Read Killing Jesus: A History Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly,Martin Dugard

Tags: #Religion, #History, #General

Killing Jesus: A History (22 page)

However, if Jesus is not the Christ, he will die.

Either way, Judas’s life will be spared.

Judas and Caiaphas make the deal. The traitorous disciple promises to begin searching immediately for a place to hand over Jesus. This will mean working closely with the Temple guards to arrange the arrest. He will have to slip away from Jesus and the other disciples to alert his new allies of Jesus’s whereabouts. That may be difficult.

Thirty silver coins are counted out before Judas’s eyes. They clang off one another as they fall into his purse. The traitor is paid in advance.

Judas walks alone back to Bethany. Robbers may be lurking on the roads. Judas wonders how he will explain his absence to Jesus and the others—and where he will hide such a large and noisy bounty.

But it will all work out. For Judas truly believes that he is smarter than his compatriots and deserving of reward in this life.

If Jesus is God, that will soon be known.

The next few hours will tell the tale.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

LOWER CITY OF JERUSALEM

THURSDAY, APRIL 4, A.D. 30

NIGHT

Jesus has so much to do in a very short period of time. He must at last define his life to the disciples. As the final hours to Passover approach, Jesus plans to organize a last meal with his followers before saying good-bye, for they have been eyewitnesses to his legacy. And he must trust them to pass it on.

But although these things are vitally important, there is something holding him back: the terrifying prospect of his coming death.

So Jesus is having trouble focusing on his final message to the disciples. Like every Jew, the Nazarene knows the painful horror and humiliation that await those condemned to the cross. He firmly believes he must fulfill what has been written in Scripture, but panic is overtaking him.

It doesn’t help that the entire city of Jerusalem is in an anxious frenzy of last-minute Passover preparation. Everything must be made perfect for the holiday. A lamb must be purchased for the feast—and not just any lamb but an unblemished one-year-old male. And each home must be cleansed of leavened bread. Everywhere throughout Jerusalem, women frantically sweep floors and wipe down counters because even so much as a single crumb can bring forth impurity. At Lazarus’s home, Martha and Mary are fastidious in their scrubbing and sweeping. After sundown Lazarus will walk through the house with a candle, in a symbolic search for any traces of leavened products. Finding none, it is hoped, he will declare his household ready for Passover.

At the palace home of the high priest Caiaphas, slaves and servants comb the grounds of the enormous estate in search of any barley, wheat, rye, oats, or spelt. They scrub sinks, ovens, and stoves of any trace of leaven. They sterilize pots and pans inside and out by bringing water to a boil in them, then adding a brick to allow that scalding water to flow over the sides. Silverware is being heated to a glow, then placed one at a time into boiling water. There is no need, however, to purchase the sacrificial lamb, as Caiaphas’s family owns the entire Temple lamb concession.

At the former palace of Herod the Great, where Pontius Pilate and his wife, Claudia, once again are enduring Passover, there are no such preparations. The Roman governor begins his day with a shave, for he is clean-shaven and short-haired in the imperial fashion of the day. He cares little for Jewish tradition. He is not interested in the traditional belief that Moses and the Israelites were forced to flee Egypt without giving their bread time to rise, which led to leavened products being forbidden on Passover. For him there is

ientaculum

,

prandium

, and

cena

(breakfast, lunch, and dinner), including plenty of bread, most often leavened with salt (instead of yeast), in the Roman tradition. Back at his palace in Caesarea, Pilate might also be able to enjoy oysters and a slice of roast pork with his evening meal, but no such delicacies exist (or are permitted) within observant Jerusalem—particularly not on the eve of Passover. In fact, Caiaphas and the high priests will even refrain from entering Herod’s palace as the feast draws near, for fear of becoming impure in the presence of the Romans and their pagan ways. This is actually a blessing for Pilate, ensuring him a short holiday from dealing with the Jews and their never-ending problems.

Or so he thinks.

* * *

Judas Iscariot watches Jesus with a quiet intensity, waiting for the Nazarene to reveal his Passover plans so that he can slip away and inform Caiaphas. It would be easy enough to ask the high priest to send Temple guards to the home of Lazarus, but arresting Jesus so far from Jerusalem could be a disaster. Too many pilgrims would see the Nazarene marched back to the city in chains, thus possibly provoking the very riot scenario that so terrifies the religious leaders.

Judas is sure that none of the other disciples knows he has betrayed Jesus. So he bides his time, listening and waiting for that moment when Jesus summons his followers and tells them it is time to walk back into Jerusalem. It seems incomprehensible that Jesus would not return to the Holy City at least one more time during their stay. Perhaps Jesus is waiting for Passover to begin to reveal that he is the Christ. If that is so, then Scripture says this must happen in Jerusalem. Sooner or later, the Nazarene will go back to the Holy City.

* * *

Next to the Temple, in the Antonia Fortress, the enormous citadel where Roman troops are garrisoned, hundreds of soldiers file into the dining hall for their evening meal. These barracks are connected to the Temple at the northwest corner, and most men have stood guard today, walking through the military-only gate and onto the forty-five-foot-wide platform atop the colonnades that line the Temple walls. From there, it is easy enough to look down on the Jewish pilgrims as they fuss over last-minute Passover preparations. The entire week has been demanding and chaotic for the soldiers, who have spent hours standing in the hot sun. But tomorrow will be their most demanding day of all. Lambs and pilgrims will be everywhere, and the stench of drying blood and animal defecation will waft up to them from the innermost Temple courts. The slaughter will go on for hours, as will the sight of men clutching the bloody carcasses of lambs to their chests as they rush from the Temple courts to cook their evening Seder.

Normally, the garrison comprises little more than five hundred soldiers and an equivalent number of support staff. But with Tiberius Caesar’s troops having arrived from Caesarea for Passover, the number of legionaries has swollen into the thousands—and accompanying them is a full complement of support units and personal servants to shoe horses, tend to baggage, and carry water. Thus the dining hall is loud and boisterous as the men sit down to a first course of vegetables flavored with

garum

, the fermented sauce made of fish intestines that is a staple of Roman meals. The second course is porridge, made more flavorful with spices and herbs. Sometimes there is meat, but it’s been hard to procure this week. Bread is the staple of the soldiers’ diet, as is the sour wine made by combining vinegar, sugar, table wine, and grape juice. Like everything else set before these famished men, these are consumed quickly, and in large quantities.

Twelve soldiers hunch over their meals with the knowledge that they will witness the slaughter of much more than sheep tomorrow. For these are the men of the crucifixion death squads, soldiers of impressive strength and utter brutality assigned to the backbreaking task of hanging men on the cross, Roman-style.

Each crucifixion death squad consists of four men known as a

quaternio

. A fifth man, a centurion known as the

exactor mortis

, oversees their actions. Tomorrow three teams of killers will be needed, for three men have been condemned to die. The initial floggings will take place within the Jerusalem city walls, but the hard work of hoisting the men up onto the cross will take place outside, on a hill known as Calvaria or, as the Jews say in Aramaic, Gulgalta—or, as it will go down in history, Golgotha. Each word means the same thing: “skull,” the shape of the low rise that is a place of execution. Even as the

quaternio

gulp down their dinner, the vertical pole onto which each man will be nailed already rests in the ground. These

staticula

remain in position at all times, awaiting the arrival of the

patibulum

, the crossbar that is carried by the condemned.

In truth, a crucifixion can be accomplished with fewer than five men. But Roman standards are high, and it is part of each executioner’s job to keep an eye on his fellow members of the

quaternio

, ensuring that there is no sign of lenience toward the prisoner. A smaller death squad might not be as diligent. So it is that these well-trained soldiers approach tomorrow’s crucifixions with total commitment. Anything less might result in their own punishment.

One of the men they will crucify is a common murderer named Barabbas. The other two are suspected of being his accomplices. In the morning, the death squads will begin the ritual crucifixion process. It is intensely physical work, and by day’s end their uniforms and bodies will be drenched in blood.

East view of the Temple showing the Antonia Fortress

But the soldiers of the death squads don’t mind. In fact, many of them enjoy this work. They are thugs, tough men from Samaria and Caesarea whose job it is to send a message: Rome is all-powerful. Violate its law and you will die a grisly death.

* * *

It is evening as Jesus leads the disciples back to Jerusalem for their final meal together. A benefactor has kindly rented a room for Jesus in the Lower City. It is on the second floor of a building near the Pool of Siloam. A long rectangular table just eighteen inches tall is the centerpiece of the room. It is surrounded by pillows on which Jesus and his disciples can lounge in the traditional fashion as they eat. The room is large enough for all to recline comfortably but small enough so that their overlapping conversations will soon fill the room with high-volume festive sounds.

Jesus sends John and Peter ahead to find the room and assemble the meal.

1

This is most likely a tense time for Judas Iscariot, for he finally knows that Jesus plans to return to Jerusalem, but he does not know the hour or the exact location—and even when he obtains this information, he must still find a way to sneak off and alert Caiaphas.

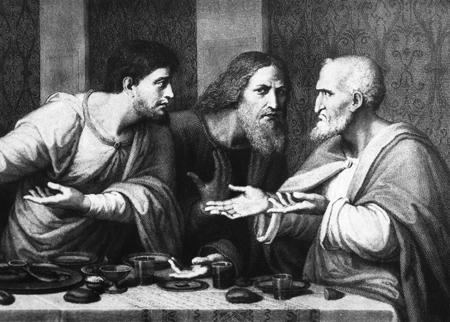

The Last Supper in the Upper Room

Once in the room, Jesus begins the evening by humbling himself and washing each man’s feet with water. This is a task normally reserved for slaves and servants, and certainly not for a venerated teacher of the faith. The disciples are touched by this show of servility and the humility it implies. Jesus knows them and their personalities so well and accepts them without judgment: Simon the zealot, with his passion for politics; the impulsive Peter; James and John, the boisterous “sons of thunder,” as Jesus describes them;

2

the intense and often gloomy Thomas; the upbeat Andrew; the downtrodden Philip; and the rest. Their time together has changed the lives of every man in this room. And as Jesus carefully and lovingly rinses the road dust from their feet, the depth of his affection is clear.

During dinner, Jesus turns all that good feeling into despair. “I tell you the truth,” he says, “one of you will betray me.”

The disciples haven’t been paying close attention to their leader. The meal has been served and they are reclined, chatting with one another as they pick food from the small plates. But now shock and sadness fill the room. The disciples each take mental inventory, search for some sign of doubt or weakness that would cause any of them to hand over Jesus. “Surely, not I, Lord,” they say, one by one. The comment goes around the table.

“It is one of the twelve,” Jesus assures them. “One who dips bread into the bowl with me. The Son of Man will go, just as it is written. But woe to that man who betrays the Son of Man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.”