Kaboom (13 page)

Authors: Matthew Gallagher

The sheik covered his heart with his long fingers. “I hope no one is hurt,” he said.

I thought about the meeting Captain Whiteback had been forced to attend and the circumstances leading up to it; Lieutenant Colonel Larry and

Sergeant Major Curly believed the line commanders and first sergeants weren't listening to their demands for strict adherence to the published uniform standard. “Me too,” I replied. “How are you, though?”

Sergeant Major Curly believed the line commanders and first sergeants weren't listening to their demands for strict adherence to the published uniform standard. “Me too,” I replied. “How are you, though?”

He sighed heavily and stroked his recently trimmed grey beard. “I am very tired,” he said. “I have been awakened in the night many times due to Mahdi Army attacking my checkpoints.”

“I know. We've been sent out three times in the past week to help.”

He nodded. “Yes, thank you, thank you, from the bottom of my heart. Coalition force support is very important to us, and it gives my men strength. But it is not just no sleep that makes me tired.”

I arched an eyebrow Phoenix's way, thinking something hadn't been communicated correctly, which caused the sheik to continue talking.

“You will see it is harder to sleep when you get old,” he said. “You are still young. Your mind stays with you with the years that come.”

Phoenix's translation wasn't the greatest, but it got the point across. The sheik had explained a concept I already understood and was slowly beginning to experience more and more: The weightier the decisions of the day, the longer they lingered in the night. Enough of my soldiers had accused me of being an insomniac that I had started to believe them.

We continued to talk, three very different men of very different cultural backgrounds and motivations and experiences, stuck in this moment of time like a bug caught in a spiderweb. This particular web stuck with bureaucratic inanity and slowness: What the sheik's people needed and craved, we couldn't provide or wouldn't, in the name of legitimizing the Iraqi government; what I needed and craved, he couldn't provide or wouldn't, due to the potential future of his nation and his neighborhood, his family and himself. We both knew America's time and interest in Iraq was fleeting.

Some forty-five minutes later, after a second round of chai, I realized that I was yawning and we were no longer talking about security or electricity or medical clinics but about Clint Eastwood movies. I thanked Sheik Banana-Hands for his hospitality and began to stand up, but he leaned over and squeezed my shoulder, speaking in his native tongue.

“He say that he has gift for you, LT,” Phoenix said.

Sheik Banana-Hands yelled something in Arabic at his Sahwa bodyguard and clapped, which caused the bodyguard to bounce up from his chair like a jack-in-the-box and disappear into a side room. Phoenix whispered into my ear. “He say something about tube of mortar.”

Fifteen seconds later, the younger Iraqi walked back in, holding a Russian military mortar tube and tripod. Both were immaculately clean. The sheik spoke again.

“He say that his men find this in neighborhood behind house, position facing to the market,” Phoenix translated.

I tried not to sigh audibly. It was all a part of the counterinsurgency game. Like we didn't know they all had their own personal caches leftover from the sectarian wars. Whatever, I thought. It was one more weapon off the street.

I thanked him, cupping my right hand over my heart. “It pleases me that you and your men care so deeply for your people,” I said. “Security brings peace, and peace is what we all seek.”

Sheik Banana-Hands also placed his right hand over his heart. “Peace is wonderful,” he said. “Both in here”âhe tapped at his chestâ“and around us.”

I stared at the wall behind the sheik and fought through the arriving space-out. Phoenix nodded in agreement, moved by the profundity of Banana-Hands's words. I used to have both, I thought. Now I just hope for either.

I didn't say that though. I just stood up and shook hands with the sheik. “Let's move,” I told my soldiers, as Private Smitty scooped up the mortar tube and tripod.

We walked back outside, and I told Staff Sergeant Boondock to load up the local security. I thought about getting back to the combat outpost. The Joes would flock to the phones and to the computers, of course, still connected with the old world, while the NCOs would head to their makeshift poker table, content and comfortable in our new one. I had a patrol debrief to write, but after that, a nap was more than in order.

When I got back to my Stryker and got on the radio, however, SFC Big Country relayed a message from the TOC. They needed us to meet up with a local woman who worried her son had fallen in with a bad crowdâthe insurgent, IED-emplacing kind. She wanted us to talk to him and hopefully scare him out of a future that would lead to American 50-caliber rounds riddling his body. Fuck it, I thought. Anything for a mom.

“White,” I said. “Throw up the hate fist, and let me know when you're redcon-1. We got another follow-on mission.”

“This, uhh, White 2,” Staff Sergeant Bulldog drawled. “We redcon-1.”

“This is White 3,” Staff Sergeant Boondock boomed. “Hate fists are up, and we're redcon-1!”

“This is 4,” SFC Big Country thundered. “Let's move.”

“On your move, 2,” I said, watching the wheels of my senior scout's vehicle churn forward.

This today was just like any other except for the todays that were different.

OLIVER TWISTEDJust another day in the Suck.

Just another day of counterinsurgency tedium, solving a nonconventional, nation-building, political problem with a conventional military used to nation destroying that sometimes forgot it was trying to be nonconventional. Just another day of our dismount teams walking with me between creeping Strykers, winding through the back alleys and alley backs of Saba al-Bor. Just another day of talking to the locals and listening to their multitude of gripes, bitches, and complaints. Just another day of “mistah, mistah, gimmeâ”

Just another day of counterinsurgency tedium, solving a nonconventional, nation-building, political problem with a conventional military used to nation destroying that sometimes forgot it was trying to be nonconventional. Just another day of our dismount teams walking with me between creeping Strykers, winding through the back alleys and alley backs of Saba al-Bor. Just another day of talking to the locals and listening to their multitude of gripes, bitches, and complaints. Just another day of “mistah, mistah, gimmeâ”

“Please, sir, I want some more.”

Last calling station . . . say again? You're coming in lucid and earth-shattering.

I looked down at the originator of the voice. Three Iraqi girls, all with shining black eyes and long black hair, had crowded around me and Suge Knight. They had their hands outstretched, hoping. All three were dressed in pink Barbie sweats caked in months' worth of mud.

“What did you just say?” I asked.

I doubt any of them understood me, as they repeated their original request: “Mistah, mistah, gimme chocolata!”

I shook my head. The sun must be getting to me, I thought. I yelled at one of the gunners to toss down three bottles of water and turned back to the three children. I handed one of the girls a bottle of water, then I handed Suge one, and I kept the third.

“He has chocolata,” I said to the girls, pointing at an oblivious Sergeant Cheech, located twenty feet to our front, peering down an alley. The girls bounded off in the direction of my finger, moving like hunters zeroing in on wounded prey.

“You okay, LT?” Suge asked me. “You do not seem happy.”

I smirked and patted him on the back. “I'm good, man. Drink up, and we'll keep moving. But no Coke!”

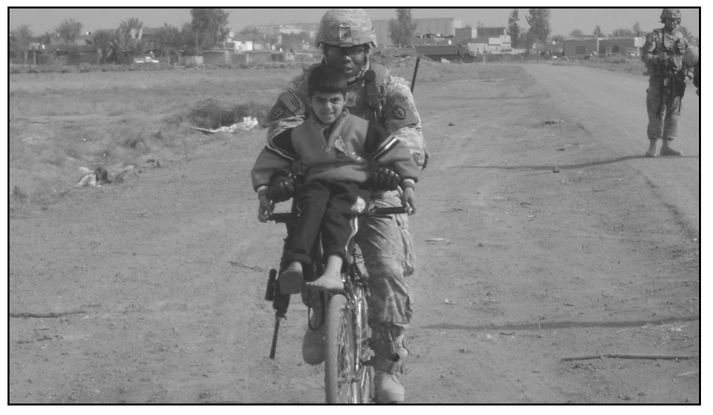

Staff Sergeant Bulldog takes a local Iraqi child for a spin on a commandeered bicycle.

Suge giggled and spoke. “You are good leader of me, LT!” A few days before, I had learned that Suge suffered from diabetes, something he had known about for ten years or so. Such knowledge hadn't stopped his sugar cravings and soda abuse, though, something we were all trying to wean him off of now, for his own good.

I took a swig of cool water, and as it dribbled down my throat, my dismount radio crackled. “White 1, this is White 3.”

I snatched up the hand mic, eager to find out if Staff Sergeant Boondock had discovered something beyond the status quo of disgruntled locals. “Send it, 3.”

“Yeah . . . we have a situation back here. I think you may wanna check it out yourself.”

I glanced over at Suge, who had wandered over to Specialist Tunnel's position to yell at some surly teenagers for failing to produce their ID cards in a timely manner. Artful dodgers, the lot of 'em. Staff Sergeant Boondock was a block over, near a house I had purposely chosen to bypass; some weeks earlier, after putting out a small house fire, we smelled burning fur and went inside the house to investigate. We found the smoldering carcasses of dead dogs scattered across the main room, as lifeless as the Arabian Desert itself. After questioning the neighborhood, we learned that after the fire started,

the locals had hauled the already-deceased wild dogs into the house, hoping to create some sort of roasted meat for food. That was the type of poverty found hereâand why something as simple as a candy bar sent throngs of children into mass hysteria. I didn't want to head back down that street, but if Staff Sergeant Boondockâhe of the “The way out is through” mantraâhad discovered a situation that required the lieutenant's attention, duty beckoned, sensibilities be damned.

the locals had hauled the already-deceased wild dogs into the house, hoping to create some sort of roasted meat for food. That was the type of poverty found hereâand why something as simple as a candy bar sent throngs of children into mass hysteria. I didn't want to head back down that street, but if Staff Sergeant Boondockâhe of the “The way out is through” mantraâhad discovered a situation that required the lieutenant's attention, duty beckoned, sensibilities be damned.

“We're en route,” I said.

In the distance, I spotted yet another mob of Iraqi children serving as brush to the redwoods of American soldiers. Staff Sergeant Boondock's transmission had brought over SFC Big Country as well, but as Suge and I strolled up to their position, they both started to wave us away.

“My bad, sir,” Staff Sergeant Boondock said. “I think I misunderstood the little fucker. His house got blown up last year, but at first I thought he said they still had bombs there. False alarm.”

“Well, we got Suge here now,” SFC Big Country said. “We might as well make sure.” My platoon sergeant had his hand on the shoulder of a young boy with squinty eyes, dirty black locks of hair, and a lackadaisical strut, whom he guided up to our terp.

“You got the condolence funds paperwork in your vehicle?” I asked SFC Big Country. Only Allah knew how this kid's house had really blown up, but we had learned very painfully that the best way to defuse angry Iraqis was to hand them a stack of confusing paperwork that potentially led to financial reimbursement, if filled out correctly. It was like the Victorian-era British Poor Laws or, in more modern terms, what the lady at the DMV did to keep the line moving.

“He say that Ali Baba blow up his house ten months ago,” Suge translated. “It kill his whole family except for him and little brother. He ask for mulasim [lieutenant].”

Corporal Spot, who pulled security away from the Stryker, turned around and shook his head in troubled dismay. Suge continued.

“He say that his brother is at house now. They still live there, and neighbors watch over them.”

“What about the bomb, Suge?” I asked. “Get to the bomb.” I wanted to sympathize with the kid, and I wouldâjust as soon as I got back to the combat outpost and didn't have to worry about snipers turning my head into a passive verb.

Suge nodded at me and switched back to Arabic. The boy responded, and Suge translated again. “He say that there is still bomb in his front yard. He say that his brother stays there to guard it.”

“I knew it!” Staff Sergeant Boondock erupted in passion. “I fucking knew the kid said there was something still there.”

“Where's his house?” SFC Big Country asked.

Suge pointed across the street. “He say his house is right there.” It wasn't near the roasted-dog house, luckily.

I walked up to the boy, putting out my gloved fist so he could pound it. He proved wary of the plastic lining, though, and instead seized my hand and tugged.

“What your name?” he demanded in broken English.

I looked down at the child, amused at his impudence. The cocky Iraqi kids were few and far between, but they tended to be the ones that stuck with you. “Schlonic,” I began, using an Iraqi slang greeting. I pointed at my chest. “My name is Matt.” I pointed back at him. “What is your name?”

He stuck a thumb into my leg, which caused everyone else to laugh, including Suge.

“Maaaahhhhhtttt,” he said, struggling with the terseness of the English vowel. “My name Yusef.”

“Well, Yusef, lead the way,” I told the boy, tousling his hair. As he dashed across his neighborhood, four American soldiers and one terp in tow, his tiny body literally shook with excitement. We followed, wedging out into formation, rifles at the low-ready.

Yusef's houseâor more accurately, what was left of itâhad certainly seen better days. Building rubble and concrete bits of foundation were dispersed around the area the boy led us to, and holes the size of bowling balls perforated the roof. A front stoop led to an entry room that simply wasn't there anymore, leaving a large hole between the last step and the beginning of the house. A small boy with curly black hair, presumably Yusef's younger brother, sat on the stoop to nowhere. His shorts on the right side hung inconclusively off of his right leg; he was missing the foot entirely, and the leg itself was permanently twisted around at a 90-degree angle just below the knee. The right side of his face was covered in dark pink scars, starting at his hairline and jutting downward, across his cheeks, to the top of his chin. We waved at him, but he continued to stare vacantly at the ground directly in front of him, indifferent to our mission.

Other books

The Lure of White Oak Lake by Robin Alexander

Dog Years by Gunter Grass

I Am Regina by Sally M. Keehn

Breaking Free by Teresa Reasor

The Language of the Dead by Stephen Kelly

Bed of Bones (A Sloane Monroe Novel, Book Five) by Cheryl Bradshaw

A Cure for Suicide by Jesse Ball

The Spirit of Revenge by Bryan Gifford

The House of Dolls by David Hewson

Pigeon Feathers by John Updike