat, something that he would have to struggle to get his voice over. He was more excited than he had realized. But he was scornful too. These three clerks would not even look up when he came in today, but tomorrow what would it be? 'Good morning, little master; I'll tell your uncleâcousinâgrandfather that you are here, sir.'

Finally a well-fed, rosy youth, keeping one finger in his ledger, swung around and asked him what he wanted.

'It is a personal matter between myself and Mr. Lyte.'

'Well,' said the young man pleasantly, 'even if it is personal, you'd better tell me what it is.'

'It is a family matter. I cannot, in honor, tell anyone except Mr. Lyte.'

'Hum...'

One of the elderly clerks laughed in a mean way. 'Just another poor suitor for the hand of Miss Lavinia.'

The young clerk flushed. Johnny had seen enough of Madge and Dorcas and their suitors to know that the gibe about poor boys aspiring to Miss Lavinia had gone home.

'Tell him,' snickered the other ancient spider of a clerk, 'that Mr. Lyte isâahâsensible of the great honorâahâand regrets to say he has formed other plans for his daughter's future. Ah!' Evidently he mimicked Mr. Lyte.

The young clerk was scarlet. He flung down his pen. 'Can't you ever forget that?' he protested. 'Here, kid,' and turned to Johnny. 'Mr. Lyte's closeted behind that door with two of his sea captains. When they leave, you just walk in.'

Johnny sat modestly on a stool, his arrogant shabby hat in his good hand, and looked about him. The three backs were bent once more over the ledgers. The quill pens scratched. He heard the gritting of sand as they blotted their pages. There was a handsome half-model of a ship on the wall. Sea chests, doubtless full of charts, maps, invoices, were under the desks.

The door opened. Two ruddy men with swaying walks stepped out and Mr. Lyte himself was shaking hands, bidding them success on their voyaging, and God's mercy. As he turned to go back to his sanctuary, Johnny followed him.

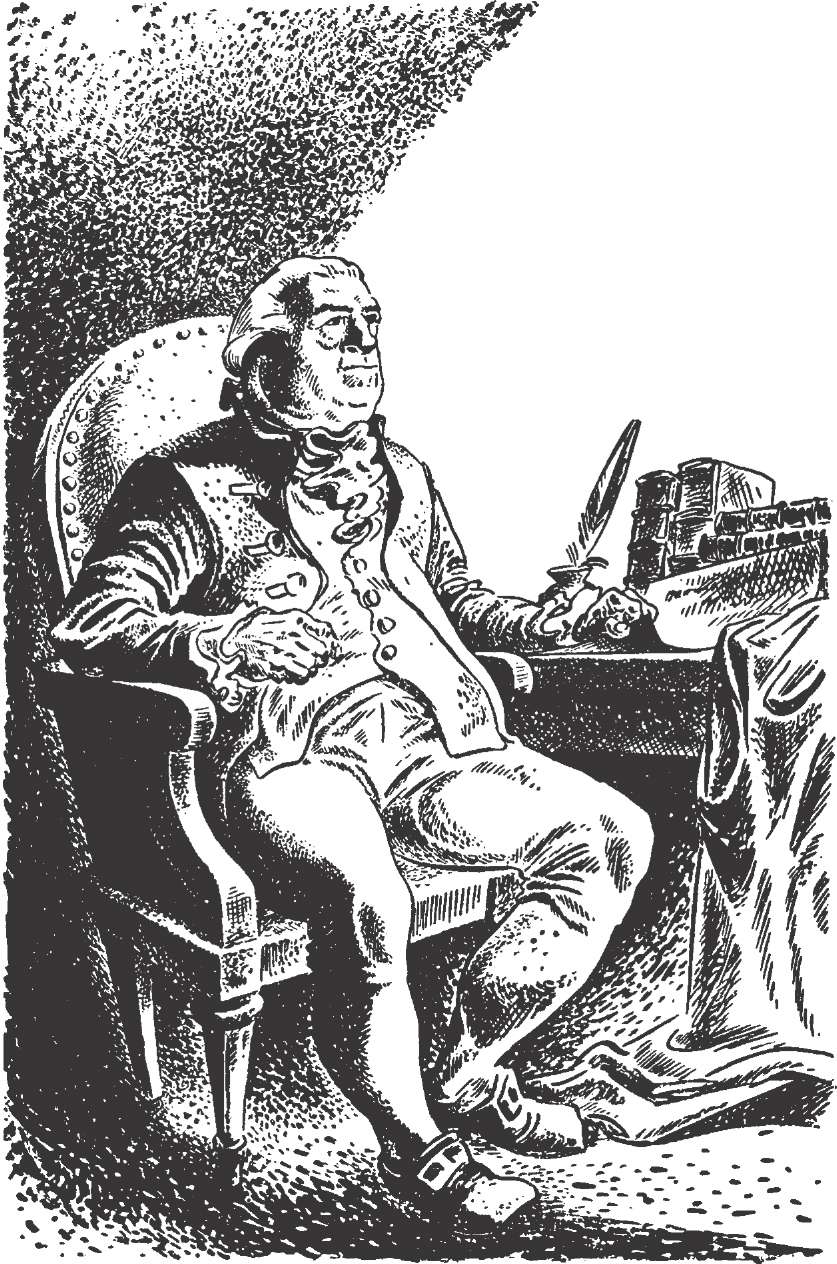

Mr. Lyte sat himself in a red-leather armchair beside an open window. Through that window he could watch his

Western Star

graving in the graving dock. He would have been a handsome man, with his fine dark eyes, bushy black brows, contrasting smartly with the white tie-wig he wore, except for the color and quality of his flesh. It was as yellow as tallow. Seemingly it had melted and run down. The lids were heavy over the remarkable eyes. The melted flesh made pouches beneath them. It hung down along his jawbone, under his jutting chin.

'What is it?' he demanded. 'Who let you in? What do you want, and who, for Heaven's sake, are you?'

'Sir,' said Johnny, 'I'm Jonathan Lyte Tremain.'

There was a long pause. The merchant's glittering black eyes did not waver, nor the tallow cheeks redden. If the name meant anything to him, he did not show it.

'Well?'

'My mother, sir.' The boy's voice shook slightly. 'She told me ... she always said...'

Mr. Lyte opened his jeweled snuffbox, took snuff, sneezed and blew his nose.

'I can go on from there, boy. Your mother on her deathbed told you you were related to the rich Boston merchant?'

Johnny was sure now Mr. Lyte knew of the relationship. 'Yes, sir, she did, but I didn't know you'd know.'

Know?

I didn't need to

know.

It is a very old storyâa very old trick, and will you be goneâor shall I have you flung out?'

'I'll stay,' Johnny said stubbornly.

'Sewall.' The merchant did not raise his voice, but instantly the young clerk was on his threshold. 'Show him out, Sewall, and happens he lands in the water, youâah! can baptize him with my nameâah ... ha, ha!'

Mr. Lyte took up a handful of papers. The incident was over.

Sewall looked at Johnny and Johnny at Sewall. The young man was as kind as his cherubic face suggested.

'I can prove to you one thing, Mr. Lyte. My name is Jonathan Lyte Tremain.'

'What of it? Any back-alley drabtail can name her child for the greatest men in the colony. There should be a law against it, but there is none.'

Johnny's temper began to go.

'You flatter yourself. What have you ever done except be rich? Why, I doubt even a monkey mother would name a monkey child after you.'

Mr. Lyte gave a long whistle. 'That was quite a mouthful. Sewall!'

'Yes, sir.'

'You just take this monkey child of a monkey mother out, and drown it.'

'Yes, sir.'

Sewall put a soft hand on the boy's shoulder, but Johnny fiercely shook himself free.

'I don't want your money,' he said, more proudly than accurately. 'Now that I've met you face to face, I don't much fancy you as kin.'

'Your manners, my boy, are a credit to your mother.'

'But facts are facts, and I've a cup with your arms on it to prove what I say is true.'

The merchant's unhealthy, brilliant eyes quivered and glittered.

'You've got a cup of mine?'

'No, of

mine.

'So ... so you've got a cup. Will you describe it?'

Johnny described it as only a silversmith could.

'Why, Mr. Lyte, that must be...' Sewall began, but Mr. Lyte hushed him. Evidently not only Mr. Lyte, but his clerks had heard of this cup. Johnny was elated.

'My boy,' said the merchant, 'you haveâahâbrought me great news. I must see your cup.'

'Any time you say, sir.'

'My long-lost cup returned to me by my long-lost littleâha-haâwhatever you areâkerchoo!' He had taken more snuff. 'Bring your cup to me tonight. You know my Beacon Hill house.'

'Yes, sir.'

'And we'll kill the fatted calfâyou long-lost whatever-you-are. Come an hour after candles are lit. Prodigal Son, what? Got a cup, has he?'

Although Johnny might have been more cordially received by Merchant Lyte, he was satisfied enough with his welcome to build up air castles. He really knew they were air castles, for at bottom he was hard-headed, not easily taken in even by his own exuberant imagination. Still, as he trudged up Fish Street, turned in at the Laphams' door, in his mind he was in that ruby coach. Money, and a watch in his pocket.

He had hoped to slip to the attic and fetch away his cup without being noticed, but Mrs. Lapham saw him enter and called him into the kitchen. She said nothing about his shoes. Evidently the girls had told her his story and she had believed it.

'Johnny, you come set a moment. No, girls, you needn't leave. I want you to hear what I'm going to say.'

Johnny looked a little smug. Had he not (almost) arrived in the Lyte coach?

'Grandpa says as long as he lives you are to have a place to sleep. But you've got to go back to the attic. Mr. Tweedie's to have the birth and death room, and you can have a little somewhat to eat. I've agreed that's all right. I'll manage

somehow

.'

'Don't fret ... I'm going for good.'

'I'll believe that when I see it. Now, mind. I've two things to say to you.'

The four girls were all sitting about, hands folded as though they were at meeting.

'First. You shan't insult Mr. Tweedieâleast, not until he has signed the contract. No more talk of his being a spinster aunt dressed up in men's clothes. And

NO MORE SQUEAK-PIGS.

He's sensitive. You hurt his feelings horribly. He almost took ship then and there back to Baltimore.'

'I'm sorry.'

'Secondly. There's to be no more talk of you and Cilla. Don't you ever

dare

to lift your eyes to one of my girls again.'

Lift

my eyes? I can't see that far down into the dirt even to know they are there.'

'Now, you saucebox, you hold that tongue of yours. You're not to go hanging 'round Cillaâgiving her presentsâand dear knows how you got the money. I've told her to keep shy of you. Now I'm telling you. You mark my words...'

'Ma'am, I wouldn't marry that sniveling, goggle-eyed frog of a girl even though you gave her to me on a golden platter. Fact is, I don't like girlsânor'âwith a black look at his mistressâ'women eitherâand that goes for Mr. Tweedie too.'

He left to go upstairs for his cup.

When he came down, the more capable women of the household were out in the yard hanging up the wash. Cilla was paring apples in that deft, absent-minded way she did such things. Isannah was eating the parings. She'd be sick before nightfall.

Cilla lifted her pointed, translucent little face. Her hazel eyes, under their veil of long lashes, had a greenish flash to them. There never was a less goggle-eyed girl.

'Johnny's mad,' she said sweetly.

'His ears are red! He's mad!' Isannah chanted.

These words sounded wonderful to him. He was happy because once more they were insulting him. They were not pitying him or being afraid of him because he had had an accident.

'Goggle-eyed, sniveling frogs!'

With his silver cup in its flannel bag, he set off to kill time until he might take it to Mr. Lyte.

He spent a couple of hours dreaming of his rosy future. And the tears in Merchant Lyte's unhealthy, brilliant black eyesâthe tremor in his pompous 'ah-ha-ha' manner of speech as he clutched his 'long-lost whatever-you-are' to his costly waistcoat. Even if he did not like women, Miss Lavinia, he decided, was to kiss him on the brow. Through this dreaming he felt enough confidence in his good fortune at last to stop in to see 'that Rab.' There had not been a day since the first meeting that he had not wanted to.