Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (18 page)

Read Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents Online

Authors: Minal Hajratwala

His life is a complicated example for me, its moments of shining idealism and sad compromise illustrating the relentless ironies of diaspora. Born a British subject, he helped his countrymen gain their freedom, only to die a British subject in yet another colony. Born poor, he became wealthy but died poor again. A man of strong principles, by the time of my mother's memory he was weak, often drunk, patriarch of a clan of merchants and traders, plagued by swindlers and cheats.

And yet that is not the whole story. One step out of India, he made the next possible. In Fiji his children went to missionary schools, where they studied the Bible and learned English. At home, they might sit on the floor and eat with their hands, but in school, they memorized how to set a table with two forks to the left, knife and spoon to the right. Decades later, armed with this knowledge, the two youngest would come to America. And their own children would treasure that jailbird photograph taken decades ago, the one that hints at another kind of man: a young revolutionary infused with the light of belief.

At the water's edge I stood alone for a few minutes, gazing at the orange sun sinking into the sea, trying to feel my Aajaa's spirit in the salt air. But spirits rarely come when called, and after a while, I turned back toward the darkening land.

It is almost impossible to like the Indians of Fiji. They are suspicious, vengeful, whining, unassimilated, provocative ... Above all, they are surly and unpleasant.

—James Michener,

Return to Paradise,

1951

I

F MY MOTHER'S PEOPLE

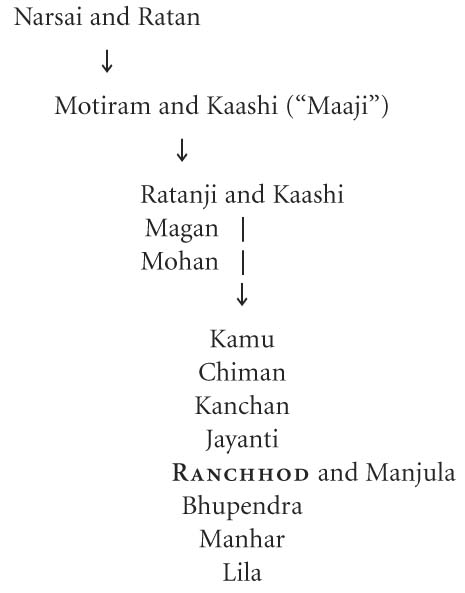

are quiet and humble, my father's are loud and brash—a clan of taletellers. For most of my life, the other descendants of Motiram Narsey have been strangers to me, with familiar faces (their resemblance to my father is strong) but unfamiliar temperaments. Far away in Fiji, they presided over the rise of a business that made our family's name so well known that even now it carries currency there, though all but a few have emigrated and more than a decade has passed since the Narseys department store shuttered its doors. Of the Narsey clan, the one I came to know best, through a few extended visits, was my uncle Ranchhod: my father's brother, and one of Motiram Narsey's grandsons.

He had a story for any occasion.

Speaking of spirits,

he might start up,

one time on a deserted jungle road in Papua New Guinea, we met two men. We were staying at the army base—they didn't have any hotels for nonwhites then—and we were just walking back from town. It was almost night. My friend had decided we should take the shortcut. I didn't want to, but he insisted. Suddenly two men appeared on the road. They were dressed all in white.

Here he would pause, just long enough to let the listener absorb the significance of this detail: they were dressed all in white.

Then one of them asked for a cigarette. I knew what he was, so I gave him my whole pack! And my matches, too.

— Where are you going? the ghost asked us.

—

Just to the base.

—

Go back the other way.

—

But this is a shortcut.

—

Sometime

—here my uncle's voice would drop ominously, the ghost still speaking in his own Indian-English accent—

shortcut never make it.

We were so scared! We turned around and went back the long way. It was dark now. When we finally got to our room, I stopped my friend from going in. I got some water and I said a prayer over it, and I sprinkled it on us. Like this.

And only then did I let him go in, and I went in myself, and thanked god for saving us from who knows what.

It is business that gives diasporas their strength and vibrancy, according to some economists: tight networks of kin across several continents are uniquely qualified to move goods and ideas, allowing ethnic diasporas to thrive in a global economy. But as any grandmother knows, it is story that truly holds a people together. When I asked my uncle Ranchhod what exactly his business entailed, he gave me a story.

It was hard to keep five thousand cartons of tinned salmon a secret, but Ranchhod was trying. The tins sat on the main dock of the Fiji Islands with his name on them, the key to his future success. The year was 1957, and the middle son of the Narsey family was embarking on an age-old Gujarati tradition called "middling": serving at the junction between producer and customer.

He had never tasted the pink fish from Canada. But he had come to know that Fijians savored it, so Gujarati shopkeepers all over the islands stocked it, each year importing the maximum allowed under the rules of the British Commonwealth—that final shadow of empire, whose regulations were carefully designed to maintain a delicate balance of trade between its nations and territories. A single white-owned company held a monopoly on importing salmon into the colony of Fiji. Now, Ranchhod was planning to ambush it and capture the trade. He was twenty-two years old, and motivated by debt.

He owed £150 to the family firm, which had just paid for his wedding trip back home to India and for his and his bride's passage to Fiji. He had a newly outfitted office with his name on the door: H

AZRAT

T

RADING

Co. Its ledger opened with £500 in its "Debts" column, start-up capital from the parent company, which he was required to pay back within a year. His salary was £30 a month. It did not take an accounting certificate, which he had, to calculate that he needed to make money quickly.

His assets were these: Business skills he had picked up during a prior six-year sojourn in Fiji, where he had arrived from India at the age of fifteen. A friend who suggested the salmon deal and told him which government official to bribe. Ambition. Youthful arrogance, perhaps even recklessness. A certain capacity to charm. And the five thousand cartons, which, he hoped, would pay off his debts, prove his mettle as a businessman, and earn him the praise of his father and uncles.

What he did not have was a truck to transport the salmon or a warehouse in which to store it. His conversational English, the lingua franca of business in Fiji, was minimal; on principle, he had refused to learn the language of India's oppressors. He had no financial reserves. And because this was not exactly the sort of business his elders had in mind—he was supposed to be a salesman, not an importer—he could not go to them for help. He wanted the deal to be a surprise. Once the profits were in, he reasoned, no one would carp over the details.

So he learned to wheel and deal. In exchange for a bottle of fine whiskey, a petty government official handed over the list of shopkeepers who had applied to buy salmon for the year. Ranchhod went to visit them one by one, persuading them to sign over their licenses to him as their receiving agent—a fellow Indian rather than a

goriyaa,

a white man. He wheedled a bank manager into advancing payment to the Canadians. He paid a white-owned agency to deliver the cartons to each shopkeeper and, though the agents did not normally do so, to collect payments as they went.

When the salmon reached its various destinations around Fiji and the checks started to come in, Ranchhod did not tally or record them; he took them directly to the bank. After some days, the bank manager called him:—What would you like me to do with the money?

—It's yours, said Ranchhod,—you take it.

—No, I took mine already. Your loan is paid, this is your profit.

—Oh!

He ordered the profit put into the Hazrat Trading Co. account, and went to report back to his uncle.—On five thousand cartons, he said, explaining the deal,—I have made a profit of £2,000.

—Impossible, said Uncle Magan.—Bullshit!

***

By the time Ranchhod told me the story almost fifty years later, it had been refined and perfected. The important thing was not the salmon and profits but the bragging rights: the

story

of the salmon and profits, the staging of the secret and its revelation for maximum effect and drama, both in the moment and ever after. The anecdote had become a

kathaa:

story, epic, ritual.

In its most formal incarnation, a kathaa is a ritualized recitation of a religious tale, extolling the feats or virtues of a particular god or goddess before an audience of the devout. But

kathaa

is also the everyday word for story, of various sorts:

panchaati,

gossip;

samaachaar,

news;

raavan-kathaa,

complaints of epic proportions; and

raam-kathaa,

a tale of heroic deeds. My uncle was a prodigious and entertaining storyteller, and in almost every story he told, he was the hero—which says something about either his character or his capacity for embellishment, or both.

The kathaa of the Narseys business, of which Ranchhod's tale was but a small piece, had been mostly a success story despite the death of its founder, Motiram, in 1918. Motiram's brothers had run M. Narsey & Company ably. They opened a grocery section briefly, then closed it to focus on the growing demand for their tailoring skills. They won a major government contract to sew police and military uniforms. Their biggest competitor, Walter Horne & Co., where the founder had gotten his start, closed down. And they brought their sons and nephews over from India to work for them.

Motiram's eldest son, Ratanji, had been just eleven years old when his father died, leaving his widowed mother, our Maaji, to manage the household. Maaji sent Ratanji to Fiji to work for his uncles when he turned fourteen. His two brothers soon followed. Upon coming of age, each of the boys went back to India to marry and then sojourned to Fiji again to work, leaving his bride in Maaji's care. In 1928, Ratanji's wife bore their first child. By the end of the decade, the company's profits were sustaining several households back in India.

By 1936, Gujaratis, who had started arriving in Fiji only three decades earlier, numbered 2,500, or three percent of the islands' total Indian population. As the Narseys and other Khatris came to dominate tailoring in Suva, a few men began bringing their wives and children to Fiji. They were making the shift from a bachelor society to one that included families, caste-based societies, and regular social and religious gatherings. In 1931, Ratanji's wife, Kaashi, came to Fiji, leaving their daughter at home in India with Maaji.

More children followed. Ranchhod, his parents' fifth child, was born in Suva on New Year's Day, 1935. His father, at twenty-eight years old, had already spent half his life in Fiji. But Kaashi never took to island life; four childbirths later, she wanted to go home. And Ratanji agreed, perhaps swayed by the fact that his earnings would go further in India, with its lower cost of living and the favorable exchange rate. Ranchhod was still in diapers when mother and children moved back to the village of Navsari.

They lived in a new four-story house of brick and cement, built with the Fiji money. Carved above the third-floor balcony, in the architectural fashion of the time, is the date of construction in two languages: the Gujarati year, 1993, and the English year, 1937. Three similar houses, built by Ratanji's brothers and uncles, stood nearby. They towered above the rest of the neighborhood with its single-story homes of wood, tin, and cow-dung plaster.

Ranchhod grew used to seeing his father once every few years, visits that were characterized by treats, arguments, and, afterward, the births of more children. His brother Jayanti cried and screamed each time their father left, so Ratanji sometimes departed in the middle of the night to avoid a scene. By the time Ranchhod was ten, he had two more brothers and a sister; his mother had also borne a son who died as an infant. The children split naturally into two groups, and Ranchhod was the youngest of the older set.

As World War II began, the Narsey brood enrolled in Public School No. 4. Before its end, thousands of Indians had died fighting for the Allies, a fact used by activists to bolster the moral argument for India's independence. Gandhi was more determined than ever to promote nonviolent struggle, but others were impatient with his methods. In the spirit of the times, Ranchhod and Jayanti joined a militant nationalist youth gang.

At ten and eleven, the boys were too young to be involved in the real action. But they made good, unobtrusive moles: They would go into the town's police station to beg a pencil or a newspaper or a piece of carbon paper, and as they hung around they would eavesdrop to find out whether the officers had any plans for, say, reacting to a demonstration the next day. Or they would be given mysterious parcels and told to tie them to the railroad tracks, small attempts at disrupting the British-run railroads. Whatever they understood of the politics, the gang's rebellious spirit excited them. And it fit Ranchhod's mischievous streak—one that frequently tested his mother's shallow reservoir of patience.