Kennedy: The Classic Biography (77 page)

Read Kennedy: The Classic Biography Online

Authors: Ted Sorensen

Tags: #Biography, #General, #United States - Politics and government - 1961-1963, #Law, #Presidents, #Presidents & Heads of State, #John F, #History, #Presidents - United States, #20th Century, #Biography & Autobiography, #Kennedy, #Lawyers & Judges, #Legal Profession, #United States

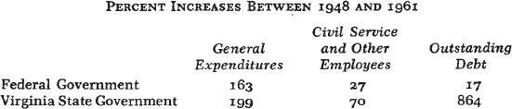

But his favorite comparison of all, not surprisingly, was with the fiscal record of his Republican predecessor. On occasion he would ask visitors: considering Truman’s expenditures in Korea and at the end of the Second World War, how do you think Eisenhower’s eight budgets compared with Truman’s eight budgets? No one ever came close to the correct answer: Eisenhower outspent Truman by $182 billion. “You could win a bet on that in any bar in the country,” the President told me when I first gave him the figure. He would also cite Eisenhower’s record of five deficits in eight years, including an all-time peacetime high of $12 billion, the $23 billion Eisenhower added to the national debt and the 200,000 civilian employees he added to the Federal payroll. All Presidents, Kennedy would then continue, outspend their predecessors in a growing, progressive nation. Eisenhower’s Budget Director had issued a study forecasting continued Budget increases regardless of the party in power. The Kennedy administration’s “domestic” increases, which were less than a quarter of his new expenditures, didn’t sound so outrageous when shown to be less than in the last three years of his predecessor.

However, despite criticisms from the left that he ought to be spending much more, the President recognized that comparatively few of the voters who were concerned about too much spending, and who read publications concerned about too much spending, would ever regard him as more thrifty than Eisenhower. He tried. He asked the Council of Economic Advisers and Budget Bureau to prepare detailed answers to inaccurate editorials on his fiscal policies in

Life

and the

Reader’s Digest

, calling one of Walter Heller’s assistants at home one Sunday afternoon to ask questions on each line in the latter’s suggested reply. He commented in a news conference on the failure of the press to assist his fiscal re-education program, with almost all newspapers persisting in repeating the same clichés about rising outlays, debt and payrolls, instead of the declining ratio of those figures to the national population and output. “One of the reasons we have such difficulty getting an acceptance of our expenditures and our tax policies,” he said, “is because people misread the statistics or are misled.”

3. The third and final approach to obtaining a more sophisticated understanding of debt and budget problems was the most direct: to impress upon the public, without comparisons or contrivance, the necessity and desirability of not only the increases in his Budget but the increases in the deficit. Each year his Economic Report grew a little bolder along these lines. In 1961 one had to look hard to find in his Message on Economic Recovery the conclusion that “deficits accompany—and indeed help overcome—low levels of economic activity.” But by 1963, dropping any pretense of offering a balanced Budget, he was more boldly pointing out—even in a speech to the nation’s editors, the watchdogs of our fiscal integrity—that “carefully screened and selected Federal expenditure programs can play a useful role, both singly and in combination; to cut $5-10 billion [from the Budget], unless the private economy is booming…would harm both the nation and the typical neighborhood in it.”

He reminded several audiences of Eisenhower’s experience in 1958—that trying to cut back expenditures to fit revenues meant contract cancellations, payment stretch-outs, grant-in-aid suspensions, employee layoffs, and thus less taxable income, more outlays for the jobless and still more Budget deficits. Over and over he stressed that point: it is unemployment and recession that cut revenues and produce deficits.

He tried to get people to think about what the Budget is, what their money goes for. “The Federal Government is the people…not a remote bureaucracy,” he said, “and the Budget is a reflection of their needs…. To take the expenditures required to meet these needs out of the Federal Budget will only cast them on state and local governments”—and they are doing worse fiscally.

In a chart session with Congressional Democrats in January, 1963, he showed that four-fifths of his Budget increases had gone for defense, space and the cost of past or future wars—that the Budget represented not a bureaucratic grab but loans to farmers and small businessmen, aid to education and conservation, urban renewal and area redevelopment. Using similar charts in a talk to the editors, he used an imaginary cross-section community, “Random Village,” to illustrate how all families are benefited by Federal programs. He spoke to bankers, students, labor groups, business groups, economists and others in his effort to put across the facts of economic life.

He also encouraged articles on the need for spending and encouraged his economic advisers, Treasury Secretary and Budget Director to talk plainly. Heller, by testifying in 1963 that popular opposition to tax cuts must be due partly to a “basic puritan ethic,” invited the delightful riposte by one Republican that he’d “rather be a Puritan than a Heller.” New Budget Director Gordon, in office only five weeks, testified that deep cutbacks in Federal spending would reduce prosperity, profits and employment but not the deficit, and Harry Byrd promptly called for his dismissal. “I must have set some kind of record,” Gordon wryly told the President, to have invited ouster demands so quickly. But even earlier the President’s leading Republican adviser, Secretary Dillon, had, to the dismay of his former colleagues in the GOP and on Wall Street, stated the need for deficit financing to treat economic slack, a truth which even previous Democratic Secretaries of the Treasury had been consistently unwilling to acknowledge.

THE 1962 PAUSE

The economy, which had expanded vigorously in 1961, slowed its pace in mid-1962. The growth continued but the zip was gone, and some of the figures were disturbing. The rate of private inventory accumulation—which had been built up to an abnormally high level of seven billion dollars in the first quarter, partly because a steel strike was anticipated—fell off to one billion in the third quarter. Unemployment leveled off at an uncomfortable 5.5 percent. Consumers were saving more instead of spending. Business investment in new plant and equipment, for which the tax credit had not yet been enacted, was low.

The most dramatic cause for concern was a severe drop in the stock market. After reaching a peak on December 12, 1961, the average price of stocks bought and sold on the New York Stock Exchange declined by roughly one-quarter, and roughly one-quarter of this drop occurred on Monday, May 28. It was only the twenty-fourth largest proportionate drop in market history. But it was the sharpest one-day drop in the number of points on the Index since the crash of 1929, and immediately fears and rumors arose—and in some quarters were inspired—that it was 1929 all over again.

Time

magazine speculated on Kennedy becoming “the Democratic version of Herbert Hoover.” Wild stories spread that the decline was due to a business plot to hurt Kennedy, to a European withdrawal of funds or to Kennedy’s attack on Big Steel. Some said it was a once-in-a-generation break, others said that it was due to increased competition from Europe, others attributed it to excess capacity in our sluggish economy.

The simplest explanation to many businessmen was that Kennedy was against profits and free enterprise. His mail and press were filled with blame for “the Kennedy market.” “I received,” the President noted a year later when the market was setting record highs,

several thousands of letters when the stock market went way down in May and June of 1962, blaming me and talking about the “Kennedy market.”…Now that it has broken through the Dow-Jones average…I haven’t gotten a single letter…about the “Kennedy market.”

Harried stockbrokers who found their customers taking their money elsewhere were busy looking for a scapegoat. And, in what even the financial community’s idol, William McChesney Martin, Jr., termed “childish behavior,” many brokers and businessmen placed sole blame upon the President.

They had few facts to support them. Those who blamed it on his steel price fight of early April neglected to mention that the decline had begun back in December, that the ratio of advances to declines had been adverse since the previous August and that stock values in many of the basic industries had been going down for several years. Those who blamed it on Kennedy’s policies neglected to mention that the decline had merely brought prices back to where they stood on the day of his election. Those who said it was a certain sign of recession neglected to mention that the thirteen such drops since the thirties had not even all preceded, much less produced, a recession and that, on the contrary, a sharper drop over a shorter period in May, 1946, had been followed by record-breaking prosperity. Those who compared it to 1929 neglected to mention the fact that the earlier crash had been twice as large and twice as fast in a much smaller economy, preceded by months of declining business and construction, and aggravated by uncontrolled speculation, questionable brokerage practices, a recession in Europe and a lack of Federal floors beneath the economy such as unemployment compensation and insured bank deposits.

Nevertheless the highly publicized break in the market, and the three days of gyrations and four weeks of sag that followed, seemed certain to disturb business and consumer spending. The President called an emergency meeting for May 29 in the Cabinet Room. It was not a cheerful way to spend his forty-fifth birthday. But somewhat to his surprise, he found Dillon, Heller, Federal Reserve Chairman Martin and the other economists present generally unperturbed. The critical loss of confidence, they said, was in the market, not in the economy or even in the administration. Most financial analysts had been predicting for some time that stock prices could not long continue to rise further and faster than potential profits, reaching paper values twenty or more times their earning power. But too many investors, large and small, had been bidding prices up and up, not out of an interest in dividends or corporate ownership, but out of a desire for tax-favored capital gains in an inflationary economy. Now inflation was over, a fact for which the steel price rescission may have served some as a reminder. Once investors started weighing the actual earning power of their shares instead of hoping for continued price rises, many of them realized that bonds and savings banks offered a better return on their money than overpriced and risky stocks. This long-expected downward re-evaluation, the President was told, while temporarily worsened by speculation and its own momentum, would in the long run put the market on a sounder basis.

3

But the President expressed concern in our meeting about the market continuing to fall and dragging the economy down with it. Essentially, in addition to pressing for pending economic legislation, three new courses of action were considered:

1. First was a Presidential “fireside chat” to reassure the nation, to place the market drop in perspective, to review the basic strength of the economy, to contrast the situation with 1929 and to call for calm and confidence. But after work on a possible speech was well under way, this course was suspended, to be revived only if selling went completely out of hand. Stocks were gyrating up, down and up again. Less than 2 percent of the total volume of stock was actually being sold by panicky or margin-called owners, and a nationwide television speech might only spread their panic to others. By staying out of it, by keeping calm, the President hoped to help spread calm, and in time turn the paper losses of the 98 percent who held on into actual gains. He decided, as a “low-key” substitute, simply to open his press conference on June 7 with an over-all look at the economy, using a very mild and very brief analysis of the stock market as a springboard for a review of his program.

2. The second possible action considered that Tuesday was to lower the “margin requirement,” the percentage of actual cash which a stock buyer must put up when he buys on credit. No legislation, only a change in Federal Reserve regulations, was required to reduce this cash requirement from 70 percent, where it then stood, to 50 percent, thus enabling and encouraging more investors to buy more stocks.

The Council of Economic Advisers favored an immediate reduction, partly as a demonstration of Presidential determination (although, due to the peculiar status of the Federal Reserve Board, the President could only request, not direct, the Board to do anything). But there was no evidence that a lack of credit was the market’s immediate problem, and it was agreed by the others that any immediate move might be interpreted as an admission of serious trouble. Instead, margin requirements were quietly lowered to 50 percent some six weeks later, and by late October the market had started booming again, soaring a year after the May scare back up to its December, 1961, high, from which it continued to rise.

3. The third proposal considered in our May 29 meeting, which was considered throughout the balance of the summer, and which related more to the general economy than the stock market alone, was a “quickie” income tax cut of $5-10 billion. It was to apply to both individuals and corporations, and last one year or even less. The Council of Economic Advisers was for it, unless the economy improved. Secretary Dillon was against it, unless the economy worsened. The President reserved judgment until he saw which way the economy moved. Another meeting was scheduled for one week later, and similar meetings were held regularly throughout the summer.