Keeping Score (3 page)

Authors: Linda Sue Park

Joey-Mick played second base, same as his favorite player, Jackie Robinson. And if he got to first when he was at bat, he would move around on the base pathâhopping, prancing, faking a stealâjust like Jackie.

Last season, when Maggie first started listening to the Dodger broadcasts

âreally

listening to them, paying attention, learning the gameâshe decided that Jackie Robinson was her favorite player, too.

Not

because she was a copycat. Or because he was the first-ever Negro in the league, which everyone knew was a big deal. So big that even though Dad was a Yankees fan, he was a Jackie Robinson fan, too. "Biggest thing that's ever happened in baseball" was how Dad put it.

But Maggie had been only five years old when Jackie broke in, and she hadn't understood very much about baseball back then. So she didn't have any real memories of his first year with the Dodgers. And now, four years later, almost every team had Negro ballplayers.

No, it was the

spark

Jackie had, how he seemed to light up the whole game when he was on the field. So she told Joey-Mick that Jackie was her favorite player, too.

"No dice," Joey-Mick said immediately.

"Why not?"

"'Cause he's

my

favorite player. We can't both have

him as our favorite player, and I had him first. So you gotta pick someone else."

"But why can't both of usâ"

"Because," he said firmly. "Now, who's your second-favorite player?"

Maggie hesitated. She still wanted Jackie, but it was an interesting question. "Pee Wee," she said. "No, wait. Roy Campanella."

"See, there you go. One of them's can be your favorite player."

She had chosen Campy in the end, which was no shameâhe was terrific, both at the plate and behind it. But she didn't feel the same way about Campy that she did about Jackie. She wondered why she hadn't fought harder. Joey-Mick wasn't in charge of the world. Since when did he get to decide favorite-player rules? But if she had stuck with Jackie, her brother would think she was copycatting, no matter what she said.

Joey-Mick slammed the door on his way out. Maggie sighed and tugged at the collar of her dress so she could blow down the front of it. Then she wandered into the kitchen, opened the Frigidaire door, and took out a bottle of milk. Not to drink, but so she could press the cool glass against her forehead.

"Put that back," Mom said automatically without even looking up from the onion she was chopping. "And I'll go to my grave telling you to keep the Frigidaire door closed!"

Maggie put the bottle back on the shelf. She let the door swing shut and made sure to stand right where she could feel the last puff of lovely cool air.

"What's for supper?" she asked, more out of boredom than curiosity.

"Sausage and macaroni," Mom answered. "It's Wednesday, so it is."

Monday, Wednesday, and Friday were macaroni nights. Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday meant potatoes. Sundays alternated. That was how it had been ever since Maggie's parents got marriedâRose Fitzpatrick and Joe Fortini, Irish and Italian. The only time the pattern was interrupted was when one of the uncles came for dinner. If it was Uncle Pat, Mom cooked potatoes no matter what day it was; for Uncle Leo, macaroni. Maggie liked both potatoes and macaroni, and she was glad she didn't have to eat just one all the time. At Treecie's house they almost always had potatoes.

Mom nodded toward a plate on the countertop. "There," she said, "for that dog friend of yours." And she pointed the tip of her knife at the naked bone that had already done double-duty in Sunday's roast and Monday's soup.

Maggie gave Mom a hug. "Thanks," she said.

"Oof. Don't be hanging on to me in this heat. Go on with yourself now."

Maggie smiled as she took the bone and left. Mom wouldn't have a dog in the house, but a week never went by that she didn't have a little something for Maggie to give Charky.

The dog greeted her as usual, half a block from the

firehouse. Maggie made him sit, beg, and speak before she gave him the bone. He hurried back to the station, looking over his shoulder as he loped along, to make sure she was following.

When Maggie got near the firehouse, she could see the new guyâJim, she reminded herself, Jim Maineâsitting out front with his radio. The Giants' game. Nobody else was around; the other guys were probably inside.

Jim had a notebook on his lap and was writing in it. He didn't look up when Charky bounded past and went to his bed, where he lay down, gnawing joyfully.

Jim seemed very busy with whatever he was working on. It would probably be rude to interrupt him. Maggie turned to leave.

"

...and Mays rounds thirdâhe's going to try to score! The throw comes inâhe slidesâthe ump ... SAFE! HE'S SAFE! He's in under the tag! Mays has just scored from first base on a single! Howdya like that!?

"

Jim let out a whoop and raised his arms in celebration. That was when he saw Maggie.

"Hey there!" he said.

"Hi. I justâI brought a bone for Charky."

Jim turned around to look at the dog and grinned. "Lucky dog," he said. "Say, did you hear that last play? Wasn't that something?"

Maggie nodded.

Jim shook his head, still smiling. "It's gonna seem like a mistake," he said. "Later, if anyone sees this, they're gonna think I left out a playâa throwing error or something." As he scribbled in the notebook, his voice lowered, so he seemed to be talking to himself, but Maggie could still hear what he was saying. "Scoring from first on a single ... drew the throw too, so now they got a runner on second."

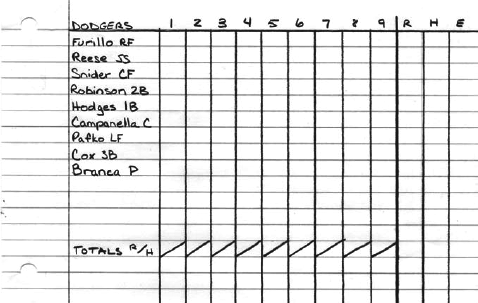

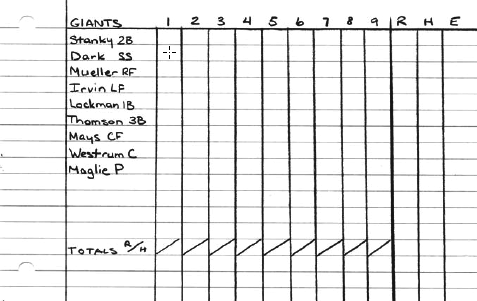

Maggie took a step closer and tilted her head so she could read sort of sideways rather than upside-down. There was writing on both pages of the open spread, and a lot of little squares filled with tiny numbers and letters and lines. In a column on the left side of each page, Jim had written the names of the playersâthe Cubs on one page, the Giants on the other.

"What's that you're doing?" Maggie asked.

"You never seen anyone keep score before?"

She shook her head. "What do the numbers mean?"

His eyebrows went up. "It's kinda complicated," he said. "I dunnoâoh, hold up a minute."

The next batter hit a hard liner caught by the shortstop, who then beat the baserunner back to second: Unassisted double play to end the inning.

Jim shook his head. "Great play," he said ruefully as he wrote something down. "Okay, where was I? The numbers. Well, for a start, you gotta know the game pretty good."

Maggie stuck out her chin. "I know the game just fine."

Jim stared at her for a moment, then grinned. "Wouldn't doubt it, you being Teeny Joe's kid. Even seeing you're a girl. But lemme see you prove it."

"How?"

"Well ... okay. What was so special about that scoring play just now?"

Maggie shrugged. "Nobody hardly ever scores from first base on a single," she said, with a bored little drone in her voice, as though she was reciting a lesson at school. Who did this guy think he was, quizzing her on baseball? "Depending on where it's hit, you usually only get to second, but if it's hit to right field and you got good speed, you could maybe get to third, but if the right fielder has a strong arm it'll prob'ly be a close play, so for him to make it all the way homeâhe musta had a big jump on the pitch, or maybe the hit-and-run was on, and thenâ"

Jim held up his hands, laughing. "Okay, okay! Wow, you oughta be on the radio your own self! The thing is, keeping score, you gotta be more than just a fan...."

His voiced trailed off. He was looking at her hard, his head tilted and his eyes narrowed, but there seemed to be a twinkle there, too. Maggie looked right back at him and kept her chin high, but inside she squirmed a little. It was like he was trying to see right inside her brain.

Jim seemed to make up his mind. He handed her the notebook and pencil, then went inside the bay doors to fetch another folding chair, which he set up next to his own.

"Sit," he said. "Easiest way is if you watch while I do it. If you're really interested, you'll pick it up on your own, most of it anyhow, and I'll explain the rest."

By the end of the game, Maggie knew how the defense was numbered. Not their uniform numbers, but their

position

numbers. Jim tore a sheet out of the

back of the notebook so she could write it down to study at home.

1 â pitcher

2 â catcher

3 â first base

4 â second base

5 â third base

6 â shortstop

7 â left field

8 â center field

9 â right field

Jim also showed her what the numbers in the little squares meant. They told what each batter had done. "4-3" written in the square opposite the batter's name meant that a ground ball had been hit to the second baseman (4) who had thrown it to the first baseman (3) for the out.

Jim could look at his score sheet and see exactly what had happened in any inning. Which was way better than just keeping it in your head, because when you were trying to remember what happened in a game, only the big exciting plays came to mind. But Maggie knew that baseball was often a game of little thingsâthe pitcher falling behind in the count, the good throw to keep a runner from advancing, the slide to break up a double playâand those were hard to keep track of. Jim's score sheet didn't have every single thing written down, but the things that were there could really help you remember.

"Can I come again tomorrow?" she asked. "Will you show me some more?"

"Sure," Jim said. "Tomorrow's a night game. I'm off-duty, but I'll meet you here anyway. If your ma says it's okay."

Maggie let her eyes twinkle at him. "I'll ask my dad."

"Ha! Okay, Miss Maggie-o. And one other thing. Dodgers play tomorrow night too, but we'll be listening to the

Giants'

gameâgot it?"

"That's all right," Maggie said. She knew the Dodgers would be on the other radio; she could find out the score whenever she wanted. Then she frowned. "But that means we'll have to have your radio turned up, won't we? So we can both hear it? The other guysâ"

"Hmm." Jim looked thoughtful. "Yeah. Well, I'll figure something out. You just worry about learning those position numbers, okay?"

Maggie trotted home after giving Charky a hug. She already knew that she wasn't going to tell Joey-Mick about learning how to score a game, not yet. Not until she could do a whole game all by herself. Maybe she would just sit there in front of the radio, writing stuff down, and when he asked what she was doing,

then

she would tell him.

She might even teach him, too. If he asked very nicely.

Jim had brought a long extension cord to the firehouse so they could put his radio on the sidewalk a good few

yards away from the drive. George expressed both astonishment and disapproval over Maggie's listening to the Giants' games, but she assured him it was only so she could learn to keep score herself, "and then I'll be doing the Dodgers' games, okay, George?" He had given his grudging approval. Not that she needed it, but she didn't want him to be mad at her.

So much to learn about keeping score! Maggie was torn between wanting to know all of it

now

and the fun of discovering a new thing or two or three every day.

Jim showed Maggie how to list the batting order, each team on a separate page. Then you wrote the inning number, one through nine, across the top, and drew lines down the page to make narrow columns for each inning. Those vertical lines and the pale blue horizontal lines printed on the page formed boxes, each no bigger than her thumbnail.

When a player batted, you wrote the play down in the little box opposite his name, in the column for the correct inning. Special numbers and letters were used for different plays. For example, Jim taught her that "K" stood for strikeout. There were two ways for a player to strike outâby swinging and missing, or by

not

swinging at a pitch that was called a strike by the umpire. For a swing and a miss, you wrote a normal K. But for a called strike, you used a backward one: K.

It was a handy way to tell the difference, but more than that, Maggie loved how the backward K looked so strange on the pageâaskew and confused, just like a batter befuddled by a pitch.

"Strikeout looking is worse than strikeout swinging," Maggie declared. "At least swinging, you know the guy tried."

"Yeah," Jim agreed, "except when the ump makes a bum callâwhen it shoulda been a ball."

A strikeout was easy to record, just one letter. But for some plays, Maggie had to squeeze a lot more into the little square. Like "6-4-3" for a double play when a ground ball was hit to the shortstop, who threw to the second baseman, who threw to the first baseman.

It was often a pure aggravation trying to make it all fit. Good thing for Maggie that penmanship was one of her best subjects in school. She discovered that it helped to have a really sharp pencil, so she bought a nickel sharpener from Mr. Aldo at the corner store and carried it around in her pocket.