Lamplighter (61 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

Fransitart had become a wan gray.

Craumpalin had a haunted glimmer in his eye.

“Pray, Surgeon Swill, you must bring us to your point of view, sir—the morning runs long,” purred the Master-of-Clerks, a hint of chill in his voice, though he never let slip his patient façade.

“Most certainly, Marshal-Subrogat.” The surgeon bowed a third time to the Officers of the Board and went on as if he had not been interrupted. “But how can such a wicked abomination happen? I see the question clear on your corporate faces: how can a monster be found in the form of an everyman? As you are all well familiar, we know so little of the where and the why of the monsters, of how they perpetuate themselves.What we do know is that most teratologica survive so long they can be considered—as the short generations of men reckon it—to live forever.Yet the monsters

do

replace their numbers.We

know

some repeat themselves, budding like so many trees, dropping bits of themselves to grow into replicas of the original. This can be most commonly observed in the kraulschwimmen of the mares or the vicious brodchin of the wildest lands such as the Ichormeer or Loquor.”

do

replace their numbers.We

know

some repeat themselves, budding like so many trees, dropping bits of themselves to grow into replicas of the original. This can be most commonly observed in the kraulschwimmen of the mares or the vicious brodchin of the wildest lands such as the Ichormeer or Loquor.”

Here Swill paused, took a breath.

An awful, sick sensation was blossoming in Rossamünd’s gut.

Everyone expectant, the surgeon poured himself some wine from a sideboard, drank it all and continued.

“But what we have never seen is the creation work of the ancient gravid slimes, those places said to have been the nurseries of the earliest monsters, the eurinines—the first monster-lords—and used by them in turn to bring forth the lesser types of the theroid races.” As he went on, a quaver of fervent enthusiasm entered the surgeon’s voice. “Some of you might even know the history that was before history, the rumors of the beginnings; that these eurinines were granted by the clockwork of the universe to be able to put forth their threwd and make the muds fertile. Heated by the sun, worked on by the threwd, the very ground was made womblike and would pop to bring forth from the foul cesspits of the cosmos many of the worst and most notorious of the monsters that still stalk this groaning world today.”

Rossamünd did have some small understanding of the things said, but he had never heard the most ancient of histories put so directly. If he had not been in such a great anxiety, he would have eagerly listened to Swill wax learned like this for hours.

Wiping his mouth, Grotius Swill took up the cause once again. “Now these gravid muds continued to be used by the monster-lords, even through the rise and fall of ages, whereby they take the remains of some fallen nicker and bury them in the slimy womb-earth. After a time this spews forth some vital regeneration of those parts, another full-fledged monster to terrorize the homes of men.” He looked about shrewdly.

Not one person moved. Swill had intrigued them all.

“But here is the rub, you see. The movements of the races of men and tribes of theroid, all those risings and fallings, have left many threwdishly fecund places untended by their monster-lords, deserted but still oozing with foul potential. Yet unattended and unchecked by a eurinine’s will, these most threwdish of places we seldom if ever dare to navigate can still produce life, making strange beasties of whatever creatures might fetch up and die there. This abominable process we learned few call abinition, and this, lords, ladies, gentlemen”—Swill raised a salient finger into the air—

“this

is how Ingébiargë was made: a woman, some woman, nobody knows who, three thousand years ago perhaps, dies in one of these gravid places and falls, her remains swallowed by the hungry ooze. Sometime later out comes—what?” The surgeon shrugged and stared at his audience expectantly.

“this

is how Ingébiargë was made: a woman, some woman, nobody knows who, three thousand years ago perhaps, dies in one of these gravid places and falls, her remains swallowed by the hungry ooze. Sometime later out comes—what?” The surgeon shrugged and stared at his audience expectantly.

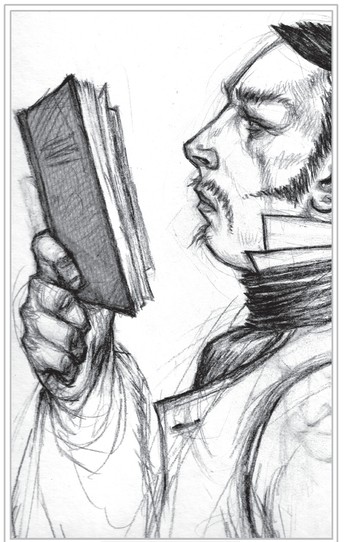

SURGEON

GROTIUS SWILL

GROTIUS SWILL

Expressions were blank, except Fransitart and Craumpalin: both were gray-faced, as ill-looking as Rossamünd felt. Despairing, Rossamünd looked to Europe. The fulgar was not paying him any mind, her astute, raptorial gaze fixed on the surgeon.

“Is it human? Is it monster? This thing sprung from the muds. We do not know for certain,” Swill pressed on, unaware of this calculating regard. “What we do know is that what is ‘born’—for the need of a better term—is reformed from the debris of human matter,

birthed

from the threwd, a wicked repeat of some lost and departed person. This we call a manikin, and whatever it might be, this reconstituted creature is certainly not human. I commend to you that if it is not human, then rationally it must be monster, and even if it is not, a manikin is not something we want walking free among us.” He paused and looked about the room with evident academic pleasure. “In the case we have before us today, things, I fear, go much deeper than simple sedonition. Rather, events must have proceeded upon similar particulars as I have just related. In some blightedly threwdish dell in the hinterlands of Hergoatenbosch, some poor lost fellow dies and falls. His remains are sucked up by the mud and slowly, by action of heat and threwd, maybe over centuries, they are remade, an abominable simulacrum birthed from the loam; another manikin. And what becomes of it? This manikin is somehow found and taken to a wastrel-house in the city to be raised as an everyman.Yet it is, in fact,

not

one of us at all.”

birthed

from the threwd, a wicked repeat of some lost and departed person. This we call a manikin, and whatever it might be, this reconstituted creature is certainly not human. I commend to you that if it is not human, then rationally it must be monster, and even if it is not, a manikin is not something we want walking free among us.” He paused and looked about the room with evident academic pleasure. “In the case we have before us today, things, I fear, go much deeper than simple sedonition. Rather, events must have proceeded upon similar particulars as I have just related. In some blightedly threwdish dell in the hinterlands of Hergoatenbosch, some poor lost fellow dies and falls. His remains are sucked up by the mud and slowly, by action of heat and threwd, maybe over centuries, they are remade, an abominable simulacrum birthed from the loam; another manikin. And what becomes of it? This manikin is somehow found and taken to a wastrel-house in the city to be raised as an everyman.Yet it is, in fact,

not

one of us at all.”

There was a baffled pause, people’s faces intent or dumbly wondering.

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, we all know the name Rossamünd—a sweet and apt name for some lovely, cherished girl . . . and, as it happens, the unfortunate and completely inapt name of this young lighter here”—Swill looked about keenly—“but who of you has heard of a rossamünderling?”

Vacant faces met him.

“None of you?” The surgeon’s satisfaction was evident. “I am not surprised; such a word has never appeared on any of the usual taxonomists’ lists. I, with all my reading, had not encountered such a word—until recently, that is, a happy accident of my persistent study. How does that interest us? Just so: Ingébiargë is a rossamünderling. All manikins are. You see, after much esoteric study I discovered in the most obscure of texts a most fascinating word:

rossamünderling.

It means ‘little rose-mouth’ or, more vulgarly, ‘little pink lips.’ More astonishingly yet, this word is a name the monsters of the east have for manikins.

Rossamünderling—

an ünterman in the appearance of an everyman. Rossamünd.” The man now pivoted on his heel, spitting in his passion, and pointed ferociously at Rossamünd. “For that is my point! That you—

YOU,

young Rossamünd whatever-you-are—you are that mud-born abomination! You are a manikin! You are a rossamünderling! A thrice-blighted wretchling in human guise!”

rossamünderling.

It means ‘little rose-mouth’ or, more vulgarly, ‘little pink lips.’ More astonishingly yet, this word is a name the monsters of the east have for manikins.

Rossamünderling—

an ünterman in the appearance of an everyman. Rossamünd.” The man now pivoted on his heel, spitting in his passion, and pointed ferociously at Rossamünd. “For that is my point! That you—

YOU,

young Rossamünd whatever-you-are—you are that mud-born abomination! You are a manikin! You are a rossamünderling! A thrice-blighted wretchling in human guise!”

There was a great shout of disbelief, of horror, from almost every throat in the room. Threnody jerked away from him, staring at him in dismay.

Rossamünd could barely breathe. He did not know whether to laugh or cry or shout down the surgeon’s foolishness. Mastering himself, he stood and looked to his old masters, and something in their eyes struck him more than any preposterous accusation of some strutting massacar. For their faces declared more eloquently than explanations that the words of Grotius Swill, secret maker of gudgeons and clandestine traitor to the Empire, might possibly be true.

Europe’s gaze was narrow and inscrutable as she peered at Rossamünd.

What does she think?

Laudibus Pile sneered, stroking his chin in wicked satisfaction.

The Master-of-Clerks actually managed to look stunned, and the Imperial Secretary with him.

“Yet if you need proofs of my logic, I simply quote this fine young peeress,” Swill pursued, “the daughter of the august of our very own faithfully serving calendars.”

The Lady Vey sat erect, her face hard and supercilious with hidden distaste, not giving a hint whose side she was for. She turned this brittle gaze to her daughter, and Threnody dropped her head, either unwilling or unable to look at Rossamünd.

“This fine girl speaks of his great destroying strength,” Swill continued, “a bizarre aberration that immediately piqued my curiosity.Then she explains of his habit of always hiding his smell behind a nullodor.

Why would one perpetually wear a nullodor,

I asked myself,

when one spends one’s life safe in the world of men?

And the answer came: unless you were trying to hide that you were not a man at all!” The surgeon said this last with a very pointed look at Rossamünd. “And

of course

you did not want to be marked with the blood of your own kind,” he cried, “for not only would the idea be repugnant, you

know

that on your flesh a dolatramentis

cannot show, for one monster’s blood will surely not make a mark on another!

”

Why would one perpetually wear a nullodor,

I asked myself,

when one spends one’s life safe in the world of men?

And the answer came: unless you were trying to hide that you were not a man at all!” The surgeon said this last with a very pointed look at Rossamünd. “And

of course

you did not want to be marked with the blood of your own kind,” he cried, “for not only would the idea be repugnant, you

know

that on your flesh a dolatramentis

cannot show, for one monster’s blood will surely not make a mark on another!

”

The young lighter’s thoughts reeled, and he blinked in dismay at the surgeon’s accusations.

“More so,” Swill pursued, “if what the august’s daughter says is true, then this one’s masters have conspired with it to hide its nature—a foul and deplorable act of outramour as has ever been documented!”

Fransitart and Craumpalin looked hard at the surgeon and refused to be cowed.

The Master-of-Clerks stared squarely at Rossamünd, a conquering glimmer in the depths of the man’s studied gaze. “What do you have to say for this, Lampsman 3rd Class?”

Rossamünd felt the blood leave his face and sweat prickle on his brow and neck. He could not let these puzzle-headed fallacies pass unchallenged. But what could he say to such outlandish poppycockery?

“Tell me, surgeon,” Sicus asked firmly, “how by the remotest here and vere do you propose to substantiate such a bizarre accusation? This young lighter as a sedorner is a charge I am prepared to hear out, but a monster who looks like a person! This is a

very

long line you plumb, sir. How do you intend to substantiate this obscure conjecturing?”

very

long line you plumb, sir. How do you intend to substantiate this obscure conjecturing?”

Swill balked, momentarily stumped, but rallied, a solution clearly blossoming in his thoughts. “If you would but indulge me just a little further, we could but take a little of this—this one’s blood; someone could be marked, and in a fortnight or so the proof would be there. Only a monster’s blood will make a mark on a person if pricked into the skin.”

Threnody gasped.

Sicus and Whympre and his staff were thunderstruck, and the Lady Vey too.

“I’ll not let ye cut ’im!” Fransitart cried, half standing but held back by Craumpalin.

Europe still did not move or comment, and the black-eyed wit kept his heavy-lidded scrutiny ever fixed on her.

To the universal surprise of the room, it was Rossamünd who spoke in Swill’s support. “Take my blood,” he said firmly, not quite believing what was coming out of his own mouth.Yet he was resolute. “How else can I show that this . . . that Mister Swill is wrong?”

“How else indeed? Bravely said, young fellow!” Swill enthused. “And to make it a truly impartial test, it would be best for one member each of the interested parties to be marked. In that way none can accuse the other of fabricating a result.”

“This is most irregular, surgeon,” Secretary Sicus cautioned.

“A serious and far-fetched charge has been laid at this young lighter, sirs,” the Lady Vey interrupted. “I say let a little blood be taken from him and the poor boy’s innocence and heritage be established.”

“As you wish it, m’lady.” Sicus nodded and made a dignified bow.

This sealed it.

Swill chose himself to represent the Empire and the lighters. Fransitart quickly offered himself on Rossamünd’s behalf.

A small dish, a small bottle, a guillion and an orbis were called for.

Grimacing, Rossamünd held out a finger, profoundly aware of the trust he was suddenly placing in a man he considered the blackest of all black habilists.

From the small bottle, Swill dabbed the young lighter’s fingertip with a thin, straw-yellow fluid, then dipped the guillion-tip in the same.

“This is libermane,” he explained to the room. “To make the sanguine humours flow easy.”

The surgeon deftly punctured Rossamünd’s fingertip with the guillion and more blood than Rossamünd expected began to drip out.

Feeling stupidly giddy, the young prentice let many drops of his blood splicker into the dish to form a little puddlet there.

“That will be sufficient,” Swill said when a coin-sized puddle of it had collected in the dish. With professional regard, he automatically passed Rossamünd a pledget to stanch the tiny wound.

“Hark ye, clever-cogs! I shall go first,” Fransitart insisted, looking very much as if he wanted to pound the surgeon to stuff. With a look of deep revulsion he removed his wide-collared day-coat and, rolling up the sleeve of his shirt, presented the inside of his wrist. “Right there’ll do fine, ye bookish blackguard,” he growled malignantly at Swill.

The surgeon swallowed nervously. “As you wish, Jack tar,” he answered and, taking up the orbis, dipped the guillion in Rossamünd’s blood and began to tap away on the old dormitory master’s blotched skin. Gripping the pledget to his finger, Rossamünd could not watch, and he looked up at the great antlers of the Herdebog Trought splayed above them. Even in these strange circumstances he still felt revulsion at the tap-tap-tapping of orbis on needle.

Other books

The Summer of Sir Lancelot by Gordon, Richard

Into The Fire by E. L. Todd

Body Politic by Paul Johnston

A Christmas Wish: Dane by Liliana Hart

Crystal Gardens by Amanda Quick

The Grand Duchess of Nowhere by Laurie Graham

Bad-Luck Basketball by Thomas Kingsley Troupe

Dreamwood by Heather Mackey

A City Called Smoke: The Territory 2 by Justin Woolley

The New Bible Cure for Depression & Anxiety by Don Colbert, Md