Kokoda (33 page)

1 August, Saturday. Overcast, occasionally fine.

Last night when the soldiers were chatting together I heard them say that Lt Ogawa, Yukio, Commander of no.1 Company, had been killed in action. I told them with a smile, not to spread rumours but this morning, when I was walking on the North Side of the command group who were reading out the Imperial Rescript, 2nd Lt Hamaguchi confirmed that Lt Ogawa had been killed.

Being very surprised I hurried to the office and looking at the report found that in the Kokoda area our advance force who have been engaged in battle… had suffered unexpectedly heavy casualties.

123

At least the survivors of B Company managed to get a message through to Port Moresby on the morning of 29 July:

‘

Kokoda lost from this morning. Blow the [aero-]drome and road east of Oivi. Owen mortally wounded and captured. Templeton missing.’

124

Fortunately for the Australians there was no immediate compulsion on the part of the enemy to pursue them down the track. Though the Japanese were slightly behind schedule at this point, and the Australians had provided far more resistance than had been expected, the key thing was that the objective of securing Kokoda had now been accomplished. It was now time to make a decision about whether to push on or not.

Communications between Rabaul and Tokyo had flown back and forth, exchanging information and views, but on the morning of 28 July, General Haruyoshi Hyakutake, the Commander of the 17th Army in Rabaul, received the coded cable from Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo he’d been waiting for, and he in turn passed the orders on to Colonel Yokoyama in New Guinea. They had been given clearance to proceed to Port Moresby, which they estimated could be achieved in just eight days march from Kokoda, including fighting.

In Rabaul, General Horii would organise for more men and more supplies to be landed at the Buna beachhead, and push on down the track, which was now being widened and improved by the native labourers brought from Rabaul.

Back in Brisbane on that same afternoon, a key new American general had been welcomed by General MacArthur’s staff. General Thomas Kenney was to take over MacArthur’s air wing, and in the course of his welcome Major General Richard K. Sutherland thought it best to lay on the line just what kind of a situation the Bataan Gang were dealing with. He thought it important that the new general know that the Australians fighting up in New Guinea were ‘undisciplined, untrained, over-advertised and useless’.

125

At least this low opinion of the 39th Battalion served for one thing. With the fall of Kokoda, it was more than ever clear that Port Moresby really was at risk if this southern thrust by the Japanese was not thwarted. So, finally, the wheels were set in motion for the Australian 7th Division who’d earnt their spurs in the Middle East, to get to New Guinea immediately. It had taken a great deal of time, but at last, on 3 August 1942, the orders were given for the 7th Division to move. Within hours, the likes of Stan and Butch Bisset and Alan Haddy and all the soldiers from the 2/14th and 2/16th were packing up their kitbags and making ready.

Still, everything wasn’t as smooth as it might have been. When the time came to embark on the awaiting ships, although their destination was nominally still top secret—though some in the ranks had been told they were heading to a new base in North Queensland— it was clearly not a secret to all. For there on the dock at Townsville were their munitions in huge wooden boxes about to be loaded into the hull of the ship and each clearly marked ‘King’s Harbour Master, Port Moresby’.

126

Against that, was the good news that the munitions were even being loaded at all as the wharfies had recently gone on strike and been successful in their insistence that they receive danger money for handling them!

Stan was just heading up the gangplank to go into the 2/14th’s ship, the

James Fenimore

, when the man just a little way ahead of him suddenly pulled out of the queue. It was Captain Phil Rhoden, the Second-in-Command of the 2/14th and a great friend of Stan and Butch’s from their days with the Powerhouse Club back in Melbourne, where Rhoden had been a strapping sportsman in his own right and also Second-in-Command of the Powerhouse Militia Battalion. Now though, he had just grabbed a wharfie and was speaking to him with some urgency. Be blowed if, in the hurly-burly of departure, Phil hadn’t nearly forgotten the most important thing of all!

‘Mate,’ the army captain said to the wharfie, ‘would you mind posting this for me?’

‘No worries, mate,’ the wharfie replied, tucking the envelope into a greasy pocket, clearly with no idea of just how important it was to the Australian officer. For in the letter Phil Rhoden had poured his heart out to his girlfriend in Melbourne, Pat Hamilton, telling how much the events of the previous two years had made him realise the depth of his love for her and… would she marry him? Captain Rhoden’s task achieved, he hoped, he got back in the line and, together with the Bisset boys and all the rest, not long afterwards the ship departed.

North.

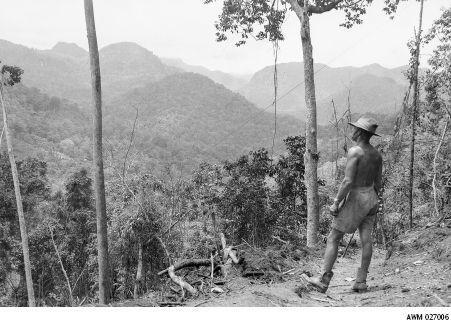

North, way north, as the numbers of Australian soldiers on the Kokoda Track increased—and the loss of the Kokoda airfield meant that nothing more could be flown in—the problem of supply became excruciating. Bert Kienzle and his porters did the best they could, but the situation lurched from one crisis to the next. If the men weren’t desperate for more munitions, it was that the food supply had dwindled to nearly nothing. If it wasn’t medical supplies which had run out, it was blankets.

In desperation, the army had tried what became known as ‘biscuit bombing’, which was low-flying aircraft dropping supplies in crates, or packed tightly inside bags, right beside assembled troops; but that had many problems. One of the main ones was that in the endless green acres of the highlands it was hard for pilots to find the designated drop sites. Another was that when they

did

find the site, it was no easy task to get the crates on target, and even then the crates frequently burst on contact with the ground, while others careened into the jungle where they could never be found. Time and again bags of rice, particularly, hit the ground and burst in the manner of mini-bombs, with the individual grains of rice-shrapnel being spread out over an area as large as fifty square yards. Other bags and boxes disappeared so far into undergrowth that they were simply impossible to find. Biscuits in tins were smashed into crumbs from the impact and tins of bully beef were punctured, meaning their certain ruination in a matter of hours. Some heavy weaponry was dropped and disappeared so deeply into the mud it couldn’t be retrieved. A rough estimation was that sixty per cent of what was dropped was not recovered—at least not by the Australian soldiers, for yet one more problem was when precious supplies fell into the hands of the Japanese…

Finally though, something twigged with Bert Kienzle. Just vaguely, he remembered that on one of his many flights from Kokoda to Port Moresby he had deviated from the most direct route and noted that rarest of all things in the New Guinea highlands—a valley with a fairly large flat piece of ground at the bottom, somewhere between Efogi and Eora. The fact that the area didn’t show up on any maps was perfect as it meant that the Japanese wouldn’t know anything about it. Kienzle left the porter lines in the hands of his offsiders and, taking his two most trusted natives with him, plunged into the jungle at a point where the track crossed a river. Two terribly difficult days later, at last… bingo! There it lay, in the valley below. Exactly the flat area he needed. When Kienzle started down for a closer inspection, however, his porters jacked up.

‘PLES E TAMBU. MEPELA E NOKEN GO LONG DISPELA PLES.’ ‘This place is taboo, and we ain’t going there, sport.’

Kienzle, though, insisted. ‘YU MUS I GO. MI BIKMAN. MI TOK. YU HURIM. MIPELA MUS GO NUW.’ ‘You must go. I am the bigman boss, and when I talk, you hear and obey. We’re going. Get going!’

Reluctantly they accompanied him, and together they were soon at the bottom of an ancient volcano and able to establish that as a drop zone it was perfect. For not only would the place be easy enough to find from the air, but the relatively flat and open terrain— with rough contours of 2000 yards by 600 yards, positioned at an altitude of 6000 feet above sea level—would indeed permit fairly easy recovery in an area close enough to the battlelines that the porters would be spared a week’s walk.

On the spot Kienzle christened the place ‘Myola’ after the wife of his Company Commander at ANGAU, Major Syd Elliott-Smith—the word meant ‘dawn’—and formed up plans to make it the major supply depot for all the subsequent Australian fighting in the area. On the morning of 4 August, he and his porters set off from Myola, blazing a new track along a ridge in a northeasterly direction, to force as direct a route as possible through to the main track leading to Kokoda. The new junction that was formed, thus, was at a flat spot where the track crossed Eora Creek, and Kienzle named it Templeton’s Crossing, in honour of Sam Templeton who, it was now accepted, was not coming back. The main thing was, the job was done. The Australians now had a place to establish an advance supply depot until such times as they re-conquered the Kokoda airfield, which would make everything easier still.

And on that subject, there were already plans afoot…

In the first days of August 1942, the battle-wearied veterans of the 39th who had seen action at Awala, Wairopi, Gorari and Kokoda were joined by the rest of the exhausted 39th Battalion who had made their way forward to the picturesque village of Deniki, which overlooked the Yodda Valley leading to Kokoda. Together as a battalion for the first time in the highlands, there were some 460 members gathered. Together with the remnants of the Papuan Infantry Battalion, and a few soldiers from the ANGAU force and some native policemen, Maroubra Force now numbered five hundred. The ‘veterans’—for that is what they now were—were pleased to see the new arrivals for more reason than that they were friends and reinforcements. Far more urgently they had some

food

, which the veterans lacked. Though it was putting it too high to say that those who had been on the track for the last month were outright starving, the fact was that their supplies were pitifully low. Fortunately the new fellas had no hesitation in sharing what few rations they had left after their own long trek. As they shared the food, and the stories, the spirit of the men seemed to lift. This wasn’t like being a lost battalion in the backblocks of Port Moresby counting the hours of every stinking day till it was done and they were closer to home. This was like being a full body of fighting men together for the first time on the battlefront up against a ruthless enemy, and aware that from here on in they would be depending on each other.

The fresh arrivals—though fresh was hardly the word for them, given their six-day trek to get there—included Major Alan Cameron, who walked into Deniki on 4 August to take provisional command of the 39th after the death of the valiant Colonel Owen. Major Cameron was a no-nonsense military officer complete with bushy moustache and fired up by what he had witnessed in the fall of Rabaul in much the same manner as Colonel Owen had been. He had served with the 2/22nd Battalion there, and also witnessed the Japanese barbarity, before managing to flee in an open boat with twelve others. Very much of the ‘take-charge-and-then-chaaarge!’ school of military thinking—as he had first learned with the cadets at Melbourne’s elite Scotch College—Major Cameron was frank in his first meeting with the 39th’s officers, where he laid it on the line.

First up, he was not well pleased with the performance of the 39th thus far. With very little idea of what had gone on to this point, and seemingly no cognisance of the fact that these wet-behind-the-ears young men from Victoria had taken on hardened Japanese veterans and acquitted themselves well, Major Cameron was brutal. He focused on his view that there had been some Australian soldiers from B Company who had shot through in the thick of defending Kokoda, some of whom he had been appalled to meet on the track as he was walking to get to the front. And he was also appalled that as a company they had continued to fall back in the face of the Japanese. Put together, it meant that the name of the 39th was forever sullied. His comments did not sit well with his exhausted but now outraged officers, who, despite everything, knew that the men had bloody well done

all right

and for that matter weren’t aware of anyone who had shot through. As for falling back, they knew there had been no choice if they were to live to fight another day. But they continued to listen as Cameron told them what the men of the 39th were going to do now to redeem themselves.