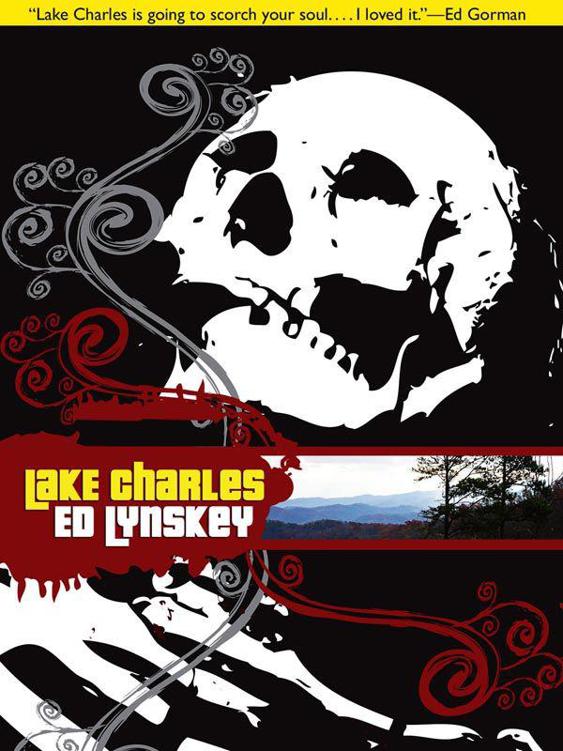

Lake Charles

LAKE CHARLES

ED LYNSKEY

Copyright © 2011 by Ed Lynskey.

All rights reserved.

The first chapter previously appeared in a different version in the

Dead Mule School of Southern Fiction Ezine

(2001). Thanks are extended to Valerie MacEwan, editor.

Edited by George H. Scithers

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

www.wildsidebooks.com

For Heather, with love always.

My twin sister Edna seated between Cobb Kuzawa and me snapped her gum. I drove my cab truck, its windows rolled down. The mountain air batting my face was a respite from breathing the ink fumes at Longerbeam Printery in Umpire. Again her gum snapped. Separated since July 4

th

, they’d yet to exchange a civil word. I’d cajoled her to tag along in hopes they’d bury the hatchet, if only for my peace of mind.

With my elbow jacked out the window, I wished an electric storm had knocked the dragonflies and gnats into Lake Charles, enticing the bass to surface feed and better our luck. Fishing was my all this Saturday morning, so I could forget my arrest for Ashleigh Sizemore’s murder. Yeah, right.

His mesh cap worn lopsided, Cobb was half in the bag. His forearm tattoo proclaimed, “EAT MORE BASS!” Ogling in his side mirror, he puckered up his fish lips. My eyes darted to the rearview mirror. A St. John of God (the patron saint of printers) medallion on a wax cord dangled from the mirror. The double decker trailer with our bass boats and Edna’s jet ski rode steady on my tow hitch. Then a red Cadillac slingshotted into the next lane and, ramping up, overhauled us. I backed off on the gas.

“Christ, did they rob a bank or jewelry store?”

The Cadillac bore out-of-state tags: New York. Tourists in 1979 came,

ogled our Smoky Mountains, and spent their greenbacks. These New Yorkers had spent loads on their gas. Their bumper stickers proclaimed, “HONK, IF YOU LOVE JESUS!” and “POW*MIA: Bring ’Em Home!” Cobb lunged over Edna and cuffed my horn to blare out. The four twenty-something males—the driver sported a Mohawk—paid us no mind.

“Was doing that necessary?” she asked.

Grunting, he shot me a rankled look. “I’d give my left kidney to tear into the mud bog.”

“Ha. All pigs like the mud.”

“

Oink, oink

. You’re the witch who changed me into a hog.” He shut his eyes, saying to me, “After we drop anchor, wake me.”

“Cobb was born a pig.”

“Just give me a straight razor,” I said when her tart glance expected my support. “Can’t you guys play nice?”

“Apparently we can’t.”

A cash-and-carry store, the white paint flaking off its clapboard siding, flew by us. I jotted a mental note for our future beer stop. It also had probably the only phone booth for miles around. Yesterday we had gotten a late start. An hour out of Umpire, our hometown not far from Gatlinburg, we’d decided to stop and chip in for a room. It was the motel’s last unit. A long workday had left us bushed. I registered us, and we crashed in front of a TV, its touchy vertical hold on Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Between his beer swigs, Cobb lectured as Cary Grant scrambled over the presidential mugs on Mount Rushmore.

“That rock sculpture tees off the local Injuns. They hold the Black Hills sacred.”

I yawned behind my wrist. “Is that a fact?”

“Now with his G.E.D., Cobb is the world’s authority on everything.” Her voice was testy. She glared at him sprawled on the foldout cot set up between our single beds. Her hand swatted off his empty PBR beer cans pyramidded on the bed table.

Oblivious to her jibe, he popped a new PBR. “Who can blame them? But they can’t do squat.”

“Sort of like me.”

Now he looked at her. “How is that?”

“I’m stuck between a rock and a sloppy drunk.”

Pleased to see his sour reaction, she wiggled over to face the wall. Her pale scalp at her ginger hair’s part reflected in the mirror-backed headboard. I noticed her yellow parrot barrettes on the bed table where the PBR cans had blocked them.

“Here’s a sobering idea: shut up.”

“What a ditz I was to ever marry you. Now quiet, all. I’m going to sleep.”

Tossing the empty PBR cans in the wastebasket, he grinned over at me. “What a conjugal bliss it was.”

She scoffed through her nose.

I put off the TV and lamp with a plea. “Can you guys cool it?” His saying “sure, mother” was the last thing I heard before I tumbled into a fitful sleep, and the same damn dream unfolded.

Ashleigh Sizemore radiant in the slinky purple gown sauntered from the pillars of smoke. Her smile beamed its come-hither look at me.

“Brendan, why am I dead?”

“I started to call an ambulance, but it was too late. You’d already died. Why does your father blame me?”

“Because you were the last person to see me alive

…

”

I jolted upright in the bed, my breaths in pants. The sheen of sweat pasted my forehead. I wiped it off. Saving her life had been futile. The M.E. said her PCP overdose was instant, but the damn PCP wasn’t ours, and I was no killer as charged. Feeling reassured, what did I do? If I snoozed again, I feared the same creep dream’s return would unglue me.

I staggered into the bathroom where its vent fan clanked away. My tingling fingers lay a lit match to a Marlboro. I inhaled, bagged the soothing nicotine, and exhaled smoke. I lived in a nightmare, branded as a killer, but now I was free on bail. The sheriff’s deputies could jug me again at any time. My second, deeper puff calmed my jangled nerves. I knew organic causes explained why the dead girl ransacked my dreams.

On the same day of my bail, I began my detox. The literature I’d sent away for said I’d encounter the all-too-vivid dreams the habitual pot users experienced after they went cold turkey. The THC (the kick-ass ingredient in the pot) in my fat cells had to sweat out before I’d be healthy enough to rest in peace. I mused on my present legal quandary.

My arrest for Ashleigh’s murder was three months ago in May. Cobb shared some blame for it, too. His dad Jerry Kuzawa and he had left to cut cypress downstate. Adrift without my sidekick, I hoped to inject a pulse into a dead Friday night, so I linked up with this crew.

We’d ridden in their party van over the mountains and heard The Devil’s Own, a musical hybrid of Pink Floyd and Foreigner, rock out in Yellow Snake. I flirted with this redhead—“Ashleigh,” she’d purred—in a shimmery, purple gown. The side-cut soared to her hips. I didn’t get her last name, just more leg than a hot-blooded lad should ever see.

By eight p.m., we filed into the Yellow Snake armory. She and I shared a spliff as The Devil’s Own cranked out their spacey music, and we cheered. Then she dug her hand deeper into my pocket. The pocket had a hole in it, and her hot fingers flowed like melted paraffin around my love bone …

Now the vent fan clattered in my ear as I pushed aside her murder and my arrest. I fixed on how I’d find my dad somewhere in the vast state of Alaska. My dilemma struck me as the kernel for a song, but I felt too uptight to scribble down any new lyrics. Instead, my old fears rolled out. I shuddered over my pulling any hard time at Brushy Mountain. Once thrown in prison, I’d glue a shiv to the sole of my foot or stuff the shiv up my bunghole. I’d slice up James Earl Ray leading the scar-faced felons out to trap and bugger me. Caged for the rest of my life behind steel bars, or a worse fate, drowned me in despair. I craved a joint. No, I had to resist my destructive habits. Get stronger.

Daybreak found me all smoked out, and I flushed the butts. I slipped on my boots and headed out to the ice machine. I hesitated since buying more PBR might tee off Edna, but I went ahead and topped off the Igloo cooler with ice. After returning to our room, boots still on, I tumbled into bed. She stirred in hers, and we slept on until the Hispanic housekeeper pecked her passkey on the metal door, murmuring at us.

“Psst, señora y señores, la sirvienta

…

”

* * *

My cab truck jounced off the state road and went down the bumpy lane to the oddly named Lang’s Teahouse. It sat on the north cape of Lake Charles, a TVA creation (we’d no natural bodies of water). Edna’s elbow jostled Cobb and he grumbled awake. The vista filled us with misgivings. First, the dance pavilion had gone to smash. As breezes rattled the candy-striped tin awnings, the past glories I’d grown up hearing arose in me.

Back in the day, the Chinese lanterns, tiki torches, and mirrored ball had illuminated the dance pavilion. Teenagers jalopied out of the hollows and hills to catch the rockabilly artists like Link Wray and Johnny Horton jam until dawn. The kids parked along the lane and out on the state road. Frisky couples danced on the teak floor, clapped for the encores, and later along the grab rail necked. The more wistful ones skimmed their coins over the water’s surface. A fortune in Liberty quarters, Mercury dimes, and buffalo nickels glimmered on the bottom of Lake Charles.

Hands over our noses, he and I slid out of the cab truck. The bilgy odor of decay filled the old marina. Half-sunken wood skiffs rotted in their slips like old dreams run aground. A skuzzy telephone booth near the pavilion tilted. We scared the muskrats to rustle under the loose planks. The T-dock slumped between the pilings and jutted out in the lake shallows.

“It doesn’t rate high in looks.” His strides moved a bit off-kilter since he’d mowed off a few toes while shod in flip-flops. Alcohol had been a factor.

“You said it.” My glance saw a set of horseshoe imprints left in the damp sand. “Does a horse trail run through here, Cobb?”

“I’ve heard Geronimo trots this way,” he replied, untangling his fishing lure.

She monitored the weather forecast on my radio. Scads of heat but little rain—it was August, the peak of the forest blaze season. The fires weren’t all bad. The paid firefighter crews bolstered the local economy, and I’d a notion the misguided arsonist lived in Umpire.

“That algae scum is thick enough to walk on.” A piece of a 2x4 I hurled into the shoal water and landing with a thunk reinforced my point.

“I’m so-o-o glad we came.” She approached us. “‘Lots of bass are biting,’ he tells us. ‘Lake Charles is a gas.’”

“Piss and moan,” he said, dismissing her sarcasm.

“Hey, it’s all good. Edna, what’s the forecast?”

“The next three days are sunny, clear, and hot.”

“Excellent. The prime fishing is out in the wide lake.”