LEGO (32 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

The joint layouts of Dave and Stacy Sterling work because each of them has built a portion of their display. And that might be one of the main differences between creating as a child and creating as an adult. As we get older, it becomes more important to have creations and possessions that reflect our identity. I was comfortable at the Halloween party because building with LEGO is part of how I identify myself when talking to people. That’s why it’s time to acknowledge that there are two builders in our house. I won’t be the only one getting LEGO sets for Christmas.

22

You Can Go Home Again

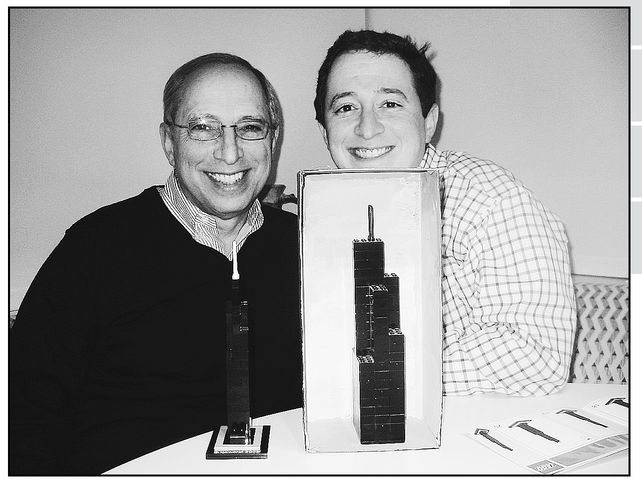

My dad, Jeffrey, and I pose proudly with our LEGO constructions—the Sears Tower we built when I was in the fourth grade and Adam Reed Tucker’s Brickstructures set.

It was after a visit to FAO Schwarz that I told my father I was going to be a master model builder. I had spent most of my time in the legendary Manhattan toy store staring at a towering giraffe made of LEGO. I was a ten-year-old with conviction. I made pronouncements. When you grow up in the state where the U.S. division of LEGO is headquartered, the possibility of working there doesn’t seem far-fetched.

It’s dark when I leave my childhood home to head toward my childhood dream job just four days after Thanksgiving.

And I have a nervous stomach as if I were showing up for the first day of work during the entire ninety-minute drive from Fairfield to Enfield, Connecticut. A pile of articles about LEGO Systems, Inc., the U.S. subsidiary of the LEGO Group, sits on the passenger seat. Thankfully, there is nobody to notice that I’ve been reading them at stoplights.

LEGO Systems is in Enfield, about twenty minutes north of Hartford and close to the Massachusetts border. As the buildings of Hartford give way to the bedroom community, I begin to see why LEGO executives might have chosen Enfield as their North American headquarters in 1975. It’s an Americanized Billund, with Bradley International Airport only thirteen minutes away in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.

I know I’ve arrived when I see the familiar tumble of three giant primary-color LEGO bricks. Steve Witt meets me at the door to walk me through the two-story building that houses the sales and marketing offices for North and Latin America. He stops before we get into his office and hands me a small plastic bag.

“Just don’t sell it, that’s all I ask,” says Steve, before I even know what he has given me. His request makes sense when I look down. In my hand is a chrome C-3PO, a limited-edition minifig randomly included in 2007 Star Wars sets. Only ten thousand minifigs were produced to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of

Star Wars.

I now have one of them.

Star Wars.

I now have one of them.

“I have no intention of selling it,” I tell Steve. The metallic gold figs sell for about $100 apiece on BrickLink or eBay.

“Good, then you won’t sell this one either,” says Steve. He hands me the chrome Darth Vader, which hasn’t even been released yet. Vader’s chest plate is stamped with a sparkly silver. It will be included in the 2009 Star Wars sets to honor the decade-long partnership between LEGO and the movie franchise.

“You’re kidding me. These are outstanding.” There is no doubt that I’m going to accept these. I feel none of the unease that bubbled up when Jan Christiansen tried to hand me a set in Denmark. I guess maybe I am kind of a Star Wars geek.

From the smile on Steve’s face, I can tell this is why he loves his job. For him this is like Wonka giving out golden tickets to the factory.

“It is pretty cool to know how happy this can make people,” says Steve as he walks me from the main building over to a secondary site where the call center and model shop are located. These two buildings are all that remain of LEGO Systems; LEGO’s presence in Enfield has shrunk considerably in the past several years.

The Enfield campus opened in 1975 and expanded to nearly 1.1 million square feet of commercial space by 2007. In January of that year, LEGO sold the 203-acre campus to Equity Industrial Partners for $58,880,848. In the wake of corporate restructuring, three hundred employees were laid off, and warehousing and packaging were moved to Mexico. The distribution center was relocated to Roanoke, Texas, and order fulfillment now originates in Memphis, Tennessee. As part of the sale agreement, LEGO leased back the two buildings we’re walking between. Having seen the production plant in Billund, I wish now that I’d seen LEGO Systems in its heyday, when the packaging plant filled the ten million square feet of space inside the distribution center with its fifty-foot ceilings.

Steve stops in to visit with the head of the call center; I stand outside the office, listening to the calls coming in to customer service representatives.

“Sure, we can get you that tire right away....”

“That’s a nice birthday gift....”

The voices float up from the rows of cubicles guarded by Bionicle creatures and minifigs. It’s as if a group of schoolchildren came to the office one day to decorate and nobody ever took down what they built. Somewhere in the cubicles is Steve’s wife, who has been working in the call center since they moved to Enfield from Texas.

We walk through another set of doors, and where I expect there to be offices is instead the bullpen of the model shop. The open studio could be an architect’s office with elevated desks, were it not for the LEGO sculptures covering every bit of shelf and table space. LEGO model designers Steve Gerling and Erik Varszegi are waiting for us. These are the same men who worked with Jamie Berard on the Millyard Project.

A row of life-size LEGO busts looks on as we are introduced. Steve Gerling notices my gaze, and the tour begins.

“The heads are still done by hand. The widths are within a six-stud range, and the eyes are usually four studs apart,” says Steve, to give me a sense of the yellow head he’s holding.

With a white beard and checked shirt, Steve, sixty, looks like an outdoorsman who’s been trapped at a desk job for the last eleven years.

“I’m new to building, having only started playing with LEGO bricks again six or eight months ago. I think I’m a long way from one of these,” I tell them.

“I never played with LEGO bricks before I walked through that door,” says Steve.

“It’s a generational thing. I might have had a few clone bricks when I was a kid,” says Erik. He’s tall and skinny with windblown brown hair. You wouldn’t know he was forty years old, if not for the few flecks of gray that have snuck into his goatee.

It’s surprising to learn that I’ve done more building than either of the two model designers did before setting foot in the model shop.

“There used to be a six-month training period, where you had to be taught building skills, repair, and regulations—like the height you can build before interlocking bricks,” says Steve.

Model trainees were then promoted to model builders, and after a year of building could attain master model builder status. The model shop here has a function similar to the designer Jette Orduna’s in Billund. They coordinate with marketing and sales to design and build models for publicity, charity, and corporate partnerships.

We’ve made it just fifteen feet inside the model shop when Steve Witt suggests we break for lunch. I only agree to leave when he promises we can return in the afternoon. Through a happy accident, we’re joined by three other model designers, and I’m stunned to find myself sitting down to lunch with five master model builders.

“There’s no cutting, altering, sanding, or carving,” says Steve Gerling when I ask if they’re LEGO purists.

I tell them the story of how I got started building with LEGO in the basement of my childhood home with my father. They all groan when I get to the part about my dad spray-painting the LEGO Sears Tower black.

“But he was the one holding the spray can,” I offer weakly. Apparently I should have known better, even if I was only in fourth grade. This is not going well.

I try to move the conversation forward. “You know, when I was in fourth grade, I thought I wanted to be one of you guys.”

“It’s funny you say that, because it seems like kids are always excited to meet a master builder,” says Dan Steininger, just back from leading the construction of an eight-foot pirate at the LEGO retail store in Orlando.

“You have kids walking around Disney with their autograph books, asking if they could get an autograph from the LEGO man,” adds Steve Witt.

“But what about when those kids grow up to be adults? What’s it like to build alongside adult fans?” I ask.

“When AFOLs come out for weekends, I look at them as coworkers. We’ve just worked a weekend together, but yet we have their dream job. We are those who are lucky enough to be paid by the LEGO Group,” says Dan.

The model builders nod their assent.

“There’s a real level of mutual respect. I love it too,” says Steve Gerling.

“We’ll pull up videos online, and what they build is amazing. You’ll see cows’ heads turning as a train goes by,” says Erik.

“I guess we just speak the same language,” says Dan.

“And yet we don’t—what we call roof tiles are slopes to adult fans,” counters Erik.

“Right, but everybody knows that a one-by-five is a hot girl at a LEGO event,” cracks Steve Witt.

“Is that code, or is that because it doesn’t exist?” I joke. LEGO only manufactures 1 × 4 and 1 × 6 bricks. They don’t make 1 × 5 bricks, so it’s the perfect way to acknowledge a hot girl without the public knowing.

Everybody at the table laughs. I feel like pumping my fist. When you can make people laugh, you speak their language. And once you speak their language, you’re ready to be part of the group.

After lunch, I feel comfortable standing behind Steve Gerling’s desk. This would be a good place to work. The shelf behind me has a LEGO bust of Scooby-Doo, a LEGO marlin, and a business card-size LEGO badge from BrickFest 2005, where Jamie Berard was offered a job by LEGO. Underneath the shelf is a series of gray bins with bricks sorted by color.

“My job isn’t creating art; it’s selling toys. I don’t expect any of my pieces to end up in the Louvre. I’m just making this thing that shows people: look at the kind of stuff you can build if you try,” says Steve, pulling up a three-dimensional image of a Cap’n Crunch model. The 3-D model is the cartoon picture of the cereal captain translated into a series of cylinders, cones, and squares.

“This program does not design a model for me, it makes designing a model faster for me,” says Steve.

Model designers will typically sketch a version of a project on paper before using the virtual tools. That is followed by the first stage of model review, where other designers weigh in on the prototype.

“A big part of our job is to criticize models as they are being built,” says Steve.

“If nobody is saying anything, then your model probably sucks,” Dan chips in as he walks by. He still has the comedic timing from having been a professional clown for over two decades.

After the model review, the designer might make changes to the model before it is fitted for a steel interior structure. The final version is then built and glued. Model designers attempt to build with as many current parts as possible, in order to maintain the idea that anyone could build what they build. They have a digital inventory of all of the current elements in production.

“What’s your favorite element?” asks Erik. I freeze up at the question.

“I call it a lunch box, it’s perfect for micro monorails,” I tell him. When I can’t find the words to describe the part, I draw it for him.

“Ah, it’s a one-by-two clamp,” says Erik after searching for a few minutes on his computer. “We have a bunch of those in back.”

The back of the model shop doubles as a parts warehouse. Shelves the color of old gray bricks have elements glued to the front to identify what is inside each bin. The Millennium Falcon sits casually on a table.

“It was broken in a shipment from a Denmark toy fair. Erik built that in a week with no instructions. All he had was a series of one-page photos,” says Steve.

I whistle like the sound of a bomb falling. I have never made this noise in my life in response to a statement, but it seems apropos. That’s the blind build on steroids. Putting together five thousand pieces without the instructions is impossible, like Luke Skywalker hitting the shot to blow up the Death Star.

Steve opens a door in the back left corner of the model shop, and we walk into a concrete storage room where I would not have been surprised to see the Ark of the Covenant. This is bulk storage, where plates and bricks are organized by color. An empty mail cart with a Red Sox cup holder is parked next to the shelves. I briefly entertain the idea of loading it with bricks and making a break for it.

“I think the company store is the last stop,” says Steve, flicking off the lights on millions of bricks.

The company shop is a small room with off-white shelves and the feel of an outlet store. It’s scratch-and-dent heaven. I tell myself I’m not going to buy much, seeing that I just spent $104 three days before on

LEGO.com

during the Brick Friday sale.

I need these three sets,

I said to myself. The first was the Custom Car Garage, which Joe Meno had told me about designing during my trip to Brick Bash back in March. The second was the Space Skulls set, another fan-designed set, which I had learned about from the New Business Group in Billund. And finally, Kate doesn’t have a set to build, so I wanted to get her the Creator Cool Convertible set, an oversize white car with a top that folds into the trunk.

LEGO.com

during the Brick Friday sale.

I need these three sets,

I said to myself. The first was the Custom Car Garage, which Joe Meno had told me about designing during my trip to Brick Bash back in March. The second was the Space Skulls set, another fan-designed set, which I had learned about from the New Business Group in Billund. And finally, Kate doesn’t have a set to build, so I wanted to get her the Creator Cool Convertible set, an oversize white car with a top that folds into the trunk.

Other books

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich

Trading Faces by Julia DeVillers

Eternal Promise (Between Worlds Book 3) by Talia Jager

The Leavenworth Case by Anna Katharine Green

In Too Deep by Dwayne S. Joseph

The Edge of Light by Joan Wolf

Blackstone and the Wolf of Wall Street by Sally Spencer

The Blood of Heaven by Wascom, Kent

Tengo que matarte otra vez by Charlotte Link

Roller Hockey Rumble by Matt Christopher, Stephanie Peters