Joseph E. Persico

Authors: Roosevelt's Secret War: FDR,World War II Espionage

Tags: #Nonfiction

Contents

Chapter II. Spies, Saboteurs, and Traitors

Chapter III. Strange Bedfellows

Chapter IV. Spymaster in the Oval Office

Chapter V. The Defeatist and the Defiant

Chapter VI. “There Is No U.S. Secret Intelligence Service”

Chapter VII. Spies Versus Ciphers

Chapter VIII. Donovan Enters the Game

Chapter IX. “Our Objective Is to Get America into the War”

Chapter X. Catastrophe or Conspiracy

Chapter XI. Secrets of the Map Room

Chapter XII. Intramural Spy Wars

Chapter XIII. Premier Secret of the War

Chapter XV. “We Are Striking Back”

Chapter XVI. An Exchange: An Invasion for a Bomb

Chapter XVII. Leakage from the Top

Chapter XVIII. Distrusting Allies

Chapter XIX. Deceivers and the Deceived

Chapter XX. The White House Is Penetrated

Chapter XXI. If Overlord Fails

Chapter XXII. Cracks in the Reich

Chapter XXIII. A Secret Unshared

Chapter XXIV. “Take a Look at the OSS”

Chapter XXV. Sympathizers and Spies

Chapter XXVII. Who Knewâand When?

Chapter XXVIII. “Stalin Has Been Deceiving Me All Along”

To the next generation,

Amanda, Joshua, and Georgia,

and my literary agent,

Clyde Taylor

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

Sun-tzu

The Art of War

Acknowledgments

WRITERS of history and of historical figures must stand on the shoulders of numerous others in order to tell their story. This book could not have been written without the unstinting cooperation of the staff of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York. At the time I began, the library's director was Verne W. Newton, who, in addition to steering me initially in wise directions, read my final manuscript with great care and to the author's profit. I especially benefited from the assistance of the library's supervisory archivist, Raymond Teichman, and Lynn Bassanese was unfailingly helpful and imaginative in handling my queries. Others who aided me at Hyde Park were Robert Parks, Nancy Snedeker, Alycia Vivona, and Mark Renovitch, who was especially helpful in finding photographs. Verne Newton's successor, Cynthia Koch, continued to provide the backing of her staff.

At the National Archives I relied on William Cunliffe, Larry Macdonald, John Taylor, and Sidney Shapiro. At the Library of Congress, I was assisted by Margaret Krewson, former chief of the European Division, Mark Matucci, and Marvin Kranz. I thank Meredith Butler, director of libraries at my alma mater, the State University of New York at Albany, and among her staff I am deeply indebted to William Young for tracking down my endless queries. I have been well served by a talented reference team at the Guilderland, New York Library who researched numerous matters for me. That staff, under the library's director, Carole Hamblin, included Margaret Garrett, Gillian Leonard, Maria Preller, Eileen Williams, Joseph Nash, and Thomas Barnes. At the New York State Library, I was assisted by Jean Hargrave and Eileen Clark.

I received valuable help from the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, beginning with the library's director, Larry Hackman, and particularly from Randy Sowell. The Truman scholar Robert Ferrell was extremely generous to me. Duane A. Watson of Wilderstein Preservation Incorporated opened for me the files of FDR's confidant Margaret Suckley. I was measurably helped by two noted historians of intelligence, Michael Warner of the Central Intelligence Agency and Robert L. Benson of the National Security Agency. Five other accomplished writers in the intelligence field, Thomas Troy, David Kahn, Hyden Peake, Arnold Kramish, and Rick Russell, also provided me with invaluable help. Nicholas B. Sheetz, manuscripts librarian at Georgetown University, generously opened his collection to me. Several of my requests dealing with military matters were filled by the staff of retired General Colin Powell, including his chief aides, William Smullen, Peggy Cifrino, and Larry Wilkerson. Derek Blackburn provided useful Churchill material.

I benefited enormously from the time and freedom provided by fellowships to the Rockefeller Institute Study Center at Bellagio, Italy, and the Bogliasco Foundation, also in Italy. My daughter, Vanya Perez, ably prepared the manuscript. And I thank Edwin Sours, Henry Jurenka, John Foley, and Michael Mattioli, each of whom knows what he did to keep this project moving.

Others who read the manuscript and provided invaluable guidance included my wife, Sylvia LaVista Persico, and fellow writers Bernard Conners and Tanya Melich. I further want to recognize the valued role of my late agent, Clyde Taylor, in the publication of this and my other works. Finally, I was the fortunate author guided by the sure hand of Robert Loomis, my editor, who supplied enthusiasm, judgment, and encouragement throughout this project.

A Note to Readers

THERE exists, for intelligence practitioners and scholars, precise distinctions between codes and ciphers, cryptology and cryptanalysis, coding and encryption, decoding and decryption. However, in the interest of reducing confusion for the general reader, these terms are used here in their broader colloquial sense. Were purist rules to be followed, the Hugh Whitemore play about Alan Turing's role in Ultra would have to be entitled

Breaking the Ciphers,

not

Breaking the Code.

This is a linguistic straitjacket that I have hoped to avoid.

As a Harvard student, FDR developed a code to mask his diary entries, particularly those about his relations with a young Boston lady. (FDR Library)

FDR as assistant secretary of the Navy. His favorite component of the Navy Department was the Office of Naval Intelligence, which he expanded and staffed with trusted socialite friends. (FDR Library)

FDR with his friend Vincent Astor (left), who carried out espionage from his oceangoing yacht and who fed the President intelligence before World War II through The Club, a secret society of highly placed Americans. (FDR Library)

John Franklin Carter, a Washington columnist who ran a spy ring for FDR directly from the Oval Office. (Sonia C. Greenbaum)

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and FDR along a stream at the President's retreat, Shangri-la. Their partnership began with secret correspondence predating America's entry into the war. (FDR Library)

General Claire Chennault (center), the American aviation advisor to China, who became involved in FDR's scheme to firebomb Tokyoâbefore Pearl Harbor. The plan fell through but led to Chennault's formation of the legendary Flying Tigers. (FDR Library)

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was the result of the greatest intelligence failure in American or perhaps all military history. Responsibility for the incident is still hotly debated. (FDR Library)

FDR with Vice President Henry Wallace, who unwittingly provided Germany with some of its highest-level intelligence through leaks to his brother-in-law, a Swiss diplomat. (FDR Library)

William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a World War I Medal of Honor winner, served with the famous Fighting Irish, the 69th Infantry Regiment. He became America's first spy chief when FDR appointed him director of the Office of Strategic Services. (National Archives)

Passport photo of Sir William S. Stephenson, the head of British intelligence in the United States, who fed FDR fabricated evidence of alleged hostile Nazi intentions in the Americas in order to draw the United States into the war. (Thomas Troy)

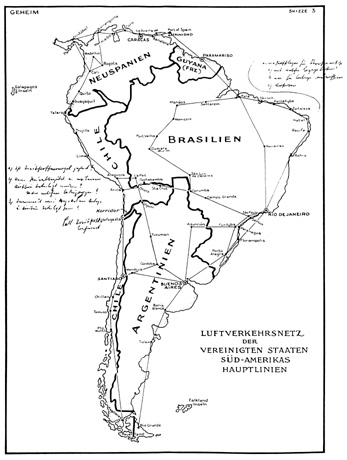

The map of South America that British intelligence sent to FDR supposedly revealed how Hitler proposed to divide the continent into five Nazi duchies. (FDR Library)