Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (2 page)

Read Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents Online

Authors: Minal Hajratwala

Finally, although sizable migrations have taken place

within

South Asia at various times (notably from India to Burma and Sri Lanka), I restrict my definition of the Indian diaspora to those who traveled

outside

South Asia. Re-migration from neighboring nations is frequent and difficult to track; to include these migrants might artificially inflate the diaspora figures, and I have chosen a conservative, if somewhat arbitrary, approach.

When rendering Indian languages in English script, scholars use diacritical marks to distinguish a hard

t

from a soft

t,

a long

i

from a short

i,

and so on. I find these marks minimally helpful for pronunciation, maximally confusing to the casual reader, and most bothersome to the noble typesetter and copyeditor, in whose good graces it is always wise to remain. So I prefer a phonetic approach. There is one significant vowel distinction, which I render as follows:

aa

for the long

a

(pronounced as in

father

), and

a

for the short, neutral

a

(as in

elephant).

For proper names, however, I follow common or traditional usage. Thus I write

Navsari, Gujarat, Hajratwala,

although these are pronounced

Navsaari, Gujaraat, Hajratwaalaa.

(For the very curious,

Minal

is pronounced

MEE-nalr;

it rhymes, roughly, with

venal,

not

banal.

)

My family speaks a village form of Gujarati, particular to our region and caste. Many of my interviews took place entirely or largely in this Gujarati. (Translations are mine, except as noted.) Speakers of a more formal version of the language may thus find "errors," as I have tried to render our folk speech faithfully, rather than "correctly."

Similarly, all beliefs, rituals, and superstitions described herein are particular to my people and, in some cases, only to my family. Despite the efforts of various sorts of charlatans, don't let anyone tell you they have the "correct" version of Hinduism. Hinduism is a vast, diverse religion; nothing depicted here (or anywhere) should be taken as a universal Hindu or Indian principle, for there is no such thing.

Finally, the reader should know that this is a work of nonfiction. I have been asked frequently whether I am fictionalizing, and the answer is no; whether I have changed people's names, and the answer is—except in one case, noted in the text—no; whether I am breaking or am tempted to break confidences, and the answer is no. The journalist in me is scrupulous about such matters, and no "poetic license" has been taken. Those family members who are main subjects and were alive at the time of the completion of the manuscript have had an opportunity to read their sections in advance and to correct matters of fact. All remaining errors are, of course, mine.

In rendering dialogue, I use quotation marks for words I have heard personally; some are translated by me. For bits of conversation that were related to me by one or more people who were present, I use the European system of dashes to introduce speech; the reader should take these words as conveying the sense, but perhaps not the exact text, of the conversation, which was sometimes being recalled many decades afterward. In this category, too, are the family letters rendered in Chapter 6 (Brains); the letters themselves, alas, no longer exist. For conversations described to me by someone who was not present, I do not attempt to quote directly. For internal thoughts or very lengthy anecdotes that were voiced in an interview with me, I use the person's exact words (sometimes in translation) in italics; otherwise, I do not attempt to reconstruct internal dialogue.

This book was eight years in the making, and to write it I interviewed nearly one hundred family members, friends, and community sources. I would not intentionally compromise their truth. Where their memories contradict one another, I have either made the differences transparent, or I have not included the incidents in question. In my heart the journalist and the poet hold hands and walk into the dark, each with her own methods, her own sticks and tools. It is for others to say how "literary" or "creative" they find this text; for myself, I am comfortable with the knowledge that it is, to the best of my capacity, simply nonfiction.

And inasmuch as the house of history is, like the house of dreams and other things of that sort, ruinous, apologies must be made for discrepancies.

—Abdul Qadir Badauni

1. WaterOn the sixth night Vidhaataa, Goddess of

Destiny, takes up what she finds below the

sleeping infant: awl and palm leaf under a string

hammock, or ballpoint pen and blue-lined paper

under a crib from the baby superstore.She eats the offering: sweets, coins.

She writes.Reviewing the accumulated karma of past lives,

enumerating the star-given obstacles of this one,

she writes.And what Destiny writes, neither human nor god

may put asunder.

The remnants of the Solanki dynasty were scattered over the land.

—James Tod,

Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan,

1829

"T

HE LAKE OF NAILS

is where your history begins," Bimal Barot tells us.

Dust filters through the half-light of afternoon. I am slightly nauseated, two days of traveler's sickness and a journey through winding alleyways—not to mention several countries, by now—having taken their toll. After interviewing relatives at half a dozen stops on my forty-thousand-mile-plus air ticket, piecing together the story of our family's migrations, I have come to India: to find whatever fragments remain here, to trace the shape of our past and learn how it shadows or illuminates our present.

Written records about private lives, though, are sparse. In English they come only from encounters with the colonial bureaucracy, usually at or after the moment of emigration. Before that, any information is kept in Gujarati, the language of our region, and in the Indian manner—which is to say haphazardly. Historical property records are inaccessible, but a date engraved on a house tells when it was built. Birth certificates may not exist, but an old lady's memory links a child's birth with a cousin's wedding with an eclipse of the moon.

But there is one objective Gujarati source, a collection of books filled with personal data. In the time before widespread literacy, one caste had access to the written word. Others, if they could afford it, paid these learned men to keep track of—or spruce up, if need be—their personal histories.

So I find myself sitting, with my parents, in the home of our clan's genealogist.

***

In a way it is astonishing that we have arrived here at all, on the strength of a name and a vague address given to me in Fiji weeks earlier by a distant uncle, who last used the information several decades ago:

Behind the Temple of Justice

Vadodara

Gujarat

INDIA

Vadodara is busy and industrial; home to 1.4 million, it is the third largest city in the state of Gujarat. Its air, which these days is a soup of diesel and factory fumes, was once so fragrant that it drew vacationers of the highest rank. The Prince of Wales, visiting in 1876, enjoyed the flowered breezes of the Garden Palace as a guest of the local maharaja—a kept man of the British Empire, who despite liberal inclinations squandered his people's money on luxuries and on making a good impression. For the English prince's visit, the maharaja ordered an honorary parade of soldiers, elephants with parasols, drums, spears, flowing robes, and horses kicking up dust. In this manner also, more pomp than substance, the maharaja ruled over the five villages where my ancestors lived.

The Temple of Justice turns out to be another of his old palaces, now repurposed as a courthouse. "Behind" means a neighborhood of gullies too narrow for our taxi to navigate. We transfer to a motorized ricksha to enter the maze, then stop and ask directions.

"The house is closed," someone calls out. One old woman sitting on a porch directs us left; her companion, equally wizened, points right. A boy hops into our ricksha and takes us to a house where after some time a man comes out. The boy runs off, the man hops in, we go back past the old ladies, one shouts a friendly, "Told ya so, this way," and so it goes till we reach a low-ceilinged house where a girl opens the door and, hearing the name we ask for, nods.

Inviting us in, she tells us the power has just gone out. Her father is not home right now, and he has the books. Still, she gestures for us to sit and wait, then withdraws behind a cotton curtain. We sit in the dim living room for several minutes, breathing deeply—a relief, after the ricksha's diesel fumes.

When the girl returns from the back of the house, she brings her uncle: a slim man with a full mustache and a few days' growth of beard, wearing a short-sleeved cotton shirt and a blue satin dhoti wrapped around his legs. He greets us and introduces himself. The name we came with is his grandfather's; his father is also dead by now; but he and his cousin, the girl's father, are keepers of the tradition.

To keep the records up to date, he explains, they—like their male ancestors before them—make their livelihood by traveling from town to town, recording new births, deaths, marriages, and sometimes emigrations, all for a fee. What they know of our community alone fills ten great books. He takes out another family's to show us what a book looks like: a huge, loose-bound sheaf twice as wide as an open newspaper, stained red at the edges. Upon closer examination, the stain turns out to be rows of red fingerprints, left by the powdery paste known as

kanku

with which the genealogists consecrate the pages during prayer. The oldest books are kept on bark.

I have already seen some of the names in the books.

In 1962, my father, a twenty-year-old amateur artist, drew a curving, flowering family tree. He was given the information by his father, who most likely purchased it from one of this genealogist's forefathers.

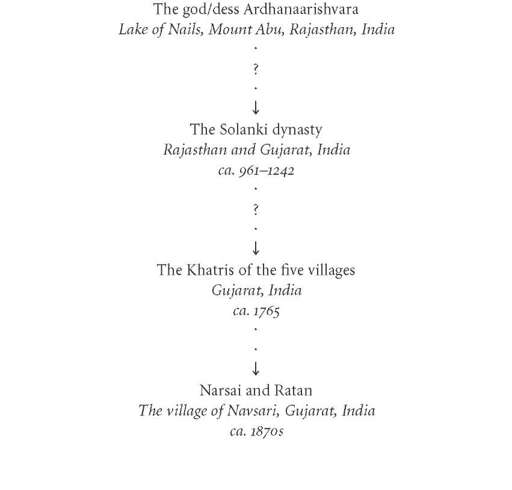

At the top of my father's drawing are a few pieces of data from antiquity. Some are obsolete: a word that identifies us with one of the seven original branches of humanity at the time of Creation, the name of our family physician in ancient days. Others continue to have ritual or practical use:

Kshatriya,

our caste, places us among the warrior-kings who are generally considered to be second of four in the hierarchical Hindu caste system: lower than the priests, higher than the merchants and the laborers. No relative in living memory was actually a warrior or a king, yet this caste identity persists, and continues to be held with pride.

Solanki

is our branch or clan. This is a kind of subcaste or lineage: the group of people we think of as our close relatives, a cluster of Kshatriyas who live in certain villages—five villages, to be precise—and with whom we share rituals and sacraments. It is this group for whom Bimal Barot and his family serve as record-keepers.

Our family goddess is

Chaamundaa.

To her we make offerings at weddings and births, that she might bring good fortune to all. Western books on Hinduism describe her as gory and gruesome: "emaciated body and shrunken belly showing the protruding ribs and veins, skull-garland ... bare teeth and sunken eyes with round projecting eye-balls, bald head with flames issuing from it..." But our goddess, at least the version represented by a statue in the village temple, is marble-skinned and rosy-cheeked, slightly plump and curvaceous in the manner of a maternal Marilyn Monroe. The benevolent smile she wears is, admittedly, at odds with the fearful scimitar and dagger she wields and the bloodied demon corpse at her feet.

Below these basic bits of information, in the neat, curling letters of our language, my father has inked thirteen generations of male names. Naanji, at the tree's root, rises thickly into his lineage of sons who begat sons. Halfway up the page, the tree begins to branch. The most prolific limb is that of Narsai, my great-great-grandfather.

I am interested in whether the genealogist has any further information about these ancestors. Any birth or death dates? Any tidbits on occupation, place of residence, fees paid? And—might the charts list the names of the women?

"Possibly," he says politely, which also means possibly not. He regrets that our books are traveling with his cousin just now; but for three thousand rupees, or sixty dollars, they will hand-copy our genealogies and mail them to us.