Lamplighter (50 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

Each lighter was raised up on this small, worn platform. Poesides went first, and as the smallest Rossamünd was sent up next, finding the elevator more stable than it first appeared. He had no notion how Mama Lieger might operate this device if ever she left the house, but this pondering did not occupy his mind long. At the top he found a tiny front room—the obverse—with loopholes in the back wall and another solid door too, which was currently open. The woman was not there, though domestic bustle was coming from some rearward room. Rossamünd waited as the under-sergeant worked the mechanism that raised the platform. All present, Poesides led them through the second door to carefully deposit their burdens in a small closet at the end of a short, white hall.

“Ahh,” came that soft female voice, getting louder as the speaker appeared from a side door. “I must be thanking you once again for keeping a poor old einsiedlerin’s pantry full.”

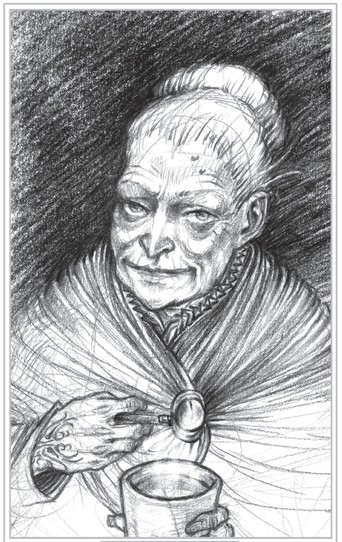

Bearing a tray of opaque white glasses, Mama Lieger turned out to be a neat, rather dumpy old lady, silvery tresses arranged in a precise bun, neither too tight nor too relaxed. Her homely clothes of shawl, stomacher-dress and apron were sensibly simple as was the interior of her humble dwelling. Run-down as it was, the parlor into which the men were invited was clean and tidy, any drafty holes plugged with unused flour-bags neatly rolled and wedged into the gaps. Yet for all this orderly homeliness there remained in her puddingy features evidence of the sharp, hawklike face she would have once possessed and a disquieting keen and untamed twinkle in her penetrating gaze—something deeply aware and utterly irrepressible. Serving them the piping, sharply spiced saloop the old eeker-woman looked Rossamünd over hat-brim to boot-toe. “Who is this new one, then?” she smiled, her expression most definitely hawkish. “Do they make lighters in half sizes now, yes? To take up less room in your festung—your fortress—yes?”

MAMA LIEGER

Poesides and the lampsmen gave a hearty chuckle.

“I—” Rossamünd fumbled for a proper response.

As she passed a drink to him, the young lighter noticed the hint of a dark brown swirl sinuating out from under the eeker-woman’s long sleeve, its style and color looking so very like a monster-blood tattoo. Rossamünd nearly missed his grip on the cup of saloop.

Mama Lieger noticed him noticing her marks and peered at him closely. “What a one you have brought me, Poesides.” The neat old lady’s wild, black eyes gleamed disconcertingly. “It is so very clear this one has seen his tale of ungerhaur; have you not, my little enkle, yes? Poor young fellow, I see the touch on him—I see he bears the burden of seeing like Mama Lieger sees, of thinking like she thinks, yes?”

Is she calling me a sedorner too?

Rossamünd looked nervously from her to his billet-mates: he did not relish being ostracized so early in his posting.

Rossamünd looked nervously from her to his billet-mates: he did not relish being ostracized so early in his posting.

“Aye, aye, Mama.” The under-sergeant came to his rescue. “Ye’d have everyone lost in the outramour if ye could,” he said tightly.

“That I would and the better for the world if you all were. Not to matter, you stay out here for a long time and the land will quietly speak to you—mutter mutter—the schrecken— the threwd—changing your mind: is that not right, my little enkle?” She peered at Rossamünd once more.

“I—ah—”

How can she talk such dangerous words so freely?

He wondered at the mild expressions of his fellow lampsmen, sipping tentatively at their piquant saloop and trying not to show how unpleasant they found it.

Why doesn’t Poesides damn her as a vile traitor and have her hanged from the nearest tree?

These fellows weren’t mindless invidists—monsterhaters—not at all. Rossamünd did not know what to think of them.

How can she talk such dangerous words so freely?

He wondered at the mild expressions of his fellow lampsmen, sipping tentatively at their piquant saloop and trying not to show how unpleasant they found it.

Why doesn’t Poesides damn her as a vile traitor and have her hanged from the nearest tree?

These fellows weren’t mindless invidists—monsterhaters—not at all. Rossamünd did not know what to think of them.

Apparently heedless, Mama Lieger sat in a soft high-backed chair and engaged the older fellows in simple chatter for a time, yet her shrewd attention constantly flickered over to Rossamünd.

Uncomfortable, Rossamünd looked at the mantel above the cheerily crackling fire. There he spied a strange-looking doll, a grinning little mannish-shaped thing with a big head and small body made entirely of bark and tufts of old grass. Even as he looked at it the smile seemed to expand more cheekily and, for a sinking beat, Rossamünd was sure he saw an eye open—a deep yellow eye that reminded him ever so much of Freckle.

The eye gave him a wink.

Rossamünd jerked in fright, spilling a little of his saloop.

All other eyes turned on him.

“Ye got the horrors, Lampsman?” Poesides asked in his most authoritative voice, a hint of disapproval in his eyes, as if Rossamünd’s behavior was a shame to the lighters.

“I—” was all Rossamünd could say for a moment. He gripped his startled thoughts and chose better words. “I have not, Under-Sergeant, I—I was startled by that ugly little doll,” he finished weakly.

“An ugly doll.” Poesides looked less than pleased.

Mama Lieger stood spryly. “He is never ugly!” she insisted, rising to stand by the wizened little thing. “My little holly-hop man. He is just sleeping his little sleeping-head.” She patted the rugged thing with a motherly “coo,” and turned a knowing look on Rossamünd.

He could not believe she was being so bold, nor that his fellows did not seem overly perturbed. Rossamünd looked fixedly into his glass of too-spicy, barely-drunk saloop and did not look up again till they were shuffling out of the room to leave. It was a relief to be going, despite the friendly threwd.The four made a hasty journey in the needling cold, Rossamünd as eager as the others to be home, back to the familiarity of the cothouse, their path easier for the lightening of their backs. He was glad too for the enforced silence to stopper his questioning mouth and for the distraction of the threwd growing less friendly again to occupy his troubled thoughts. With Wormstool clearly in sight, a dark, stumpy stone finger protruding high upon the flatland, Aubergene dared a quiet question.

“What were you getting all spooked at with that unlighterly display in front of the Mama, Rossamünd?”

Rossamünd flushed with shame. “That—that holly-hop doll moved, Aubergene,” he hissed. “It winked and grinned at me!” he added at the other lighter’s incredulous look.

“You’re a dead-strange one, Lampsman Bookchild.” Aubergene gave a grin of his own. “Maybe Mama Lieger is right and you can see like she sees?” He scratched his cheek with an open palm. “I’ve sure seen the dead-strangest occurrences since being out here; changes the way you think, it does. Perhaps you can put in a good word to the monsters for us too, ’ey?”

Rossamünd’s guts griped. Was the man being serious? Yet Aubergene’s grin was wry and teasing and Rossamünd grinned foolishly in return.

“Hush it the brace of ye!” Poesides growled. “Ye knows better . . .”

Of one thing Rossamünd was becoming more certain: he was quickly growing to like these proud, hardworking, simple-living lighters. He could begin to imagine a lamplighter’s life out here with them.

During their third week and an endless round of chores, Europe stopped by Wormstool, accompanied by a lampsman from Bleakhall as her hired lurksman. She had managed to persuade his superiors to release him to aid in her vital task of keeping the Paucitine safe—that was how she told it at least. Thoroughly impressed to be meeting the Branden Rose, the Stoolers joked with their Bleaker chum, declaring him the most fortunate naught-good box-sniffer in all the Idlewild.

“Aye, and I’m earnin’ more a day than ye all do in a month,” he bragged.

Europe ignored them as she spoke briefly with Rossamünd.

“Did you catch the rever-man?” was almost the first thing he said to her. “Was that your lightning we saw last week?”

“It might well have been. The basket was well knit and required a little more—push, shall we say. I never found out where it came from, though. Tell me,” she said, changing the subject, “are you happily established in this tottering fortlet?”

“Aye, happily enough,” Rossamünd answered. He wondered how he might fare trying to persuade Europe to hunt only rever-men.

Probably not well,

he concluded, and asked conversationally, “Have you been to the Ichormeer yet?”

Probably not well,

he concluded, and asked conversationally, “Have you been to the Ichormeer yet?”

“No.” Europe frowned quizzically. “There is no call to go picking fights one does not need.”

Threnody had come down to the mess but caught one glimpse of the fulgar, and with a polite grimace and a forced “How-do-you-do” went straight back up to wherever she had come from.

“How is our new-carved miss finding the full-fledged lighting life?” Europe asked amusedly.

Rossamünd watched Threnody’s petulant retreat. “I think she might be sorry for leaving Herbroulesse.”

Europe clucked her tongue. “The appeal of an adventurous life seldom lasts in the bosom of a peer’s pampered daughter.”

Rossamünd was not sure if the fulgar was talking about Threnody or herself.

“Tell me, Rossamünd, have you received any replies to your letters?”

It took a beat or two for the young lighter to realize she was talking of his controversial missives to Sebastipole and the good doctor. All the worry for Winstermill and Numps returned in a flood. “No,” he answered simply. What else to say?

Europe’s eyes narrowed. “Hmm.”

“What can it mean?” Rossamünd was suddenly afraid that he had done the wrong thing in sending them.

“Nothing,” Europe offered, her voice distant. “Everything. It probably simply indicates that your correspondents are too busy with their own affairs and, more so, that there is little they can do and little to be said as a result.”

“Oh.” His soul sank then lifted angrily. “There are times in the small hours I want to board a po’lent and hurry back to face Swill myself. I beat his rever-man and I can beat

him

too!”

him

too!”

“I am sure you can, little man,” Europe chuckled, “should you get that close . . . Keep at your work here, Rossamünd. Let the rope run out—they will eventually choke on deeds of their own invention. Such are the bitter turnings of Imperial politics: you have to endure much ill before you prevail. Pugnating the nicker is a much simpler life . . . and you live longer too,” she finished with a smirk.

After an exchange of respectful greetings with House-Major Grystle, Europe was soon on her way again, hired lamplighter lurksman in tow.

“I go to Haltmire now, to solve problems for the Warden-General,” she declared in farewell, adding quietly to Rossamünd, “It should prove to be an intriguing venture—I hear some distant grief has quite soured the Warden’s intellectuals. So wish me well.”

“Do well,” Rossamünd answered anxiously.

Her departure left a hint of bosmath and something for the lighters to talk about on the boring watches long after.

As for Threnody, the lamplighters of Wormstool themselves had scant clue how to live with a female in their number. Regardless they proved proud of her all the same. “Our little wit-girl” they called her, and would “ma’am” her wherever she went in the cothouse. They would grow shy when she descended to the well in the cellars to do her toilet, and some even doted a little, going to some lengths to make sure she had ample supply of parts for her plaudamentum and other treacles. At every change of watch, when the Haltmire lighters would arrive, the Stoolers would boast that they were better than their Limper chums, “ ’cause we have a wit!” That there were no others amazed Rossamünd. He had assumed lahzars would be standard issue on this leg of the Wormway, yet there were only two skolds at Haltmire and nothing better than a dispensurist at the four cothouses.

Clearly enjoying it, Threnody quickly grew comfortable with the attention. She took to wearing a pair of fine-looking doglocks in equally fine holsters at her hips, bearing them everywhere and playing the part of pistoleer at last.

“Where did you get

those

?” Rossamünd inquired one middens.

those

?” Rossamünd inquired one middens.

“Beautiful pieces, aren’t they?” The girl beamed.

He had to agree: they were indeed attractive, made of black wood and silver, every metal part engraved with the most delicate floral filigree, elegant weapons despite their heavy bore.

“Do you remember the prolonged stop we made at Hinkerseigh?”

“Aye.” He recalled most of all that she made them wait.

“These were why I was gone. I purchased them from Messrs. Lard & Wratch of Chortle Lane, finest gunsmiths in the Placidine.” Her beam widened. “I have longed for them for so long, looking in on them any time we made an excursion to that town.”

“How much did they cost?” he whispered. “How did you afford them?”

Threnody’s smile vanished. “Don’t you know that you

never ever

ask a woman how much

anything

costs!” she declaimed.

never ever

ask a woman how much

anything

costs!” she declaimed.

Rossamünd was sure that any regrets she might have had for coming to Wormstool were cured.

A common practice of a dousing lantern-watch was to leave the first two great-lamps on their route still undoused.These morning-lights were left glowing to provide a little light to the surrounds of the cothouse while the sun still tarried on the lip of the world. Part of this practice involved members of the day- or house-watch then going out and dousing them when the day-shine was brighter.

Other books

Rita Hayworth's Shoes by Francine LaSala

Steps to the Gallows by Edward Marston

Prague Fatale by Philip Kerr

The Sinister Spinster by Joan Overfield

The Purchase by Linda Spalding

The Night Monster by James Swain

Flesh by Brigid Brophy

Romani Armada by Tracy Cooper-Posey

Ravenous by MarcyKate Connolly

Elemental Assassin 02 - Web of Lies by Jennifer Estep