Kull: Exile of Atlantis (19 page)

Read Kull: Exile of Atlantis Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

Kull snarled in defiance.

“I sought not your cursed kingdom. I seek Brule the Spear-slayer whom you dragged down.”

“You lie,” the lake-man answered. “No man has dared this lake for over a hundred years. You come seeking treasure or to ravish and slay like all your bloody-handed kind. You die!”

And Kull felt the whisperings of magic charms about him; they filled the air and took physical form, floating in the shimmering light like wispy spider-webs, clutching at him with vague tentacles. But Kull swore impatiently and swept them aside and out of existence with his bare hand. For against the fierce elemental logic of the savage, the magic of decadency had no force.

“You are young and strong,” said the lake-king. “The rot of civilization has not yet entered your soul and our charms may not harm you, because you do not understand them. Then we must try other things.”

And the lake-beings about him drew daggers and moved upon Kull. Then the king laughed and set his back against a column, gripping his sword hilt until the muscles stood out on his right arm in great ridges.

“This is a game I understand, ghosts,” he laughed.

They halted.

“Seek not to evade your doom,” said the king of the lake, “for we are immortal and may not be slain by mortal arms.”

“You lie, now,” answered Kull with the craft of the barbarian, “for by your own words you feared the death my kind brought among you. You may live forever but steel can slay you. Take thought among yourselves. You are soft and weak and unskilled in arms; you bear your blades unfamiliarly. I was born and bred to slaying. You will slay me for there are thousands of you and I but one, yet your charms have failed and many of you shall die before I fall. I will slaughter you by the scores and the hundreds. Take thought, men of the lake, is my slaying worth the lives it will cost you?”

For Kull knew that beings who slay may be slain by steel and he was unafraid. A figure of threat and doom, bloody and terrible he loomed above them.

“Aye, consider,” he repeated. “Is it better that you should bring Brule to me and let us go, or that my corpse shall lie amid sword-torn heaps of your dead when the battle-shout is silent? Nay, there be Picts and Lemurians among my mercenaries who will follow my trail even into the Forbidden Lake and will drench the Enchanted Land with your gore if I die here. For they have their own tambus and they reck not of the tambus of the civilized races nor care they what may happen to Valusia but think only of me who am of barbarian blood like themselves.”

“The old world reels down the road to ruin and forgetfulness,” brooded the lake-king, “and we that were all powerful in by-gone days must brook to be bearded in our own kingdom by an arrogant savage. Swear that you will never set foot in Forbidden Lake again, and that you will never let the tambu be broken by others and you shall go free.”

“First bring the Spear-slayer to me.”

“No such man has ever come to this lake.”

“Nay? The cat Saremes told me–”

“Saremes? Aye, we knew her of old when she came swimming down through the green waters and abode for some centuries in the courts of the Enchanted Land; the wisdom of the ages is hers but I knew not that she spoke the speech of earthly men. Still, there is no such man here and I swear–”

“Swear not by gods or devils,” Kull broke in. “Give your word as a true man.”

“I give it,” said the lake-king and Kull believed for there was a majesty and a bearing about the being which made Kull feel strangely small and rude.

“And I,” said Kull, “give you my word–which has never been broken–that no man shall break the tambu or molest you in any way again.”

The lake-king replied with a stately inclination of his lordly head and a gesture of his hand.

“And I believe you, for you are different from any earthly man I ever knew. You are a real king and what is greater, a true man.”

Kull thanked him and sheathed his sword, turning toward the steps.

“Know ye how to gain the outer world, king of Valusia?”

“As to that,” answered Kull, “if I swim long enough I suppose I shall find the way. I know that the serpent brought me clear through at least one island and possibly many and that we swam in a cave for a long time.”

“You are bold,” said the lake-king, “but you might swim forever in the dark.”

He raised his hands and a behemoth swam to the foot of the steps.

“A grim steed,” said the lake-king, “but he will bear you safe to the very shore of the upper lake.”

“A moment,” said Kull. “Am I at present beneath an island or the mainland, or is this land in truth beneath the lake floor?”

“You are at the center of the universe as you are always. Time, place and space are illusions, having no existence save in the mind of man which must set limits and bounds in order to understand. There is only the underlying reality, of which all appearances are but outward manifestations, just as the upper lake is fed by the waters of this real one. Go now, king, for you are a true man even though you be the first wave of the rising tide of savagery which shall overwhelm the world ere it recedes.”

Kull listened respectfully, understanding little but realizing that this was high magic. He struck hands with the lake-king, shuddering a little at the feel of that which was flesh but not human flesh; then he looked once more at the great black buildings rearing silently and the murmuring moth-like forms among them, and he looked out over the shiny jet surface of the waters with the waves of black light crawling like spiders across it. And he turned and went down the stair to the water’s edge and sprang on the back of the behemoth.

Eons followed, of dark caves and rushing waters and the whisper of gigantic unseen monsters; sometimes above and sometimes below the surface, the behemoth bore the king and finally the fire-moss leaped up and they swept up through the blue of the burning water and Kull waded to land.

Kull’s stallion stood patiently where the king had left him and the moon was just rising over the lake, whereat Kull swore amazedly.

“A scant hour ago, by Valka, I dismounted here! I had thought that many hours and possibly days had passed since then.”

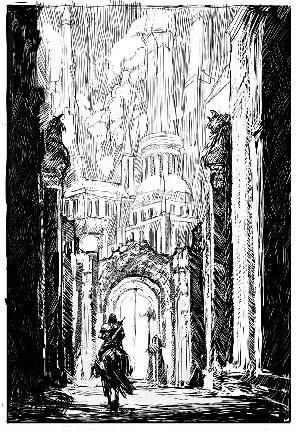

He mounted and rode toward the city of Valusia, reflecting that there might have been some meaning in the lake-king’s remarks about the illusion of time.

Kull was weary, angry and bewildered. The journey through the lake had cleansed him of the blood, but the motion of riding started the gash in his thigh to bleeding again, moreover the leg was stiff and irked him somewhat. Still, the main question that presented itself was that Saremes had lied to him and either through ignorance or through malicious forethought had come near to sending him to his death. For what reason?

Kull cursed, reflecting what Tu would say and the chancellor’s triumph. Still, even a talking cat might be innocently wrong but hereafter Kull determined to lay no weight to the words of such.

Kull rode into the silent silvery streets of the ancient city and the guard at the gate gaped at his appearance but wisely refrained from questioning.

He found the palace in an uproar. Swearing he stalked to his council chamber and thence to the chamber of the cat Saremes. The cat was there, curled imperturbably on her cushion, and grouped about the chamber, each striving to talk down the others, were Tu and the chief councillors. The slave Kuthulos was nowhere to be seen.

Kull was greeted by a wild acclamation of shouts and questions but he strode straight to Saremes’ cushion and glared at her.

“Saremes,” said the king, “you lied to me!”

The cat stared at him coldly, yawned and made no reply. Kull stood, nonplused and Tu seized his arm.

“Kull, where in Valka’s name have you been? Whence this blood?”

Kull jerked loose irritably.

“Leave be,” he snarled. “This cat sent me on a fool’s errand–where is Brule?”

“Kull!”

The king whirled and saw Brule stride through the door, his scanty garments stained by the dust of hard riding. The bronze features of the Pict were immobile but his dark eyes gleamed with relief.

“Name of seven devils!” said the warrior testily, to hide this emotion. “My riders have combed the hills and the forest for you–where have you been?”

“Searching the waters of Forbidden Lake for your worthless carcase,” answered Kull with grim enjoyment of the Pict’s perturbation.

“Forbidden Lake!” Brule exclaimed with the freedom of the savage. “Are you in your dotage? What would I be doing there? I accompanied Ka-nu yesterday to the Zarfhaanan border and returned to hear Tu ordering out all the army to search for you. My men have since then ridden in every direction except the Forbidden Lake where we never thought of going.”

“Saremes lied to me–” Kull began.

But he was drowned out by a chatter of scolding voices, the main theme being that a king should never ride off so unceremoniously, leaving the kingdom to take care of itself.

“Silence!” roared Kull, lifting his arms, his eyes blazing dangerously. “Valka and Hotath! Am I an urchin to be rated for truancy? Tu, tell me what has occurred.”

In the sudden silence which followed this royal outburst, Tu began:

“My lord, we have been duped from the beginning. This cat is, as I have maintained, a delusion and a dangerous fraud.”

“Yet–”

“My lord, have you never heard of men who could hurl their voice to a distance, making it appear that another spoke, or that invisible voices sounded?”

Kull flushed. “Aye, by Valka! Fool that I should have forgotten! An old wizard of Lemuria had that gift. Yet who spoke–”

“Kuthulos!” exclaimed Tu. “Fool am I not to have remembered Kuthulos, a slave, aye, but the greatest scholar and the wisest man in all the Seven Empires. Slave of that she-fiend Delcardes who even now writhes on the rack!”

Kull gave a sharp exclamation.

“Aye!” said Tu grimly. “When I entered and found that you had ridden away, none knew where, I suspected treachery and I sat me down and thought hard. And I remembered Kuthulos and his art of voice-throwing and of how the false cat had told you small things but never great prophecies, giving false arguments for reason of refraining.

“So I knew that Delcardes had sent you this cat and Kuthulos to befool you and gain your confidence and finally send you to your doom. So I sent for Delcardes and ordered her put to the torture so that she might confess all. She planned cunningly. Aye, Saremes must have her slave Kuthulos with her all the time–while he talked through her mouth and put strange ideas in your mind.”

“Then where is Kuthulos?” asked Kull.

“He had disappeared when I came to Saremes’ chamber, and–”

“Ho, Kull!” a cheery voice boomed from the door and a bearded elfish figure strode in, accompanied by a slim, frightened girlish shape.

“Ka-nu! Delcardes–so they did not torture you, after all!”

“Oh, my lord!” she ran to him and fell on her knees before him, clasping his feet. “Oh, Kull,” she wailed, “they accuse me of terrible things! I am guilty of deceiving you, my lord, but I meant no harm! I only wished to marry Kulra Thoom!”

Kull raised her to her feet, perplexed but pitying her evident terror and remorse.

“Kull,” said Ka-nu, “it is a good thing I returned when I did, else you and Tu had tossed the kingdom into the sea!”

Tu snarled wordlessly, always jealous of the Pictish ambassador, who was also Kull’s adviser.

“I returned to find the whole palace in an uproar, men rushing hither and yon and falling over one another in doing nothing. I sent Brule and his riders to look for you, and going to the torture chamber–naturally I went first to the torture chamber, since Tu was in charge–”