Kokoda (4 page)

At another ‘coalface’ of action—St John’s Catholic Church debutante ball—young Joe Dawson was making an impression on young Elaine Colbran. And she on him…

Although he’d known Elaine since they were at primary school together Joe had never thought about her in a particularly romantic way, but there was no denying that the red-haired Elaine had turned into a singularly pretty young woman. And she was kind. And she was fun.

As to the young men of Shikoku, they too had changed. For in the image of the country around them, they had grown, developed new muscles and were increasingly eager to test them out. The fact that Japan had grown both in industrial and military might year by year now meant that all able-bodied young boys went into the universal service of the Imperial Japanese Army and underwent intense training. As soldiers in Japan, they were thus heirs to the tradition of the samurais, the uniquely Japanese warrior class which for so many centuries had been regarded as embodying the nation’s highest virtues.

While the samurais of old, however, had lived a life with a rigid code of ritualised behaviour and highly refined sense of honour and ethics known as

Bushido

, what was left to these young men in the 1930s was not quite that…

They were proceeding through far and away the most brutal army training system in the world, where beatings from non-commissioned officers were part of the daily fare, and not simply for individual transgressions. It was enough that a member of your platoon had committed even a minor infraction that the whole corps was beaten by superiors, some to the point of unconsciousness. The focus was always discipline, absolute discipline, the need to obey orders instantly without question, whatsoever those orders might be. Individual initiative was not only left unrewarded, it was severely punished both physically and by public humiliation in front of your peers.

One aspect of the samurai tradition that survived intact was that the recruits were taught that they must be willing to give their lives in the service of the Emperor. Each morning, at the first lustre of the pre-dawn, each recruit rose, bowed respectfully in the direction of Tokyo’s Imperial Palace, and repeated the famous declaration of the Emperor Meiji: ‘Duty is weightier than a mountain, while death is lighter than a feather.’ This did

not

mean that those soldiers were to throw their lives away, merely that the principal weapon they possessed as a body of fighting men was that death must hold no fear for them.

While they had been taught this idea from infancy, it was now beaten in: death on the battlefield was a beginning, not an end. Death on the battlefield transformed one into a type of god, a ‘Kami’, who remained among the living with the ability to nurture and protect loved ones from that spirit world. And for that transformation, one would be honoured by all, revered forever by ensuing generations for their sacrifice for the good of the nation and the Emperor.

It was nothing if not intense, and it created an extremely tightly bound military machine of formidable capacity. The bonds between these Japanese soldiers were all the greater because many had known each other from early childhood onwards. This, too, was a part of the carefully constructed Japanese military system, the reckoning being that because soldiers’ families were known to each other, no soldier would visit disgrace and dishonour on his loved ones by deserting during a battle.

All,

all

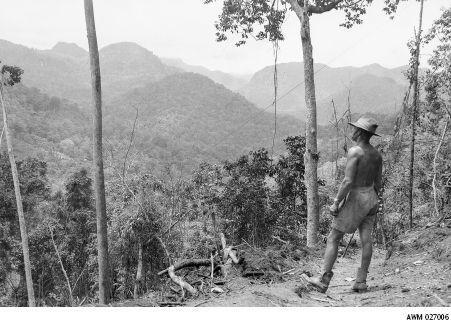

had changed, except Papua New Guinea.

The island still just sat there—immovable, a dark green, impenetrable silhouette, perched above the Australian continent exactly as it always had been. If, at any time in its past, an open calendar had been tacked to a tree in the New Guinea highlands, it would

not

have fluttered over page after page as the years rushed by, the way it often did in the new genre of ‘movies’ which by the 1930s were taking a faraway place called ‘Hollywood’ by storm. For although time

did

pass in New Guinea it didn’t actually change anything substantial from one wet season to the next…

Various powers and forces, from Germany, to Great Britain, to Christian missionaries to the twentieth century had done their level best to gain a foothold on the island—and just managed to do so— but never succeeded in doing anything more than that. Always, it was a place where so much energy was expended just holding on to the one foothold, that trying to find a spot to put down the next foot was all but out of the question.

Even for such a timeless place as New Guinea, though, a force was building that would cause an event so cataclysmic that nothing, absolutely nothing, would be left unchanged by it…

On 26 February 1936, extreme militarists in Japan, in the form of a group of ambitious army officers, shot two of Emperor Hirohito’s key advisers, before other militarists of the same bent, seized key Tokyo installations, including the Japanese Foreign Office. They then handed out leaflets which were a veritable call to arms for Japan’s citizens to rise up with them and recognise that the essence of Japan was rooted ‘in the fact that the nation is destined to expand’, and that those who did not embrace that concept were guilty of ‘treason’. Though that attempted coup failed, the notion that expansion by military means was Japan’s destiny did not.

In July of the following year the Imperial Japanese Army, which four years earlier had occupied the resource-rich Manchuria in neighbouring China, went after the rest of the country, including Peking. Still, Chinese resistance continued to be strong, nowhere more so than in the city of Nanking, the capital of the Nationalist Chinese. When finally the Chinese soldiers defending Nanking surrendered, the Japanese soldiers showed no mercy. Many thousands of the Chinese were put up against the wall and cut down by machine-gun fire, while hundreds were used for bloody bayonet practice and unceremoniously thrown into the Yangtze River. Still, the Japanese were not done. For weeks afterwards the victorious soldiers looted the city, destroying more than a third of its buildings, while murdering many of the city residents and raping, almost as a military policy, some twenty thousand women. Dreadful stories emerged of Japanese soldiers forcing fathers at gunpoint to rape their own daughters, and sons to rape their mothers. Many civilians weren’t simply shot, but were disembowelled and decapitated by soldiers who seemed insane with bloodlust.

This riot of death and destruction reached its apocalyptic apogee when at the city quay, before assembled foreign correspondents, Japanese soldiers began butchering Chinese prisoners of war almost as part of a show, happily posing for photographs with the slain at their feet. The whole episode became known as the ‘Nanking Massacre’ or the ‘Rape of Nanking’ and, given the delight the Japanese had in demonstrating their brutality to foreign correspondents, its news spread far and wide. Later calculations established that somewhere between 100 000 and 300 000 Chinese had been killed.

In response to events such as the Nanking Massacre, the United States of America was quick to impose economic sanctions on Japan until such times as it withdrew from China. Henceforth, the United States government, led by an enraged President Roosevelt, began to limit exports of oil and scrap iron to Japan.

The same approach was not taken by the ruling political class in Australia, though there was no doubt which way the sympathies of the workers lay, setting the scene for a major political brawl which occurred in November of 1938.

Down at Port Kembla, just south of Sydney, the waterside workers refused to load a cargo of pig-iron into a ship bound for Japan on the grounds that they thought that it would likely end up in bullets and bombs that the now supremely militaristic nation of Japan were then firing and hurling at China in a notably vicious war. The workers further argued that once Japan had finished with China, it was quite possible that Australia might find itself on the receiving end of this same pig-iron.

In reply, the Australian government, most particularly Attorney-General Robert Menzies, took a heavy hand. For Menzies the issue was simple: it was

not

for the wretched trade unions to determine Australian foreign policy, and the government would sooner close down the steelworks on which the workers depended for their employment than cede to them any say whatsoever.

So the steelworks were indeed shut down, and after a bitter campaign which included new legislation being passed which forced the workers to cooperate or lose their jobs in the whole industry, Menzies won the day. Just before Menzies became Prime Minister of Australia on 26 April 1939, the pig-iron went to Japan, and Menzies had found a nickname that would stay with him for life: ‘Pig-Iron Bob’.

Growing alarm in Australia about Japanese intent in the region, coupled with an equal alarm about Hitler’s new designs on the map of Europe ensured that all over Australia men began to join up with their local militias or, as they were formally known, Citizens Military Forces, a kind of antechamber for the army proper.

Down in Melbourne, for example, no fewer than 250 members of the Powerhouse Club—including Stan and Butch Bisset—joined up to form C Company of the 14th Militia Battalion, based at Prahran, and proudly became ‘Weekend Warriors’. A couple of times a week, often just before rugby training, or perhaps on the morning before the game, they would form up at a spot close to their clubhouse at Albert Park Lake and practise basic military skills like marching, saluting and shooting at the miniature rifle range they had built. Butch Bisset was always the stand-out performer in the last endeavour, taking on all-comers and always winning. The blokes reckoned that if he wanted to, Butch could wing a flying sparrow at a distance of a hundred yards. For every twenty shots, Butch would get at least nineteen bullseyes.

The men also learnt how to use a gas mask, what the basic military regulations were and what happened if you disobeyed them. Some of the more interesting stuff was when they were given battle formations with miniature soldiers on model terrains, and were asked to work out how to manoeuvre the soldiers to maximise damage to the enemy. Very occasionally they’d go out and practise actual war games against other militia battalions to see who could adapt the quickest and move most effectively.

There is something stirring in the vision of men on horseback charging forward that stiffens the sinews, stirs the blood and awakens an atavistic spirit long dormant. Out on the sandhills of Cronulla in southern Sydney on this summer’s day of 1938, the great Australian film-maker Charles Chauvel and his production crew were thrilled as they captured scenes for Chauvel’s film

Forty Thousand Horsemen,

based on the famous charge of the Australian Light Horse Regiment in the Great War, where they had covered themselves in glory at the Battle of Beersheba. Amid the thundering hooves the only real worry for the delighted Chauvel and his staff was for one of the cameramen, a Damien Parer, who seemed to be taking extraordinary risks jumping around amidst the galloping nags, taking footage from ground level.

5

This fellow Parer did, admittedly, provide extraordinary vision, but the

risks

he took! Just one veering horse at full tilt and that would have been the end of him.

For Damien Parer this episode was simply one step on the way of a busy life pursuing his passion of capturing reality in a box, both through still and moving photography. Such was his overall talent, that in short order, by the end of 1938, he had gone to work for the leading still photographer of his day, Max Dupain, working out of his Kings Cross studio, learning ever more about how to frame a shot for maximum effect, the kind of light that was most effective, the level of exposure and so on…

A lot of what Parer learnt there he found useful for his cinematography craft as well, though what interested him more and more at the time was not the Chauvel re-creation of something that had occurred a long time before, but something even more powerful. What he loved was the idea of capturing important events, live as they actually happened, and then cutting them together exactly as you would for a fictional film, in such a way that the event

lived

.

Meanwhile, far from Australia, the 1939 Wallabies Test team had just disembarked from the P&O liner

Mooltan

on the first leg of their ten-month, five-test rugby union tour. The eight-week trip had been a long haul for Stan Bisset and the team and they were excited and bursting with the energy of the newly landed. The team had just settled into the Grand Hotel on the esplanade of the picturesque British seaside resort of Torquay on this Sunday morning, 3 September 1939, when the word went around that the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, was about to make some kind of national address and they should turn their radios on in their rooms.

‘I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street,’ he began in his clipped, but still rather unsteady tones. ‘This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that unless we heard from them by 11.00 a.m. that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany…