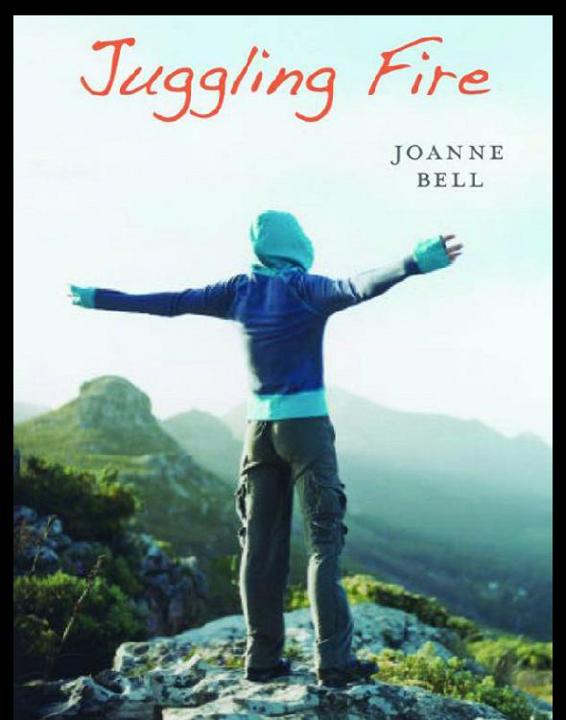

Juggling Fire

Juggling Fire

JOANNE BELL

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

Text copyright ©

2009

Joanne Bell

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bell, Joanne, 1956-

Juggling fire / written by Joanne Bell.

ISBN 978-1-55469-094-7

I. Title.

PS8603.E52J85 2009 jC813'.6 C2009-903348-8

First published in the United States,

2009

Library of Congress Control Number

:

2009929362

Summary

: Sixteen-year-old Rachel embarks on a solo quest to find her father,

who disappeared years ago in the Yukon wilderness.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas, from

The Poems of

Dylan Thomas

, copyright © 1952 by Dylan Thomas. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Design by Teresa Bubela

Cover artwork by Getty Images

Author photo by Mikin Bilina

O

RCA

B

OOK

P

UBLISHERS

PO B

OX

5626,

STN.

B

V

ICTORIA

, BC C

ANADA

V8R 6S4

O

RCA

B

OOK

P

UBLISHERS

PO B

OX

468

C

USTER,

WA USA

98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

Printed and bound in Canada.

Printed on 100% PCW recycled paper.

12 11 10 09 • 4 3 2 1

For Mary with thanks

DO NOT GO GENTLE INTO THAT GOOD NIGHT

(stanzas four through six)

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight,

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears,

I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

—Dylan Thomas

Contents

CHAPTER 6 Building on Permafrost

CHAPTER 12 Pirates in the Night

CHAPTER 13 The Grayling Corral

CHAPTER 15 Clues Undercurrents

PART 1

INTO THAT GOOD NIGHT

Mom doesn’t cry when I heave the packs from the pickup; she only blinks hard, squeezes my shoulders and whirls around, like she has to get away from me fast. If IH1idn’t know her so well, I’d say she was furious. Her face is too tight to figure out.

My older sister Becky, however, hugs me until my backbone cracks.

I gasp.

“THAT doesn’t hurt, Rachel,” she scoffs.

Before I can squeeze out enough breath to yell, she sticks a bag of caramels and a roll of duct tape in my pack’s side pocket. “Got any haywire for Mom’s muffler?”

I shake my head, mentally rolling my eyes. Really! As if I won’t need it more than they will. If I had haywire, I’d hang on to it

.

Mom doesn’t cry when I heave the packs from the pickup;

“Come back alive,” she suggests cheerfully. She removes the caramels, bites open the bag, extracts a palmful for the ride back to town and sticks the remaining candies back in my shirt pocket. “Might be a long, slow drive,” she remarks, rolling her eyes toward Mom. “We’ll need a bite of trail food ourselves.”

Mom’s head is resting on the steering wheel.

“Mom?”

She lifts her head and nods with a small smile. “I love you,” she mouths through the window.

Then she starts the engine.

“Me too,” says Becky. “Got to go.”

She bangs the passenger door shut, rattling the whole truck.

Mom grinds the gears and leans on the horn. Brooks, who is a nervous but sweet dog, crouches, shaking, behind my legs. Lots of things make him shake. Our red pickup bumps and backfires down the gravel mountain road away from me, belching black smoke. The smell of burning brakes drifts over the Yukon tundra, and it sounds like the muffler’s falling off. Mom never did pay much attention to anything mechanical. She’s an artist. The details of everyday life don’t interest her much.

I stare until the truck is out of sight, swallowed by scarlet dwarf-birch leaves and yellow willows. Neither Mom nor Becky leans out to wave at me. To be fair, Mom doesn’t want to start begging me to stay. This trip of mine is her worst nightmare come true.

Brooks, still cowering behind me, and I are finally on our own.

I’ve wanted to do this since I was a little kid. I’m sixteen now, so I’ve waited for almost ten years.

“Come on, boy,” I mutter, balancing the two sides of his pack bags in my hands to be sure they’re even. “Time to stand up.”

Eyeing his load, Brooks slinks to the ground and sweeps his tail hopefully at me. “Not a chance, buddy.” Brooks makes a sound in his throat like a siren warming up, staring at the ribbon of gravel where scattered puffs of exhaust are still floating away. He hates to see anyone in our family leave. Brooks’s idea of a good time is to sprawl by the woodstove with the three of us in sight.

“Up.” I haul him to his feet and buckle the straps under his belly. Breathing in a faint smell of sun and warm dog fur, I snap the final strap around his chest. Brooks at once sinks back down and tucks his head out of sight under his paws.

My stomach clenches. Why am I doing this? I’m not sure I want to anymore.

My pack’s too heavy to lift. I crouch down to slip the straps under my arms and, using Brooks’s skull as a lever, push myself to my feet. Sucking in my stomach, I cinch the belt tight around my hips and buckle up.

No way. I’ll never make it a mile with this load. Panic gusts through me.

I stick my hands under the shoulder straps and lean forward until my breathing slows and deepens. “One step at a time,” I tell Brooks, coaxing him to his feet.

He promptly collapses.

Breathe slowly, I tell myself. I gaze around me. Sunlight lights up a boulder on the slope to my left. For a moment I’m sure it’s a grizzly.

Fear flames from the pit of my stomach up my chest and into my throat. My eyes skitter over the tundra. I feel like a flushed calf streaking to safety. I can be prey here, just like a yearling caribou I saw once, picked over by wolves. Only my jawbone and maybe a hunk of boot will be left.

“Enough,” I say out loud. “Lightning kills more people than grizzly bears do. So does panic. Let’s go, boy.”

Brooks is bunched in such a tight ball that I can’t find his head. I manage to haul him up again by heaving on his pack straps without taking off my own load.

Leading him away from the road, I start down the trail before he has a chance to dig in his paws. Brooks tramps reluctantly at my side, occasionally bumping against my legs, staring pitifully up into my face and whining to make sure I know he’s not into this.

Because we’re on top of a mountain pass, the tundra is spread out for many miles around us. I can see down the sweep of mountains to where we’ll be walking tomorrow. No real trees grow here; the largest shrubs are waist-high clumps of willow and dwarf birch. Out of habit, I trail my fingers along a birch stem. Sandpaper-rough birch twigs scratch my bare legs like thorns.

I could just go home.

A wedge of cranes creaks through the sky; they sound like a chorus of screen doors slamming shut.

It wouldn’t help. I’d still need to do this.

Brooks is half bloodhound and half malamute/Newfoundland cross. His father is Chili, Becky’s wheel dog, the last and usually the strongest dog in the team. Chili’s mother is Becky’s old lead dog, Ginger, and Chili’s father was Dad’s lead dog, Bear, who died one spring day not far from here.

Brooks’s mother is a purebred bloodhound who got loose and came sniffing into Becky’s dog yard, hunting for a mate. Becky and I had just been returning from a walk with Chili. We looked at each other and laughed, and without a word, she unsnapped Chili’s leash. The bloodhound’s owner was relieved to have a good home for a pup. It’s hard to imagine my life without Brooks.

Brooks has a sled dog’s powerful chest and legs, a long thin nose shaped like an icicle, and glacier blue eyes, but weirdly enough, he also has the sagging eyelids, pouches of hanging skin and droopy ears of a hound. Brooks, even when cheerfully chasing rabbits, looks so sad that I hug him every chance I get. He can howl like a husky and bay like a hunting dog. When I hug Brooks, he goes limp, squeezes his eyes closed and sighs with pleasure. Brooks is about as mean and tough as a spring snowball melting into mush.

My hands are moving along Brooks’s head. He nudges me with his nose, hoping for a change of heart. When I keep walking, he dredges up a series of deep mournful bays.

I ignore him. The pack bulges from both his sides, hanging from the ridge of his backbone. He waddles and bumps, but at least he’s staying close.

She has to be nuts. What kind of mother would let me go?

“I’ll give you a month,” Mom said.

“Give me?”

She gouged a minute speck of wood from the caribou she

was shaping. “If I flew in a month after you got there, you

might be ready for company.” She held the carving in front

of her face with both hands and gently blew at the shavings.

I watched them float a moment in a shaft of sunlight before

they slowly sank to the floor.

That’s what she’s usually like. Mom’s always had a pretty

clear sense of when I need to do something, which battles are

hers to fight and which are mine. But she also respects me.

That’s obvious. And because she does, I agreed.

I let her show me what to pack. She suggested lots of

high-calorie foods: butter, chocolate, cheese and nuts. I agreed

to it all.

I hardly eat anything anyway. I don’t need to eat much.

It’s probably bragging to say this, but I’m thin and supple—kind

of like a green willow, Becky says. I’m not anorexic or anything.

I just don’t get hungry too often, which is weird because I’m

extremely tall and, unfortunately, still growing. When I stand

beside Mom or Becky, I find myself hunching over so I don’t feel

so awkward. All my life I was little, and then last year I grew five

inches in nine months. I don’t like it much; I feel like I grew out

of myself.

Sometimes I forget to eat all day. Then at night, I can’t. It’s

weird actually. I look at food and know it will taste good, but

somehow I can’t put it in my mouth. Or I just put in a taste and

then my throat clenches shut.

Mom said when I was little I had chubby cheeks and

I wanted to be a gymnast. She said I was smart and kind

of—jolly. These days I have no idea what I’m going to be.

I mean, I juggle and I memorize fairy tales. How can I make

a life from that? I really do memorize them—page by page.

And when I’ve got them memorized, then I change them.

As Brooks and I bump along, I start to recite a story from an old Irish fairy-tale book Mom read to us when I was small. The original was called “The Princess in the Glass Tower.” My version, which is evolving every time I tell it, is called “When the Princess Bolted from the Palace.”

In the original story a beautiful princess is on display in a glass castle on top of a glass hill. Her father, the king, has decreed that to win her hand and the kingdom, a prince must ride to the top of the hill. This has proven rather difficult, as the king has also decreed that unsuccessful suitors will be either put to death or locked in chains in the dungeon. Unless, of course, they can out-gallop his pursuing knights.

I haven’t looked at the original story for many years. It’s gone through so many versions, first Mom’s and then mine. How do I know what the original story said? Whenever I read a fairy tale that I love—modern or traditional— it reminds me of that first collection of Irish tales. It had black-and-white illustrations and big letters and old-fashioned language. Not just the choice of words was archaic, but the way the sentences were put together. The other thing I remember is that the characters were fearless and stubborn in the face of danger. If they were scared, they stood straighter and whistled in the wind.