Kiss and Tell (4 page)

Authors: Shannon Tweed

LANCE SARA KIM AND SHANNON. OUR HOMEMADE DRESSES.

I developed another bad habit when I graduated to the upper grades and started to attend the school near the bigger town of Dildo. I immediately became totally addicted to Cheetos. I hadn’t had much pre-packaged food, and now I was exposed to a cafeteria. I would just toss the food from my lunch box right into the garbage and go straight for the Cheetos, salt-and-vinegar chips, or Sno-balls. It’s my theory that if you give your kids a little they’re not going to crave a lot, but if they never have any, they can’t wait to get their hands on those little wrappers. I went absolutely wild for all that packaged food, and to this day I have a junk food addiction that will not quit. But now I also appreciate the stews, bread, soups, and other homemade things my mother taught me to make.

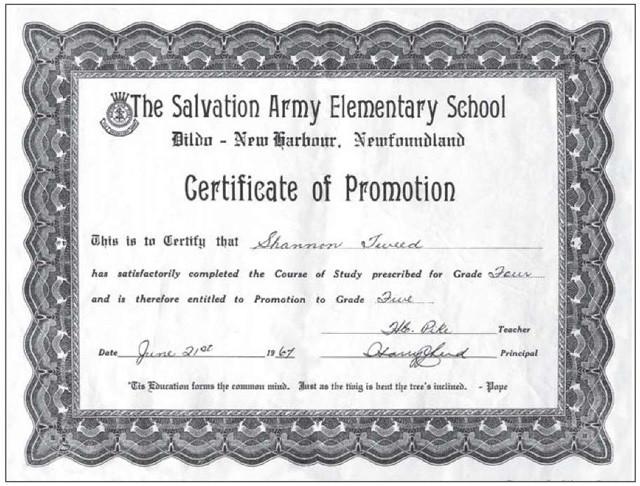

NOTE THE NAME OF THE TOWN ON MY DIPLOMA DILDO?! COULD THIS BE A SIGN OF THINGS TO COME?

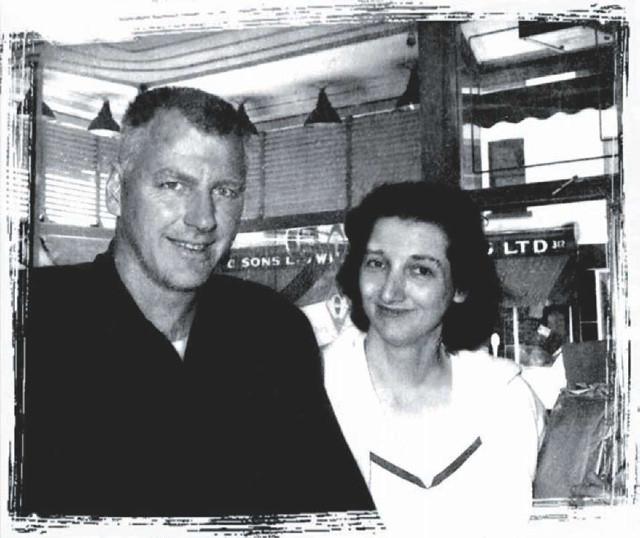

MOM AND DAD’S MOTHER IN THE STORE. IT WAS HERE SHE GATHERED UP GOODIES FOR OUR SPECIAL BIRTHDAY PACKAGES.

My grandfather on my father’s side owned a confectionery, a little store in Saskatchewan, and he used to send a box of goodies on each of the kids’ birthdays. When mom went into town and came home with that brown box it was so exciting. We knew it was full of candy. We knew some of the contents would be crushed from the journey, but there was always plenty of good stuff left, and there were always fights over who got what. I liked the Sweet Marie’s, O’Henry’s, and marshmallow Circus Peanuts. It’s one of my fondest memories now—that battered brown box, all the way from Saskatchewan, thousands of miles away from a grandfather and grandmother I didn’t know.

ANOTHER NIGHT IN PINCURLS; ANOTHER WACK BANG JOB.

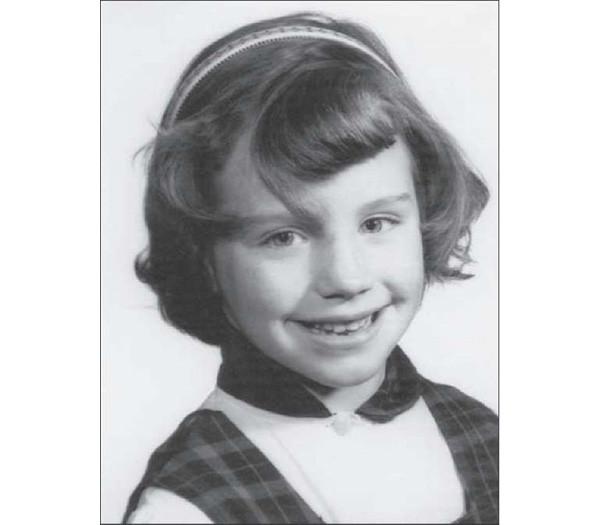

As a little girl I wanted to look like the girls in the Sears catalog, even though I actually looked more like Pippi Longstocking. I always had skinned knees, and there was nobody thinner than me. I had freckles all over my skinny little body, and my hair was an unattractive mixture of red, blonde, and brown. At some point I started sleeping in big brush rollers, the kind that hurt your head, because I thought it was cool, but the curls always turned out very lopsided. School photographs always reflected how little sleep I had gotten the night before and how crooked my freshly cut bangs were. (With seven children, we all took our baths at night; so we all slept on our wet hair, which didn’t make for pretty pictures, anyway.) My mom eventually showed me how to make pin curls, which were a little easier to sleep on but produced the same hideous result.

That Sears catalog—as a young girl, it really fired my imagination. I started studying the girls in its pages, looking through it and telling myself, “I’m going to be in there someday.” I wondered how I could possibly become a model for the Sears catalog; it seemed so glamorous. Those poses—one hand on the hip and one foot pointed out—made the girls look like mannequins. They seemed to me the essence of elegance. I didn’t have any conviction that I was pretty enough to model, but I was reasonably sure I could pose like the girls did. I didn’t get so far in my daydreams as to think about whether somebody would actually hire me or not. It was all a fantasy.

All us kids pored over the pages of the catalog, making wish lists of the clothes we would buy during our twice-a-year trips to town. My wishes rarely ever came true; there were seven kids, after all. My parents did the best they could. Twice a year my mom packed up three, four, or five of us (whoever was old enough to walk) and drove into town. There were two choices for wardrobe: Woolworth’s or Simpson’s (as Sears was then known in Canada). These trips were one of the rare times during the year we ate restaurant food; we would have french fries with gravy and sodas at the Woolworth’s counter, a much-anticipated treat. (To this day I love fries and gravy with vinegar and ketchup!)

The kids who didn’t get hand-me-downs were allowed to pick new clothes, and Mom bought our school uniforms: black lace-up oxfords, white shirts, and, for the girls, little navy pinafore-type dresses. They were dreadful. There were also blazers that we inevitably lost, and, of course, galoshes (we called them rubbers) that went over our shoes to protect them from the muck. The ground was usually very slushy, even though it didn’t get brutally cold in our region of Canada. One of the reasons my parents raised mink was that Newfoundland wasn’t as cold as the rest of Canada, and the summers weren’t as hot. It was a viable place to have rows and rows of sheds that didn’t need heat or air-conditioning, but galoshes were a must.

In retrospect I realize that

town

was only 62 miles away. I drive my own kids practically that far every day now taking them to and from school. But in those days it was a big trip.

Town

was where it was at—a very exciting place. Looking back, I also cannot fathom how my mom did it all. I have a nanny for my two kids, and there still aren’t enough hours in the day. Seven kids—can you imagine? That’s an incredible amount of work just to keep the meals, the clothes, the homework assignments, and the chores straight. The older kids did help, and I was always keeping my eye on one sister or brother so she or he didn’t fall in the pond or run down the driveway to the highway. My older sister Kim had the unenviable task of watching out for all of us, which caused rifts between her and me. “You are not the boss of me!” I used to scream at her, and fights would ensue. I even locked her in the basement once when my parents were out, just for spite.

During the time my dad was building our new house, the government sent workers around to start paving the gravel highway that bordered our land. This was a thrilling event. Our ranch lay at the top of a very long driveway, and we would trek down to the highway to take cookies we’d baked to the workmen. How things have changed. I wouldn’t let my kids near strangers, but back then, and there, we felt safe. Everyone knew everyone else.

It’s a scary world out there now, but when I was a child, out in the country, there was nothing to fear. We thought we didn’t have to worry about things like children being kidnapped or sexual predators then. I used to walk to the store two miles away all by myself or with a sibling, before I was seven years old. (Now, in L.A., I live with locks on the doors, dogs, alarms, security systems— everything.) We felt very safe, or maybe I was just sheltered. We didn’t have television until I got older—at some point we got a black-and-white TV with two grainy channels. There were no horror stories—nothing except the boogeyman just after the lights went out. Then we loved to scare each other, the girls in one room and the boys in another. We spooked the living daylights out of each other before Mom came in to read to us each night.

We had homemade nightgowns and pin curls. I can still recite the Lord’s Prayer.

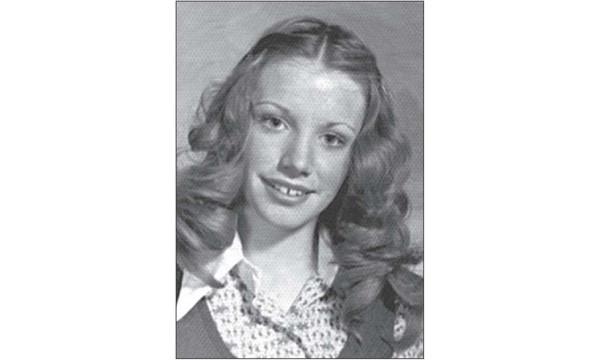

EARLY MODELING PHOTOS.

Chapter Two

Little Girl Lost

I

n October 1966 my world came crashing down and my childhood came to an abrupt end. I was nine years old. I’m sure my life would have been completely different if the accident hadn’t happened. I would probably never have wandered too far from the ranch. I could easily be sitting in Dildo right now with five kids.

A friend of my dad’s bought a brand-new car and drove over to show it off one cold evening. He was anxious to take my dad out for a ride. My dad was really more interested in feeding his horses, but his friend helped him with the chores and persuaded him to come out for a short ride. They wound up at a pub and had a few. While they were relaxing in the pub, snow started to fall, making the roads, which weren’t all that great to begin with, much more dangerous.

Who knows what really happened? Maybe they were busy talking and joking and not paying attention; maybe they hit a patch of ice; or maybe they were really too drunk to drive. Whatever the case, they were certainly speeding, going much too fast on winding, narrow country roads. My dad’s friend completely missed a treacherous right-hand turn on the familiar road home and slammed the car into a huge rock wall. He was thrown out of the car and died instantly.

My dad was hurled through the windshield and into the branches of a tree, where he hung undiscovered for hours. Nearly every bone in his body was broken. It wasn’t until daylight that another car happened along and reported the accident. It initially appeared to be a fatal crash involving only the driver because my dad was nowhere to be seen. The only reason he was found at all was that the rescuers heard a very faint breathing-moaning sound and discovered him tangled up in the tree, barely clinging to life.

Since his injuries were obviously far beyond the scope of the little local hospital where I was born, my dad was taken to the hospital 60 miles away in St. John’s. All of the doctors were sure he was going to die, and they concentrated only on keeping him alive minute by minute. He was in a coma, where he remained for a long time, and was certain to have brain damage. He had 19 fractures and stem cell injury; was hooked up to catheters and monitors; laid out on a refrigeration sheet—everything. It was catastrophic.

The days immediately following the accident were a blur. There was a popular song at the time with the line, “Daddy don’t you walk so fast.” I used to sing that song and cry every night for weeks after my dad’s accident. When I went back to school, the other kids and teachers kept coming up to me and offering condolences, and I didn’t really understand why. Other people who knew more than I did about the accident were patting me on the shoulder and saying, “I’m so sorry about your dad,” as if he was gone already. He was gone, physically, but not dead. A hole in my heart appeared that I would spend many years trying to fill. It was a terrible, frantic feeling. This was about the time we stopped going to church and reciting the Lord’s Prayer each night. I ditched God; where was he when we needed him?

MOM AND DAD IN ST. JOHN’S, NEWFOUNDLAND.

The accident was such a tragedy on every level. Up until the minute it happened, my mom and dad were still crazy about each other; they were always having fun together, whooping it up. Whenever one of us burst into their room in the mornings they’d have to scramble to get decent. He was always smacking her behind when she walked past and grabbing her and kissing her. That was my frame of reference for how a marriage should be. It was what I wanted in a partner. I wanted someone to adore me, and I looked for it forever. But for my mom that ideal husband was no more.

The entire structure of our lives was gone. My parents had been an excellent team in every way. My mom’s job had been to raise the kids, keep house, and do the bookkeeping for the ranch. My dad’s job had been to provide for us and do the manual labor. After the accident, my mom had to take on the physical outdoor work as well as run the whole operation.

Daddy was allowed to come home after several months in the hospital. He emerged from his coma a very angry man. He was not the father I remembered; he had become an entirely different person. He had good reason to be angry: to him, it seemed that he woke up one day and his seven children and ranch were all gone, never to return. He now behaved like a very angry, confused child. He and my mother fought. There was no kissing anymore. No laughter, no hugs, very little hope. If I had been in my mother’s place, I would have killed myself. That was a lot for one woman to bear.

I’m sure my parents had many anguished discussions, with my mom saying things like “I can’t do this alone—the ranch, the business, seven kids—what am I supposed to do now? I have to sell; I have to leave.” My father was dead set against it. It was his ranch, his whole life, and his livelihood that he had worked so hard to build from nothing. I can imagine that fight as an adult, but they were good about sheltering us from all the tension. As a nine-year-old all I knew was we lived on a ranch, Daddy had an accident, and now we were going to have to leave.

My dad was only home for two weeks in a wheelchair before he had to return to the hospital for an extended period of time. It was now clear he would survive, and the doctors had to work on those bones not properly set when they were so sure he would die. He had a very long rehabilitation ahead, including months of strenuous physical therapy.

The brain injuries my father sustained were similar to those of a stroke victim—he had to learn how to walk and talk and drive again. It was fascinating, in a scary way, to see his inability to hide any of his feelings after the accident. I believe that our family life might have been salvaged if he had been able to keep his emotions in check, but my dad could not stop whatever he was thinking or feeling from coming out of his mouth. He no longer had a filter. His personality had irrevocably changed. It was heartbreaking to see my strong, vibrant father turned into this angry, crippled mess in a wheelchair.

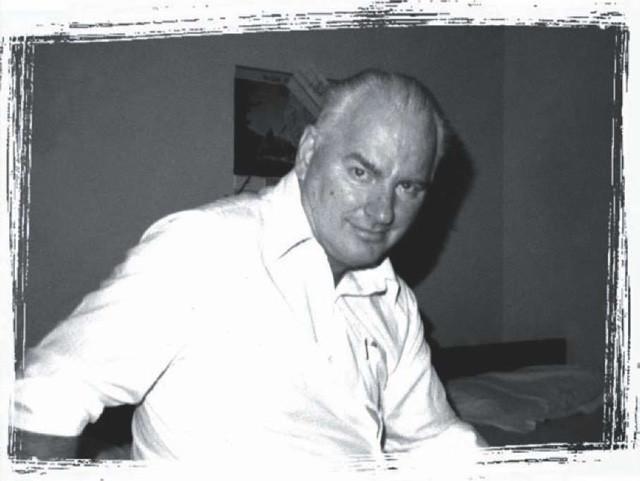

DONALD KEITH TWEED. PORTRAIT OF A BROKEN MAN: DAD AFTER THE ACCIDENT ON A VISITATION DAY.

All these abrupt changes were devastating to me and, I’m sure, to my siblings. I was the only family member my dad would tolerate coming near him when he came home for his visit in between operations and rehabilitation, and he needed a lot of help. He wouldn’t allow anyone else to take him to the bathroom or help him walk. He was so heavy. I remember him leaning on Mom and me—he clung to me, and I couldn’t understand why. I was just an ordinary little girl, one whose daddy was now gone—there physically, but his essence was gone forever. However, there was something about me he liked and things about some of the other kids he now hated and verbalized. The outbursts were due to the brain trauma, but it was incredibly hurtful, especially to my brothers, to have their father not like them anymore and say cruel things to them. My brothers were careful to never get too close. The whole thing was bizarre and emotionally upsetting. I knew he didn’t really mean his harsh words, but it made me cry all the time—for them, for him, and for all of us.

For a while after my dad’s accident, my mother, friends, and the ranch hands managed, but it was the sixties in rural Canada, and the banks took a dim view of a woman’s ability to run a ranch and refused to lend her enough money to keep things going. Nor did my mother’s parents offer any real financial help. They were prosperous motel owners, but I believe there was a bit of bad blood in the family history—some bitterness left over from years before, when my mom had left Saskatchewan as a young woman and gone off with my father to some godforsaken place to raise mink. There was nothing left to do but sell the ranch.

During all this, of course, I still had to go to school every day and carry on, as much as possible, with my regular routine. I developed a very intense crush on my fifth-grade female teacher. I can’t remember her name, but I can still see her so clearly: she was young, with dark hair and brown eyes, and she had a petite little frame. My teacher treated all of her students with loving attention and was so kind that I always wanted to be near her.

As fifth grade turned to sixth, my affections soon turned to one of my friend’s older brothers. Billy played the bass for a local band and was just dreamy-looking. He had dark hair, brown eyes, and some color in his skin. He was dark Irish. His skin was beautiful—unlike mine. (My whole life I’ve had skin problems. I’ve always been the girl with the pimple. I had very oily skin, and my mom promised I would stop breaking out when I got older. Well, I’m almost 50 now, and I’m ready for it to stop, but it hasn’t.) Billy was different from me, and I liked different in a boy. I like opposite.

THIS SCHOOL PHOTO HIGHLIGHTED THE GAP BETWEEN MY TWO FRONT TEETH NICELY, DON’T YOU THINK? ONCE AGAIN, MOM MADE MY OUTFIT.

I am sure my father’s accident played a large part in why I was so desperate for this boy to like me—though maybe it was just hormones, or both. I dreamed of him taking me to the local drive-in or to the soda shop—anything, but whenever I was around, Billy would walk right by me like I wasn’t there.

The first time I was allowed to go to a local teen dance I walked with my older brother and sister the two miles to town. The dance was being held in the Whitbourne billiard hall. I must have been the biggest geek. I remember standing there and just staring at Billy during the dance while he played bass with his band. I’m sure he saw me fixated on him and just thought,

Oh God, get her out of here.

He was much older, 16. Halfway through the dance I had to go home; I had an 11-year-old’s curfew. Just to get rid of me, I’m sure, Billy took me outside for a walk. He kissed me on the forehead and said good-bye. It was a brush-off, but I was on cloud nine. He had kissed me! On the forehead! I was so excited, I thought about that kiss every day for an entire year. But I never saw him again after the dance, because soon after that we moved away.

My parents’ marriage was effectively over. With no help forthcoming from anyone, my mom had no choice but to sell the ranch. It was decided that we were moving to Saskatchewan without my father, where my mother’s sister had a home and family. The three oldest children would be sent ahead to live with my aunt and uncle for a few months, while my mom shut down the whole operation and joined us later with the four younger kids.

The first to leave were Kim, Lance, and me. I left behind my two best friends, Diane and Betty Russell, cousins who had been my girlfriends all through elementary school. Diane and I were closer friends, and she, too, was my opposite—dark hair, brown eyes, olive skin—the friend I had always thought was so beautiful. Once we moved from the ranch, everything was in such turmoil. It never even occurred to me to write letters to my friends or try to stay in touch. It was a clean break; once we got to Saskatchewan we all started over. New school; new home. Not ours, but new.