Lee Krasner (49 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

Mark Patiky is the only person to photograph Krasner while she painted. Patiky watched as she became very focused, standing back some fifteen feet with her arms folded, then running up and making “these slashing strokes,” a very active process, applied to unstretched canvas tacked to the wall. She is painting

Portrait in Green

(CR434), 1989.

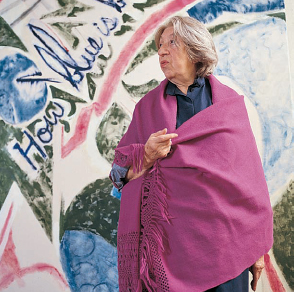

Here, Krasner in front of her latest painting, which she had made for “Poets and Artists,” an invitational show of forty-two artist-poet collaborations scheduled for Guild Hall that July. Krasner had teamed up with poet Howard Moss, whom she knew well through their mutual friend, Edward Albee. Lee Krasner standing in front of

Morning Glory

, 1982, oil on canvas, 84 x 60 in. Photograph by Ann Chwatsky.

IXTEEN

Recognition, 1965â69

Lee Krasner with her sister-in-law, Arloie McCoy; her nephew Jason McCoy; her great-nephew, Christopher Stewart; and his mother, Krasner's niece Rena Glickman Stewart (later Rusty Kanokogi), 1965, Springs. She invited her visitors into the barn studio to see new work and asked ten-year-old Chris what he would call her latest painting. He burst out, “Combat,” and she accepted the name at once.

K

RASNER MUST HAVE BEEN SURPRISED WHEN

B

ARNETT

N

EW-MAN

took up her cause in September 1965. He objected to a large exhibition called “New York School, First Generation: Paintings of the 1940s and 1950s,” which had been organized for the Los Angeles County Museum by its modern art curator, Maurice Tuchman, whom many came to dislike because of his repeated failure to include women or minority artists in

the shows he organized.

1

Newman criticized both the use of the term “New York School” and the inclusion of Clyfford Still and Ad Reinhardt in the show. Newman argued that both men were “on record more than once as being antiâNew York schoolâ¦. If this show truly represents the New York school, it is surprising to find them in and to find artists missing such as [James] Brooks, [Theodoros] Stamos, [Giorgio] Cavallon, [Conrad] Marca-Relli, [Jack] Tworkov, [Alfonso] Ossorio, [Esteban] Vicente, [Fritz] Glarner, [Ludwig] Sander, etc. and the ladies Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Hedda Sterne. All were active in New York during those important years.”

2

Of course, Krasner would have taken exception to Newman's categorization of “the ladies” as a separate group.

As for “New York school,” Newman declared, “This was never a movement in the conventional sense of a âstyle,' but a collection of individual voicesâ¦. The only common ground we all had is in the creation of a new, free, plastic language.”

3

For her part, Krasner insisted on individuality: “My painting is so autobiographical, if anyone can take the trouble to read it.”

4

Along the same lines, she penned in 1965 a dismissal of “problems in aesthetic, having only to do with the outer man. But the painting I have in mind, painting in which inner & outer are inseparable, transcends technique, transcends subject and moves into the realm of the inevitable.”

5

Given her aesthetic ideal of moving into the realm of the inevitable, Krasner relished the directness of children, who often seemed to understand her art. When, during the summer of 1965, she invited into the barn studio to see new work Christopher Stewart, her ten-year-old great-nephew, and his mother (her niece Rusty Kanokogi), she asked the boy what he would call her latest painting (70 by 161 inches). When he burst out,

“Combat,”

she accepted it at once.

6

It was the last painting she finished before her first show in London opened in the fall.

To name her pictures, Krasner often preferred the intuition of

children, poets, and novelists over that of dealers or critics. When Krasner's Detroit dealer, Frank Siden, supplied her with names for the new work, all gouache on paper, that she was including in her solo show at his gallery there in 1965, she rejected almost all of them, even though his choices alluded to forms in nature. For example, Siden's

Pertaining to Fauna

became her

Ahab

.

7

Krasner and Pollock had named their brown poodle Ahab after Captain Ahab in Herman Melville's 1851 novel

Moby-Dick

âthe book was read by many of their abstract expressionist acquaintances.

8

(Ahab's mission to get even with Moby Dick, the ferocious white whale that bit off his leg, must have appealed to Krasner's sense of tragic strife.) One of Siden's titles that she kept was

Night Creatures

. However, she did reject titles like

Bathsheba's Garden,

now known as

Summer Play,

and

First Step into Eden,

now known as

Autumnal

.

9

Either Krasner rejected these latter two names because of their references to the Hebrew Bible and her long discomfort with the attitude toward the female in traditional Jewish culture or she just found them too pretentious.

According to Sanford Friedman, Krasner once rejected

Entering Jerusalem

as a title for a painting that evoked a palm. “What are you crazy?” he exclaimed. “She didn't want anything Christian [Christ's entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday]; not that she had so much love for the Jews' Old Testament.”

10

Terry Netter remembers the time when Krasner came with Josephine Little to hear Netter preach at the Catholic church in East Hampton, then known as St. Philomena, even wearing a hat for the occasion.

11

When Netter decided in 1968 to leave the Jesuits and marry Therese Franzese, “the pretty sister of one of his students,” Krasner was supportive.

12

Apparently, “Therese loved her.”

13

Despite her skepticism about organized Judaism, Krasner saw herself as Jewish. “She made a point of making everybody know she was Jewish,” Netter recalls. And she remained fascinated with the appearance of Hebrew and other exotic writing. She continued

her interest in the visual form of writing systems in a painting of 1965 that she called

Kufic,

which is an ancient form of Arabic. Though painted on an ochre background, this large canvas continues the themes of her more hieroglyphic Little Image paintings during the late 1940s.

Krasner's interest in the forms of letters and the looks of different languages led her to attend lectures at the Morgan Library by the art historian Meyer Schapiro about the Book of Kells, a manuscript she revered.

14

In 1967, Krasner painted

Uncial,

a canvas named for the Latin term for the hooked medieval handwriting that she admired when she visited the Morgan Library to look at illuminated manuscripts.

Krasner's love of illuminated books and her admiration for the poet and critic Frank O'Hara led her to accept the Museum of Modern Art's invitation to participate in their publication

In Memory of My Feelings: A Selection of Poems by Frank O'Hara,

for which she produced a two-part drawing. O'Hara had written the first monograph about Pollock, which was published in 1959 by George Braziller. Krasner had been very positive about this book, preferring a poet's impressions over those of art critics.

15

On September 21, Krasner's first ever retrospective opened at London's Whitechapel Gallery. The organizer and gallery's director, Bryan Robertson, had already achieved what he had wanted with Pollock seven years earlier, so he clearly chose to organize Krasner's first retrospective with no hidden agenda. White chapel Gallery exhibited but did not collect art. From 1952 to 1968, when Robertson was in charge, he staged many other important shows, from the major American artists such as Mark Rothko and Robert Rauschenberg, to many emerging British artists, including Anthony Caro, David Hockney, and Bridget Riley.

In a brief preface for the show's catalogue, Robertson wrote, “[Krasner's] contribution to American painting has yet to be properly recorded or assessed: the present large exhibition rep

resents a fraction only of the total work.”

16

He also wrote, “In 1955 Lee Krasner held an exhibition of collages in New York which Clement Greenberg has described as a major addition to the American art scene of that era.”

17

Robertson's report seems likely to be accurate, because it was never repudiated by Greenberg, who notoriously wrote caustic letters denouncing material he considered false. In fact in a 1975 interview, Greenberg told Ruth Appelhof, then a graduate student, “I have always considered Lee's best period to have been in 1955. She developed a quality of humanness, an expansiveness, which could be seen not only in her personality but in her paintings as well.”

18

The catalogue also featured a much more substantial introduction by B. H. Friedman, who had earlier commissioned her mosaic murals for his company's building: “First, it must be said that Lee Krasner is a womanâin a field which still, even now in 1965, barely tolerates women, condescends to them with the phrase âwoman painter,' as odious and pejorative as âwoman writer' or âwoman driver.' In her work, Lee Krasner wants to be judgedâor, better, experiencedâas a painter. She wants no special categories. It may even be, whether consciously or unconsciously, that this is why she took the sexually anonymous name âLee.'”

19

Friedman showed cultural sensitivity in noting the androgynous character of the name, which others too have remarked on. Ironically, the nickname was used, if not coined, by her classmates at the Woman's Art School at Cooper Union and appeared in the student newspaper in the 1920sâat that time and in that place she surely had no reason to pretend to be male.

Robertson's young assistant, Tejas Englesmith, described the show at Whitechapel as “quite beautiful” and said that he “loved Lee.”

20

He remembered that “the Snowdons” (Princess Margaret and her husband, the photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, who was created Earl of Snowdon by the queen) came to see the show. Sir Kenneth Clark, whom she had met when she visited

London for the Pollock show in 1961, was supposed to take her to dinner but “rang the gallery to say that he had to cancel because Lady Clark drank a bit too much.”

Englesmith recalled that Krasner said to him, “I'm free. Are you free? So let's do something.” Krasner then changed a hundred dollars for pounds, which was “a lot of money in those days,” especially for a poorly paid assistant curator. Krasner handed him the money to take charge of and said, “Let's have a good time.” They went to dinner and then to see the Beatles' new film,

Help!,

with very good seats. For Krasner the film must have epitomized the youthful energy she felt in London, liberated from the constraints on her career that she had felt in New York. With her interest in primitive art, she must have loved the film's scene of exotic sacrifice. The evening ended with drinks at her hotel and her giving Englesmith money and urging him to take a cab home. He accepted her invitation to stay with her in New York. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

The show attracted a good deal of attention in the British press, but it was not initially about Krasner as an artist. Instead Krasner was heralded as “the widow of probably the most important artist that America has produced, Jackson Pollock.” Krasner told one reporter: “Things have been loaded against me in New York. Here I should get a fighting chance of some unprejudiced criticism.”

21

She exulted in the fact that she had arrived on the

Queen Elizabeth,

and that she was staying at the Ritz, which was a much fancier address than the apartment she then rented in New York at 70 East End Avenue. It was a remarkable contrast to the poverty she and Pollock had suffered. “In the 1930s and in New York, there were no galleries, no audience and nobody buying abstract paintings. We were pioneers. It was like trying to get up a mountain made of porcelain. There were just no finger holds.”

22

The reporter for the London

Sunday Times

mentioned that a good painting by Pollock “could fetch £100,000,” but that Pollock never got more than £1,000 for any of his paintings.

23

Krasner even told how she had quickly and unsuccessfully tried to resolve the Pollock estate: “I looked around for somebody to give the collection to, but nobody would take them unless I paid for the upkeep.”

24

When the reporter asked if it was not particularly tragic that Pollock was not around to reap the financial benefit of his work, she replied, “He had a high awareness of his own talent. The money would not have made much difference. It's just the way things are. When somebody comes along and opens a door, you can't expect everyone to see it. The next genius that comes along is not likely to be recognized in his own time.”

25

She claimed that despite the money, “she would still consider giving all her husband's paintings away, if they were properly housed.”

26

However, she reflected: “I know that having them [Pollock's paintings] means I am very rich. I can stay at the Ritz. That's the fun thing. But I could give it up. Caring for the paintings is a lot of worry.”

27

When a reporter asked Krasner how the exhibition happened, she responded: “I cannot say I chose to come here, as I was invited. But had I been able to choose, this is where I would have wanted to come.”

28

It was a good strategy. The reporter pronounced her “an important figure in American abstract painting” and noted that “a strong independent streak runs throughout her workâ¦. Her own talents as a painter, which are considerable as anyone who goes to the Whitechapel Gallery can see, have been overlooked.”

29