Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Master (14 page)

Read Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Master Online

Authors: Ann Hood

“Where's that?” Maisie asked.

“You'll see,” he said.

They went down the Grand Staircase, across the foyer, through the West Rotunda with its glass-domed ceiling that revealed the full moon still in the sky above them, and into the Ladies' Drawing Room.

The Ladies' Drawing Room had pink moiré silk walls with twenty-four-carat-gold trim and a ceiling covered with murals of some Greek myth. Maisie and Felix hardly ever came in here. Everything was dainty and fragile-looking, from the desk with the spindly legs to the deep-pink fainting couch.

Great-Uncle Thorne paused.

“It's said that my mother loved this room,” he said wistfully.

Maisie glanced around it. A harp stood in one corner with a music stand in front of it.

“Did you know that every harp has a twin, cut from the same piece of wood?” Great-Uncle Thorne asked them.

But it seemed to Felix to be a rhetorical question, so he didn't respond.

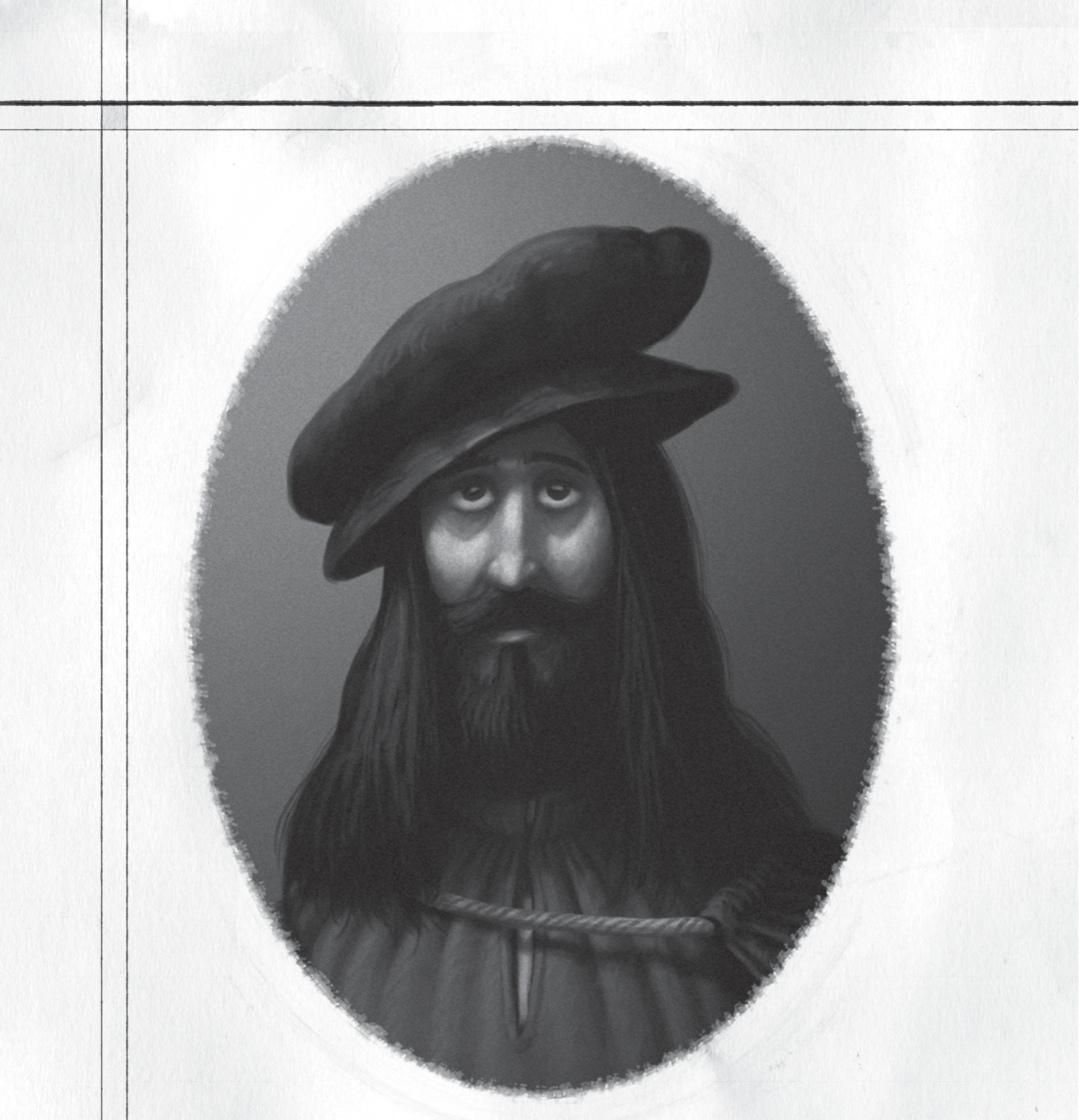

“Hey!” Maisie said, pointing to an oval painting on the south wall. “That's from the Palazzo Medici!”

“So it is,” Great-Uncle Thorne said with a chuckle. “My sister would be pleased that you are finally learning some culture.”

He moved slowly to the opposite wall.

On it were four large jewels.

“Are those real?” Maisie asked him.

Great-Uncle Thorne touched them in turn, saying what each was as he did.

“Emerald. Ruby. Sapphire. Diamond.”

He kept his hand on the diamond and gently turned it until that part of the wall creaked open.

“It's a door!” Felix said.

“The door to the Fairy Room,” Great-Uncle Thorne said, stepping inside.

Maise and Felix followed him, gasping as they entered.

The room was tiny, its walls covered with real ivy and pink and blue morning glories. The ceiling was covered in angel hair dotted with tiny twinkling white lights.

“The floor is made of grass!” Maisie exclaimed.

All of the furnitureâwhich wasn't very muchâglittered with gold.

There was a small love seat, and on that love seat sat the Ziff twins.

Rayne and Hadley jumped to their feet as soon as they saw Maisie and Felix.

“Isn't this room the most wonderful place you've ever seen?” Rayne said, giddy.

“My mother built this for the fairies,” Great-Uncle Thorne explained.

“Fairies,” Maisie said.

“Yes,” Great-Uncle Thorne explained. “In Victorian times, peopleâincluding my motherâwere fascinated with fairies and their lore. Someâalso perhaps including my motherâclaimed to see them. She built this room for them, putting all of their favorite things in it.”

“So they just flap their wings and fly in and out of here?” Maisie said sarcastically.

“Actually,” Great-Uncle Thorne said, “fairies don't have wings. They fly by magic. That is, if you believe in that sort of thing. As I said, many people in the Victorian era did.”

“Is that why we're all here?” Felix asked.

“Not at all,” Great-Uncle Thorne said. “I just wanted the most private place for us to meet and finally let the Ziff twins, here, tell us what happened when they found Amy Pickworth.”

Hadley began to talk right away.

“We saw her that very next day. She had on real bush gear. You know, khaki pants and a jacket with all these pockets and a big hat with, like, a veil over her face.”

“To keep out the mosquitoes,” Rayne explained.

“As we approached, she looked up from her workâ”

“She was very engrossed in it, drawing a map of some kindâ”

“âand she said, simply, âYou've come.'”

“We didn't know what to answer,” Rayne said.

“She did ask us what year we'd come fromâ”

“âand when we told her, she got so excited!”

“She couldn't believe it was the twenty-first century,” Hadley added.

“She asked about her children, and about Phinneas, and about history, too,” Rayne said, her words spilling out rapidly.

“Who was president and what had happened in a lot of countries and with a lot of people I'd never heard of,” Hadley continued.

“And then she said, âIt's time.'”

Maisie frowned. “It's time? That was her message?”

Rayne shook her head. “No. I asked her, âTime for what?'”

“And she said,” Hadley finished, “âWhy, time to open the egg.'”

“The missing egg!” Felix said.

“She took the map we had, the one from The Treasure Chest, and then we were back,” Rayne explained.

Maisie and Felix looked at Great-Uncle Thorne.

He stood tall, not at all bent or crooked, his eyes gleaming.

“Children,” he said, “it's time to open the egg.”

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Born: April 15, 1452

Died: May 2, 1519

L

eonardo da Vinci was born in the town of Vinci in the Republic of Florence, which is now part of the country of Italy. At the time, Italy was not united and was made up of many city-states, or republics. It was customary for people to take the name of their birth city, which is why Leonardo was known as da VinciâLeonardo from Vinci. Little is known of Leonardo's early life. His parents never married because they were from different economic and social classes. His mother was a peasant, possibly even a servant (though no one knows for sure). His father was a notary, which was similar to a lawyer. Leonardo lived with his mother until he was five and then moved to his father's family farm. Eventually, both of his parents married other people and had other children, giving Leonardo seventeen half brothers and sisters!

Leonardo did not have a formal education. But he began to draw the Tuscan landscape as well as the natural world around him on the farm at a very early age. He loved to read, and his grandfather taught him math and science. Through his love of observation, he taught himself astronomy, anatomy, and physics.

In 1468, Leonardo's family moved to Florence. At that timeânow called the Renaissanceâart was flourishing there. Leonardo's father helped get him an apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio, a painter, sculptor, and goldsmith who took many apprentices, including Sandro Botticelli. Artists were valued in Renaissance Florence, and the wealthy people there became their patrons, securing commissions for them and welcoming them into their homes.

An artist's apprenticeship followed a rigorous program. In addition to studying the fundamentals of painting, he studied color theory, sculpting, and metalwork. Leonardo studied with Verrocchio until 1472, when he was admitted to Florence's painters' guild. This gave him credibility and visibility to wealthy patrons. After five years with the guild, Leonardo opened his own studio, where he worked mostly with oil paints. At that time in Florence, the Medicis were the most important political family, and Lorenzo de' Medici became Leonardo's patron (he was also Michelangelo's and Botticelli's patron). However, Leonardo had a habit of not finishing work he'd begun, and soon Lorenzo ended his patronage.

In 1482, Lorenzo went under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, the future Duke of Milan. The Sforzas controlled Milan, but unlike the Medicis, who were bankers, the Sforzas were warriors, and Leonardo learned about machinery and military equipment in Milan. He served as the duke's chief military engineer and architect, but he also began

The Last Supper

, one of his most famous paintings, during this time. The duke commissioned it to be painted on the wall of the family chapel, which was thirty feet long by fourteen feet high. Due to the type of paint Leonardo used and the humidity in the chapel, the painting is extremely fragile and began to deteriorate almost immediately. In 1999, a restoration was completed, but very little of the original paint remains, and the expressions of the Apostles are difficult to make out.

In 1499, the duke was forced out of Milan, and King Louis XII of France took over all of his land. With the military experience Leonardo had gained with Sforza, he was able to get work with Cesare Borgia's army in 1502. Borgia was a notorious figure during the Renaissance. He allegedly killed his own brother, and many believe that Machiavelli based his book

The Prince

on Borgia. Although Borgia commissioned Leonardo to design bridges, catapults, cannons, and other weapons, he was also a patron of the arts, so Leonardo worked with him until 1503, when King Louis's governor made Leonardo the court painter in Milan.

Under King Louis, Leonardo continued to do military and architectural engineering in addition to painting. But he was also able to continue his studies in anatomy, botany, hydraulics, and other sciences. In 1513, King Louis XII was forced out of Milan, thus ending Leonardo's role in his court and freeing him to return to the Medici patronage. By this time, Lorenzo's son Giovanni had become pope (known as Pope Leo X), and another son, Giuliano, served as the head of the pope's army. As a result, Leonardo moved to Rome, where he had his own workshop and lived in the Vatican.

During his career, Leonardo developed a technique in painting called

sfumato

, a word that comes from the Italian sfumere, which means “to tone down” or “to evaporate like smoke.”

Sfumato

is a fine shading that produces soft, almost invisible transitions between colors and tones using subtle gradations, without lines or borders, from light to dark areas. In Rome, Leonardo painted

St. John the Baptist

, which is considered the best example of

sfumato

.

For the last three years of his life, Leonardo worked in the court of Francois I, who became the king of France after Louis XII. Francois invited Leonardo to visit, and made him premier architect, engineer, and painter of his court. He was given a fine home near the palace in the Loire Valley and had no expectations placed on him but to be the king's friend. Leonardo spent his final years sketching and continuing his scientific studies and designs. In fact, his paintings of water moving and of whirlpools were used in scientific research of turbulence.

Leonardo's favorite of his own work was his most famous painting, the

Mona Lisa

. Completed in 1506, it is the smallest of his paintingsâonly thirty inches by twenty-one inchesâand is oil painted on wood. Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, Leonardo's neighbor, is believed to be the model for the

Mona Lisa

, though no one is 100 percent certain. The painting is famous for many reasons: it is an excellent example of

sfumato

and of

chiaroscuro

(a contrasting of light and shadow), but it is her expression that is most discussed about the painting. In it, her slight smile seems both innocent and knowing at the same time, and her eyes seem to follow you. Leonardo kept the painting with him until his death, at which point it became the property of King Francois. Although it now hangs in the Louvre Museum in Paris, it has also been in Napoleon's possession, hidden to protect it during the Franco-Prussian War and World War II, traveled to other countries and other museums, and was even stolen in 1911 by an Italian employee of the Louvre who believed it should reside in Italy. It was returned two years later. In 1956, part of the painting was damaged when a vandal threw acid at it, and later that same year, a rock was thrown at it, resulting in the loss of a speck of pigment near the left elbow. It is now protected by bulletproof glass.

Sandro Botticelli

May 20, 1455âMay 17, 1510

S

andro Botticelli was born in Florence and became an apprentice when he was fourteen years old. He also studied under Andrea del Verrocchio, as well as the engraver Antonio del Pollaiuolo and the master painter Fra Filippo Lippi. Botticelli got his own workshop when he was twenty-five and stayed in Florence under the patronage of the Medicis and other wealthy families there. His most famous painting is

The Birth of Venus

, which he completed around 1486, and now hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is widely agreed that his model for Venus and other women in his work was Simonetta Vespucci, for whom he had an unrequited love. Simonetta died in 1476. The unmarried Botticelli asked that when he died, he be buried at her feet. His wish was carried out when he died thirty-four years later, and they are both buried in the Church of Ognissanti in Florence.

Piero della Francesca

Circa 1415âOctober 12, 1492

A

lthough Piero della Francesca became one of the most admired painters of the Italian Renaissance, very little is known about his early life or his training as an artist. He was born in the Tuscan town of Borgo Santo Sepolcro sometime around 1415. Early records indicate that he may have apprenticed with a local painter before moving to Florence around 1439 to paint frescoes for a church there. In addition to art, he was also known as a brilliant mathematician.

Throughout his life, della Francesca received commissions to paint frescoes and altarpieces in churches in Tuscany and beyond. Though many of these have been lost or destroyed, his cycle of frescoes in the basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo is considered to be not only one of his masterpieces but also one of the masterpieces of the entire Renaissance. His painting

The Baptism of Christ

is probably the most representative of his style, in particular his use of color and light, which makes his paintings appear almost bleached.

Della Francesco never lost his ties with his small hometown, always returning there after time in cities. He spent the last two years of his life there. During that time, he is believed to have abandoned painting and returned to the study of mathematics and its relationship to painting. Interestingly, although he was respected by his peers, he did not have the influence many of them did. It wasn't until the twentieth century that he was recognized as a major artist of the Italian Renaissance.