Kull: Exile of Atlantis (26 page)

Read Kull: Exile of Atlantis Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

II

“

THEN

I WAS THE LIBERATOR–

NOW

–”

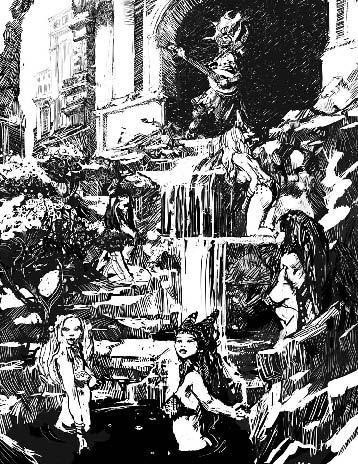

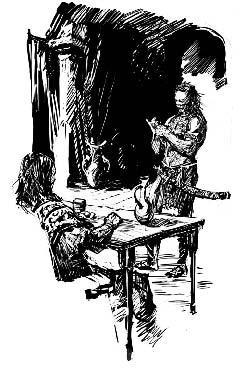

A room strangely barren in contrast to the rich tapestries on the walls and the deep carpets on the floor. A small writing table, behind which sat a man. This man would have stood out in a crowd of a million. It was not so much because of his unusual size, his height and great shoulders, though these features lent to the general effect. But his face, dark and immobile, held the gaze and his narrow grey eyes beat down the wills of the onlookers by their icy magnetism. Each movement he made, no matter how slight, betokened steel spring muscles and brain knit to those muscles with perfect coordination. There was nothing deliberate or measured about his motions–either he was perfectly at rest–still as a bronze statue, or else he was in motion, with that cat-like quickness which blurred the sight that tried to follow his movements. Now this man rested his chin on his fists, his elbows on the writing table, and gloomily eyed the man who stood before him. This man was occupied in his own affairs at the moment, for he was tightening the laces of his breast-plate. Moreover he was abstractedly whistling–a strange and unconventional performance, considering that he was in the presence of a king.

“Brule,” said the king, “this matter of statecraft wearies me as all the fighting I have done never did.”

“A part of the game, Kull,” answered Brule. “You are king–you must play the part.”

“I wish that I might ride with you to Grondar,” said Kull enviously. “It seems ages since I had a horse between my knees–but Tu says that affairs at home require my presence. Curse him!

“Months and months ago,” he continued with increasing gloom, getting no answer and speaking with freedom, “I overthrew the old dynasty and seized the throne of Valusia–of which I had dreamed ever since I was a boy in the land of my tribesmen. That was easy. Looking back now, over the long hard path I followed, all those days of toil, slaughter and tribulation seem like so many dreams. From a wild tribesman in Atlantis, I rose, passing through the galleys of Lemuria–a slave for two years at the oars–then an outlaw in the hills of Valusia–then a captive in her dungeons–a gladiator in her arenas–a soldier in her armies–a commander–a king!

“The trouble with me, Brule, I did not dream far enough. I always visualized merely the seizing of the throne–I did not look beyond. When king Borna lay dead beneath my feet, and I tore the crown from his gory head, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. From there, it has been a maze of illusions and mistakes. I prepared myself to seize the throne–not to hold it.

“When I overthrew Borna,

then

people hailed me wildly–

then

I was the Liberator–

now

they mutter and stare blackly behind my back–they spit at my shadow when they think I am not looking. They have put a statue of Borna, that dead swine, in the Temple of the Serpent and people go and wail before him, hailing him as a saintly monarch who was done to death by a red handed barbarian. When I led her armies to victory as a soldier, Valusia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner–now she cannot forgive me.

“And now, in the Temple of the Serpent, there come to burn incense to Borna’s memory, men whom his executioners blinded and maimed, fathers whose sons died in his dungeons, husbands whose wives were dragged into his seraglio–Bah! Men are all fools.”

“Ridondo is largely responsible,” answered the Pict, drawing his sword belt up another notch. “He sings songs that make men mad. Hang him in his jester’s garb to the highest tower in the city. Let him make rhymes for the vultures.”

Kull shook his lion head. “No, Brule, he is beyond my reach. A great poet is greater than any king. He hates me, yet I would have his friendship. His songs are mightier than my sceptre, for time and again he has near torn the heart from my breast when he chose to sing for me. I will die and be forgotten, his songs will live forever.”

The Pict shrugged his shoulders. “As you like; you are still king, and the people cannot dislodge you. The Red Slayers are yours to a man, and you have all Pictland behind you. We are barbarians, together, even if we have spent most of our lives in this land. I go, now. You have naught to fear save an attempt at assassination, which is no fear at all, considering the fact that you are guarded night and day by a squad of the Red Slayers.”

Kull lifted his hand in a gesture of farewell and the Pict clanked out the room.

Now another man wished his attention, reminding Kull that a king’s time was never his own.

This man was a young noble of the city, one Seno val Dor. This famous young swordsman and reprobate presented himself before the king with the plain evidence of much mental perturbation. His velvet cap was rumpled and as he dropped it to the floor when he kneeled, the plume drooped miserably. His gaudy clothing showed stains as if in his mental agony he had neglected his personal appearance for some time.

“King, lord king,” he said in tones of deep sincerity. “If the glorious record of my family means anything to your majesty, if my own fealty means anything, for Valka’s sake, grant my request.”

“Name it.”

“Lord king, I love a maiden–without her I cannot live. Without me, she must die. I cannot eat, I cannot sleep for thinking of her. Her beauty haunts me day and night–the radiant vision of her divine loveliness–”

Kull moved restlessly. He had never been a lover.

“Then in Valka’s name, marry her!”

“Ah,” cried the youth, “there’s the rub. She is a slave, Ala by name, belonging to one Volmana, count of Karaban. It is on the black books of Valusian law that a noble cannot marry a slave. It has always been so. I have moved high heaven and get only the same reply. ‘Noble and slave can never wed.’ It is fearful. They tell me that never in the history of the empire before has a nobleman wanted to marry a slave! What is that to me? I appeal to you as a last resort!”

“Will not this Volmana sell her?”

“He would, but that would hardly alter the case. She would still be a slave and a man cannot marry his own slave. Only as a wife I want her. Any other way would be hollow mockery. I want to show her to all the world, rigged out in the ermine and jewels of val Dor’s wife! But it cannot be, unless you can help me. She was born a slave, of a hundred generations of slaves, and slave she will be as long as she lives and her children after her. And as such she cannot marry a freeman.”

“Then go into slavery with her,” suggested Kull, eyeing the youth narrowly.

“This I desired,” answered Seno, so frankly that Kull instantly believed him. “I went to Volmana and said: ‘You have a slave whom I love; I wish to wed her. Take me, then, as your slave so that I may be ever near her.’ He refused with horror; he would sell me the girl, or give her to me but he would not consent to enslave me. And my father has sworn on the unbreakable oath to kill me if I should so degrade the name of val Dor as to go into slavery. No, lord king, only you can help us.”

Kull summoned Tu and laid the case before him. Tu, chief councillor, shook his head. “It is written in the great iron bound books, even as Seno has said. It has ever been the law, and it will always be the law. A noble may not mate with a slave.”

“Why may I not change that law?” queried Kull.

Tu laid before him a tablet of stone whereon the law was engraved.

“For thousands of years this law has been–see, Kull, on the stone it was carved by the primal law makers, so many centuries ago a man might count all night and still not number them all. Neither you, nor any other king, may alter it.”

Kull felt suddenly the sickening, weakening feeling of utter helplessness which had begun to assail him of late. Kingship was another form of slavery, it seemed to him–he had always won his way by carving a path through his enemies with his great sword–how could he prevail against solicitous and respectful friends who bowed and flattered and were adamant against anything new, or any change–who barricaded themselves and their customs with traditions and antiquity and quietly defied him to change–anything?

“Go,” he said with a weary wave of his hand. “I am sorry. But I cannot help you.”

Seno val Dor wandered out of the room, a broken man, if hanging head and bent shoulders, dull eyes and dragging steps mean anything.

III

“I THOUGHT YOU A HUMAN TIGER!”

A cool wind whispered through the green woodlands. A silver thread of a brook wound among great tree boles, whence hung large vines and gayly festooned creepers. A bird sang and the soft late summer sunlight was sifted through the interlocking branches to fall in gold and black velvet patterns of shade and light on the grass covered earth. In the midst of this pastoral quietude, a little slave girl lay with her face between her soft white arms, and wept as if her little heart would break. The bird sang but she was deaf; the brook called her but she was dumb; the sun shone but she was blind–all the universe was a black void in which only pain and tears were real.

So she did not hear the light footfall nor see the tall broad shouldered man who came out of the bushes and stood above her. She was not aware of his presence until he knelt and lifted her, wiping her eyes with hands as gentle as a woman’s.

The little slave girl looked into a dark immobile face, with cold narrow grey eyes which just now were strangely soft. She knew this man was not a Valusian from his appearance, and in these troublous times it was not a good thing for little slave girls to be caught in the lonely woods by strangers, especially foreigners, but she was too miserable to be afraid and besides the man looked kind.