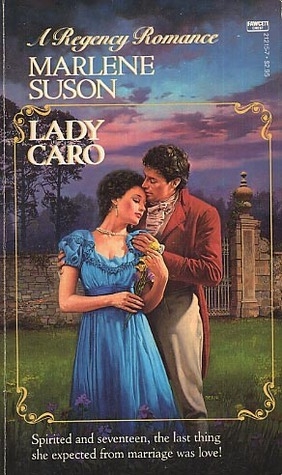

Lady Caro

Authors: Marlene Suson

LADY CARO

Marlene Suson

THEIR MARRIAGE WAS IDEAL IN EVERY WAY—EXCEPT HER HUSBAND’S HEART BELONGED TO ANOTHER!

Handsome, rakish Ashley Neel needed a wife to give him an heir. Lady Caroline Kelsie, a hoydenish miss with a mind of her own, needed a husband to save her fortune from scheming relations.

Alas, poor Caroline soon discovered her heart was not Immune to her husband’s considerable charms. But Corinthians like Ashley did not fall in love with antidotes such as herself...especially when his heart belonged to a woman he could not have.

How could he have foreseen that this duckling bride would bloom into a swan—and become the toast of London? Or that a marriage of convenience would prove to be something quite different indeed?

To my parents

Chapter 1

Returning from a late-afternoon ride in Hyde Park, Viscount Vinson found his servants, under the flustered eye of his usually imperturbable butler, rushing about his elegant residence in Curzon Street as though calamity had struck in his absence.

Even more astonishing, Vinson’s haughty valet, Swope, was actually carrying a portmanteau upstairs. Normally Swope, who was considerably higher in the instep than his employer, would have been mortally affronted at the suggestion that he, rather than a lower servant, perform such a demeaning task.

When Vinson inquired of Boothe, his harassed butler, what had thrown his usually serene household into such turmoil, he was told, “The earl arrived not above a half hour ago.”

“Good God!” exclaimed the startled viscount, immediately understanding the uproar. Even with advance warning of a visit, his demanding, high stickler of a father always managed to turn the house upon its ear when he arrived. “Why has he come?”

“As to that, I cannot say,” Boothe replied.

“Is my mother with him?”

Boothe’s correct voice took on a woeful overtone. “I fear he did not bring the countess with him.”

Traveling without his wife was guaranteed to put the earl of Bourn in a miff even if the journey did not. To the enormous relief of his servants, he rarely went anywhere without her.

An apprehensive frown marred the viscount’s usually amiable countenance. He must have done something that had put him in his father’s black books. Nothing less than that would have induced Bourn, who disliked traveling as much as he disliked London, to make the tiresome journey to the city from his country seat in Suffolk—and without his wife.

Vinson’s dark suspicion became a certainty when Boothe said, “His lordship instructed that you are to go to him immediately in his apartments.”

The viscount nodded, heartily wishing he had accepted the invitation to an exceedingly dull house party that would have put him at this very moment in Lancashire instead of London.

Sympathy showed in the butler’s eyes as the viscount, clad in buff riding coat, leather boots by Hoby, and buckskin breeches, turned toward the stairs. The young master was in for a trimming, if Boothe knew the earl, and Boothe

did

know him, having been in his employ these past thirty-five years.

The young master was a relatively recent tenant of the earl’s London house. Eight months ago Ashley Neel, now Viscount Vinson, had succeeded to the title and the enormous expectations of his half brother William on the latter’s death in a curricle accident. His father had promptly insisted that Ashley’s furnished rooms in George Street would no longer do. The future earl must live at Bourn House.

The advent of this new resident had been a source of rejoicing among the servants. William, who had occupied the house for several seasons prior to his death, had been difficult to serve and impossible to please.

The half brothers had been as different as night and day. William had favored his late mother: serious, dutiful, and precise as a pin. Worse, he had been so full of his own consequence that he had been irritatingly pompous. Ashley, on the other hand, never took himself or much of anything else seriously. His easy manner and winning smile won him loyalty and quality of service from his inherited staff that would have astounded the late William.

Ashley had been gifted with his vivacious mother’s charm, irrepressible humor, social grace, and innate amiability. These blessings were coupled with a tall, muscular body, curly dark hair, and arrestingly handsome face with laughing, vividly green eyes and a noble nose. This felicitous combination of personality and appearance guaranteed that no man’s company was more coveted by shrewd hostesses and nubile young ladies of quality. Unfortunately for the latter’s aspirations, however, he enjoyed a most agreeable connection with Sir Fletcher Roxley’s lady, arguably the most beautiful woman in London, that had robbed him of any interest in acquiring a wife of his own.

The viscount climbed the stairs for the interview with his father as eagerly as a condemned man mounts the

Ty

burn gallows. The relationship between the autocratic earl and his son had been an uneasy one ever since, as an underage youth, Ashley had tumbled wildly in love and tried in vain to marry without his father’s approval.

When Ashley knocked at the earl’s apartments at the back of the house, his father’s gruff voice bade him to enter without inquiring as to his identity. The viscount steeled himself for the ordeal ahead.

To his surprise, he caught his normally impassive, ramrod-straight father slumped wearily on a green bergère chair by a window that overlooked a small garden. The earl looked so morosely unhappy and anxious that his son caught his breath. For a startled instant, Ashley wondered whether his father was dreading their impending interview as much as he was.

Seeing his son, the earl instantly straightened. All definable emotion vanished from a face whose most arresting aspect was a pair of thick black brows that slanted diagonally downward, giving it a habitually disapproving cast.

The viscount, forcing a smile to his lips, said lightly, “What a pleasant surprise to find you here.”

“I doubt it,” Bourn said with his characteristic bluntness.

It was not an auspicious start, but his son persevered. “What brings you on a surprise visit to London?”

“You, what else?” The earl gestured impatiently for his son to take a second green bergère chair pulled up near his own. He was a large man, powerfully built, and as tall as his slimmer son, who stood well over six feet. But age had made inroads. His face was lined; his hair had thinned and whitened. Although his hazel eyes had lost none of their shrewdness, they seemed faded, making his peculiar brows all the more prominent.

As Ashley seated himself in the designated chair, his father said abruptly, “Louisa gave birth to another girl two days ago.”

Louisa was the widow of Ashley’s half brother. Siring an heir had been the only thing that the estimable William had failed to do. Not that he hadn’t tried. Dutiful as always, he had married the woman selected for him by his father and produced a half-dozen progeny—all girls. At his death, his wife was increasing for a seventh time, and it had been hoped that a son might be born to him posthumously. But now the baby was another daughter.

“I am sorry,” Ashley sympathized. “I know how much you wanted it to be a boy.”

Since William’s death, the earl had become increasingly preoccupied with the succession. Should Ashley die without a male heir, both the earldom and the great fortune entailed with it would pass to Henry Neel, a distant cousin of dubious reputation, a possibility that revolted Ashley’s father.

The earl said sternly, “You are eight and twenty, Ashley. It is long past time that you did your duty by marrying and producing sons. I shall not have Henry Neel inherit. William’s killer will not benefit from his death.”

Ashley winced. He found it difficult to believe that his rakehell cousin, whatever his other failings, could be a murderer. Unlike William, who had loathed Henry with an unreasoning passion and cut him at every opportunity, Ashley had always been friendly with his cousin and had even loaned him money on occasion. Although Henry had a wicked reputation with women and cards, he was also amusing, if overly cynical, and could be enormously charming. It was widely suspected, but never proven, that his remarkable success at cards was due to something other than luck. Having watched Henry play, Ashley had no doubt that his cousin was a cardsharp, but murder was quite a different matter.

Yet the earl, normally the most rational of men, was not one to make wild accusations. “Do you have new evidence indicating that Henry was responsible for William’s death?” Ashley asked.

“No, but Henry won a great sum by betting against my son in that fatal curricle race. Furthermore, it was Henry who proposed it and coaxed William into participating. It was not at all like him to gamble.”

That was true enough. But William was so inordinately (and unjustifiably) proud of his ability with the ribbons that his hated cousin could easily have teased him into accepting a wager that he would defeat Charles Bence’s new pair of grays.

During the race, a wheel on William’s curricle had come off as he rounded a curve, throwing him from his perch. Initially, his injuries were not thought to be fatal, but while recuperating he was stricken with a congestion of the lungs, which killed him.

An examination of the wheel revealed that it had been tampered with, but an inquiry into the tragedy produced no answers as to who was responsible for the sabotage.

“I could readily believe that Henry might try to fix a race,” Ashley said, “but I do not think him capable of murder.”

“Then you disappoint me,” his father said coldly. “However, I did not come here to discuss Henry’s guilt, but your lack of a wife.”

The viscount, who was lounging carelessly in his bergère chair, stiffened. “I fear the blame for that lies with you, not me.” Although he spoke lightly, his voice had a harsh overtone. “Had you not forbade it, I would have been married eight years ago to a lady who has since presented her lucky husband with three sons.”

“I forbade the woman, not the state.”

“But to me they were inseparably joined,” Ashley retorted. Eight years ago the beauteous Estelle Sutton had accepted Ashley’s offer. He had adored her, but she had been of less than distinguished origins, and her profligate family had not a feather to fly with. Her father, knowing her to be his only asset, had insisted on a very large sum from Bourn in return for her hand. The earl had flatly refused to pay it or to have Estelle as a daughter-in-law.

Ashley, who had been underage, would have defied his father by eloping with her to Gretna Green. But on learning that Bourn would cut off his second son without a penny if he married her, Estelle withdrew her acceptance and instead married Sir Fletcher Roxley, twenty years her senior but reputed to be the wealthiest man in London.

The brokenhearted Ashley was so unhappy and bitter about his father, whom he blamed for his loss of Estelle, that it was weeks before he could be induced to enter the earl’s company again. It took all of the countess’s great charm and persuasiveness to reconcile her son to her husband, but even after she succeeded, the relationship remained strained.

Although Ashley loved his father and had long since come to regret the breach between them, the fierce, formidable earl was not the kind of man either to express or to receive such sentiments. As the years passed, Ashley became increasingly certain that he was a bitter disappointment to his father.

After Estelle’s marriage, Ashley had tried in vain to forget her with a series of high fliers, but none of these beauties had succeeded in making him do so. Nor had any of the marriage-minded diamonds of the first water who had cast lures for him managed to win his heart. These incomparables and the birds of paradise who had been in his protection had all suffered from the same defect: They had cordially bored him after a few weeks.

Ashley’s father said bitterly, “Now you have taken up with Estelle again.”

The startled viscount wondered how his father had learned of the affair. Not that it was much of a secret, he concluded ruefully. He had attempted to be discreet for the lady’s sake, but she had shown no such inclination. Sir Fletcher Roxley had proven to be as disagreeable and boring as he was rich. After providing him with three sons, his wife had considered her marital duties fully discharged and looked elsewhere for romance. Discovering that her first love had matured into one of the most sought-after, sophisticated bachelors in London, she determined to recapture him and succeeded.

“Since Estelle is safely married, you have no cause to worry,” Ashley told his father.

“But you are not! Nor do you show any inclination to become so, with her back in your life. If you wish to spare me worry, you will take a wife.”

“There is no woman that I wish to marry.”

“Then your wishes be damned!” his father said impatiently. “It is your duty to marry a wife worthy of the honor of being countess of Bourn, and to do immediately.”

With difficulty, Ashley concealed his own rising temper behind an ironic rejoinder. “I fear I cannot think of a single young lady worthy of so great an honor.”

“I expected just such an answer,” the earl said with the air of a man whose darkest suspicions have been vindicated. He drew a paper from the inside pocket of his coat and waved it at Ashley. “That is why I have drawn up a list of seven young ladies who are acceptable.”

His son stared at the paper in disbelief. “I am no longer an underage youth whom you can command to do what you wish!”

To Ashley’s surprise, his father did not respond in his usual autocratic manner. Instead, he said unhappily, “It is not my intention to command you to do anything, and indeed I am not. The last thing on earth that I wish is to open another breach between us. But I am asking—indeed, begging—you to marry.”

The viscount was much moved by the earl’s conciliatory manner and his dread of another estrangement, a dread that was shared equally by his son. Ashley realized that he had been correct in his initial impression that his father hated this confrontation as much as he did.

“If William’s baby had been a boy, I would not force the issue now, but it is your duty as heir to marry and sire sons. I beg you to meet your responsibility by choosing one of these young ladies.” The earl again waved his list at Ashley. “You must save your family the disgrace of having the title fall into Henry’s hands.”