Kaboom (19 page)

Authors: Matthew Gallagher

At least the children had an excuse for their simplicityâthey were in elementary schoolâand at least they wrote us in crayon, which the nonconformist in me appreciated. Further, gems could be mined out of these letters with stunning regularity; in a postmodern world addicted to irony and understatement,

nothing could have been a more authentic reminder of home. Real American children wrote these real American letters with real American crayons, and the Gravediggers collectively gathered them up in the winter and spring of 2008:

nothing could have been a more authentic reminder of home. Real American children wrote these real American letters with real American crayons, and the Gravediggers collectively gathered them up in the winter and spring of 2008:

I hope you don't die, soldier. That would be bad.

I feel sorry for you.

I think war is worse than math.

My daddy doesn't want me to be in the soldiers, 'cause he says that the Irack will last forever. Maybe if he changes his mind I'll see you in the Irack.

My cousin was in war but he got hurt. Now he has a big beard and drinks beer all day long. My mom says he should get a job.

Can you send me back a bad guy's head? That would be cool.

I'm going to study real hard, so I don't have to go to Iraq. Do you wish you had done better at school?

I hate cursive. Do you have to write in cursive for war?

Is it like the movies? Do our letters make you feel better?

The letters did make me feel better. I always meant to write that kid back and tell him so. I never got around to it. I still don't know why.

UNDER THE CRESCENT MOONWe slipped out under the

crescent moon, carefully treading through the midnight blackness, and adjusted to our night-vision devices while locking and loading our M4s. Shades of green ebbed and flowed before our eyes, in a hallucination of amorphous haze. I uttered a quick message to our headquarters over the radio, letting them know that we were departing, and followed the shape in front of me disappearing into the dark horizon.

crescent moon, carefully treading through the midnight blackness, and adjusted to our night-vision devices while locking and loading our M4s. Shades of green ebbed and flowed before our eyes, in a hallucination of amorphous haze. I uttered a quick message to our headquarters over the radio, letting them know that we were departing, and followed the shape in front of me disappearing into the dark horizon.

“Sir?” PFC Das Boot said from behind me, as I moved away from both him and the radio on his back.

“What's up?”

The young private's German accent crackled. “Staff Sergeant Boondock told me to stay ten steps behind you. Is that okay for you for when you need me to bring up the radio?”

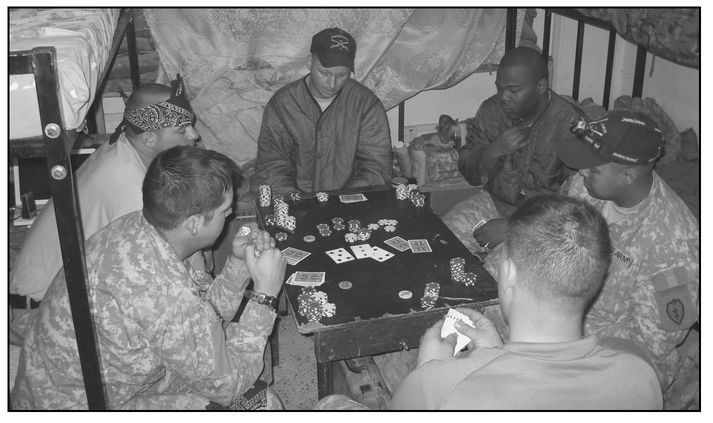

A group of Bravo Troop NCOs unwind over a game of poker at the Saba al-Bor combat outpost. Due to an intense operation tempo, soldiers at combat outposts rarely made it back to the large forward operating bases, where comforts like hot showers and fast food were found.

“That's fine, man. That's fine. I'll let you know when I need you.”

I turned back around. Sergeant Cheech took the point position for that night's patrol, and the platoon fell into a staggered column behind him without a pause. Staff Sergeant Bulldog's Alpha section moved in front of me, while Staff Sergeant Boondock's Bravo section moved behind me.

Better keep up, the doubting part of me thought.

Don't worry about that, responded my cocky side.

Few experiences in my life were as eerie as a late-night dismounted patrol through Saba al-Bor. Fear played a part of it, admittedly. Nerves, too. There were bits of excitement as well. Sensual overload ensued every timeâevery sense churned away on the fumes of our remaining wits to keep us alert, with every turbo button in our brains being mashed over and over again to keep us moving.

I saw the smoke from burning tires smoldering away all over the town. I smelled the raw sewage toxins so prevalent in the southern sector. I heard the insurgency of barking wild dogs chronicle every explicit detail of our winding movements. I touched Suge Knight's shoulder next to me to guide him through the dark as he leaned over to whisper about the historical significance of the Prophet Muhammad's grandson, Husayn, while we passed

a Shia mosque towering alone in no-man's-land. I tasted cool, bracing water from my CamelBak as it rushed into my dry throatâand I walked, and then I walked some more. Throughout, I exchanged various hand-and-arm signals with my men to my front and to my rear.

Stop. Take a knee. 360-degree security here. Linear danger area ahead. Bring up the lieutenant. Send an update back to SFC Big Country and Bravo section. Keep moving

.

a Shia mosque towering alone in no-man's-land. I tasted cool, bracing water from my CamelBak as it rushed into my dry throatâand I walked, and then I walked some more. Throughout, I exchanged various hand-and-arm signals with my men to my front and to my rear.

Stop. Take a knee. 360-degree security here. Linear danger area ahead. Bring up the lieutenant. Send an update back to SFC Big Country and Bravo section. Keep moving

.

While we were impressed with our stealthâas were the various groups of locals we snuck up on, shocking them into quiet conciliation while they huddled around burning tires and newspapers for warmthâwe were certainly no Delta Force, and missteps occurred during the opening minutes of our patrol. Some of the younger soldiers in front of me began to bunch up the formation, seeking out subliminal comfort with closer proximity to another human being. Staff Sergeant Bulldog quickly remedied this, however, maneuvering through his section with a hammer's grace, physically moving the Joes back to their proper place and distance. A few minutes later, I saw a bodyâI registered the stocky cut and hasty strut as PFC Smitty'sâfall over a curb some ten feet in front of me, stagger up, and follow that with some muffled expletives. I smiled, something that inevitably brought on the god of karma, and I immediately fell myself.

“Mother fucker,” I hissed, as I stood back up, holding my rolled ankle, cursing at the terrorist hole that had seized my leg, instantly more sentient to the additional weight compressed around my chest in armored plates and various gear additions. “Stupid-ass country and its stupid-ass bullshit.”

“What?” Suge asked. “Are you okay, Lieutenant?”

“I'm fine,” I growled, temporarily livid that a near-blind terp with a slight hobble and without the benefit of night-vision goggles somehow managed never to fall.

The hand-and-arm signals continued.

Keep moving. Stop. Take a knee. Crossing a linear danger area. Bring up the LT.

Keep moving. Stop. Take a knee. Crossing a linear danger area. Bring up the LT.

I sauntered up to a Sons of Iraq checkpoint, while my soldiers fanned out around me, posting far-side security. A group of Iraqi men gathered around a small fire, AK-47s hanging loosely from their backs, all sporting matching khaki hats and khaki jackets.

“We got four of 'em, sir,” Private Romeo said back to me, as he moved to his far-side position.

“Schlonic,” I said, hand raised.

“Hello, mistah!” they responded, trying to act as awake and as alert as possible, scrambling up to shake my hand. We'd snuck up on them by emerging

silently out of the shadows of the night, surprising them by not rolling past in our monstrous Strykers first. They knew that they should be closer to the street in order to stop any late-night traffic that came by. They also knew that there should have been six Sahwa working at this hour at this checkpoint.

silently out of the shadows of the night, surprising them by not rolling past in our monstrous Strykers first. They knew that they should be closer to the street in order to stop any late-night traffic that came by. They also knew that there should have been six Sahwa working at this hour at this checkpoint.

“Where are the other two?” I didn't feel like dealing with the normal bullshit and glad-handing. Suge's voice matched mine in both pace and tenacity; this was his fourth year of interpreting, and I was his seventh lieutenant. His English may have been shoddy at times, but his understanding of American standard operating procedures and platoon leader moods was not.

A rapid flurry of Arabic words emerged posttranslation. “Don't bullshit me,” I warned, not bothering to wait for Suge. I'd had this discussion and heard these excuses before.

After a pregnant pause, one of the Sons spoke to Suge. “He say that the other two are sick, and they were unable to find new guys,” Suge translated, voice dripping with disgust.

I smiled to myself. This bothered him more than it did me. I pulled out my notebook and red lens flashlight and wrote with great demonstrative flair. “Tell them we'll be letting their sheik know about this and that Captain Whiteback will be docking their pay. Again.”

Keep moving. Stop. Take a knee. 360-degree security here. Linear danger area ahead. Bring up the LT. Talk to the Sons of Iraq. Keep moving. Send an update back to SFC Big Country and Bravo section. Keep moving. Stop. Take a knee. Keep moving.

We now walked Route Swords, south to north, staggered column intact, silence assured. The mental tracker I kept in my mind placed our positions just short of Sheik Banana-Hands's palace. I impulsively checked my watch; it'd been three hours since we left the combat outpost. I chided myself for letting my mind wander over the course of the patrol, thinking about things and people and dreams that were left in the old world instead of concentrating solely on the mission at hand. It wasn't going to be like it had been, anyway, I reminded myself. Or how I wanted it to be. Or how it should have been. Why bother.

I heard shouts in Arabic to my front, and the sound of an AK-47 cocking reverberated in the still of the night. My men immediately dropped to the ground and sought out whatever cover they could find. I spied PFC Cold-Cuts just ahead of me huddling behind a generator, and Specialist Flashback across from me rolled into a ditch on the side of the road. I'd moved to my left, found myself kneeling in the door frame of a store, and felt Suge behind me, crunched

over in the same position. Twenty M4 Carbine rifles were wedged tightly into shoulder pockets, oriented systematically to our north, night-vision lasers dancing around multiple shadows and shapes that resembled human silhouettes.

over in the same position. Twenty M4 Carbine rifles were wedged tightly into shoulder pockets, oriented systematically to our north, night-vision lasers dancing around multiple shadows and shapes that resembled human silhouettes.

“Hey, mutha fucka!” Staff Sergeant Bulldog yelled somewhere to my front right. “We Americans, who's you is?” Positive identification of the enemy. That was all that any of us wanted.

It must be Banana-Hands's bodyguards, I thought, wandering on their own dismounted patrol. It's got to be. No one else would be down here at this time of night. If they weren't his bodyguards, they would have shot already. Unless they hadn't seen us yet. I refocused my night vision. Three green blobs, all standing up and holding rifles, paced frenziedly, heads scanning for our movements.

I heard Staff Sergeant Bulldog yell again in the direction of the green blobs, and I figured he thought the same thing about their being Sahwa bodyguards. I remembered that Arabsâbe they Sahwa, terps, terrorists, or bumsâstruggled with Staff Sergeant Bulldog's Southern accent and didn't think he was speaking English. I needed to execute a shitty plan quickly rather than wait for the perfect one to develop.

“Let's go, Suge,” I said, walking into the middle of the street.

“Salaam aleichem!” I yelled. “Americans!” I injected as much nasal white-bread suburbanite as I could into my voice for clarity's sake. I also swung my rifle back down into the low-ready and began to stroke the safety trigger. If they started shooting at me, I figured at least my soldiers would finally have the positive identification they'd been aching for.

On my fourth step forward, I saw the green light of God, a powerful naked-eye laser, shine by me and center directly on an Iraqi's foreheadâSergeant Spade's own way of telling the mystery men that we were Americans ready and willing to turn their lives Jurassic. That'll work too, I thought.

I continued walking and came up on three frozen members of Sheik Banana-Hands's bodyguard posse. They stuttered their way through a conversation, filling it with apologies, explanations, and offers of chai. I made them clear their weapons, and we kept moving.

I looked over at Suge, who shook his head. “Stupid men do stupid things,” he said.

“Are you talking about me or them?” I asked.

He laughed. “Them, of course! You are the lieutenant. You are smart. Sometimes crazy, yes, and you don't always listen to me, Suge Knight, when you should, but you are very smart.”

I wasn't sure if he had complimented me or not, so I kept my mouth shut.

We walked around a corner and started moving back west. The bright lights of the combat outpost shined in the distance, washing out my night vision. Like a proud citadel rising out of medieval lowlands, our home contrasted starkly with the dirty paucity we now trudged through. I felt my pace quicken slightly, with the visual promise of our mission's end and the simple pleasures that came with it.

Ten minutes later, I counted my soldiers in through the T-wall barriers. Twenty out, twenty in. End of mission. SFC Big Country brought up the rear of our patrol, ensuring that no one strayed from the pack.

“Another productive mission,” I said, my words laced with undertones.

He looked down at me, grabbed my shoulder for leverage, and began to stretch his legs. “Hell, sir,” he said, “we all made it back. That's the most important thing.”

When he finished stretching, we took a seat on the front stoop. I accepted his offer of a cigarette and took a quick drag. I coughed but did my best to muffle it. I still didn't get a buzz from tobacco, but it usually made the headaches go away.

“You're right, of course,” I told my platoon sergeant after a few minutes of silence. “That is the most important thing. Mission accomplished.” I paused melodramatically. “Think we'll get a banner?”

He laughed and said no, probably no banner. I looked up at the moon, which still grinned madly. We would sleep before it did. I took another drag from my cigarette and watched smoky embers rage into nothingness on the concrete. Then I walked inside, eager to shed my body armor, hoping that our patrol had tired me out enough that I would be able to sleep instead of think about things beyond my control.

Other books

The Bureau (A Cage for Men and Wolves Book 1) by Michelle Kay

Heart of the Country by Tricia Stringer

Subtle Bodies by Norman Rush

Unleash Me, Vol. 1 (Unleash Me, Annihilate Me Series) by Ross, Christina

Obsessive by Isobel Irons

A Little Texas by Liz Talley

The Forgotten Founding Father- Noah Webster by Joshua C. Kendall

The Straight Crimes by Matt Juhl

A Mistletoe Proposal by Lucy Gordon

The Denver Cereal by Claudia Hall Christian