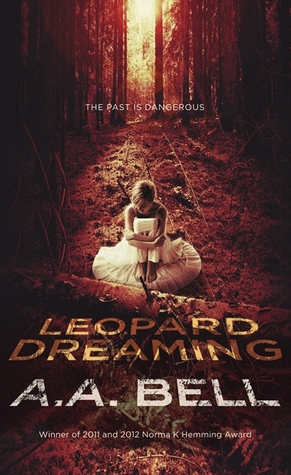

Leopard Dreaming

Authors: A.A. Bell

For my sons

whom I shall haunt forever with love

from the shadows of yester-years

For David Meshow

whose music inspires me

And with special thanks to Australia Zoo

for frisking all their kangaroos

to answer bizarre questions about Mira’s joey

M

ira paced impatiently in the foggy alcove, keeping near to the ghostly sandstone walls of the Drift Inn.

Her sunglasses stained the fog sepia, while damp shadows helped to conceal her movements beneath the balconies of the five-storey hotel and kept her out of sight from most of the yachts in the marina. Or so her bodyguard assured her.

The unusual nature of her crystalline eyes prohibited her from seeing anything real around her. She could only see their yester-ghosts; after-images of “slow light” from where they’d once been, which also meant she could only navigate safely around the things she could see if they also happened to be in the same place as they’d been. Like the power poles and buildings. Their ghostly spectres overlaid precisely in both time and space.

Even so, Mira stayed right where Lockman had left her, more or less, while he scouted the crooked alley ahead with his own form of unusual vision. In his case, binoculars that could see inside buildings using sonar waves like a bat as well as infrared.

Ambush alley. She’d already lost one good bodyguard in there, weeks ago, near the shower

block for transient sailors. The raw memory of that gunshot set her nerves on end and made her fidget, even when she commanded her legs to stay still. There were simply too many places for that killer to hide behind all the drapes and darkened windows above. Or perhaps aboard a vessel with a partial view into that alley. So much opportunity, especially for a rogue colonel with skills as a sniper. He could slice people away from her with a bullet as precisely as any surgical knife.

Yet the treacherous path served as the fastest route for hunting him now that he’d taken up the additional business of kidnapping and torturing Mira’s friends. The alley also provided the likeliest route he’d taken from the car park to the smaller piers which stretched like fingers into the neighbouring estuary — and from there, she suspected he’d taken his latest victim out into the deceptively calm waters of Moreton Bay.

Poor Matron Maddy. She’d texted the word

help

from somewhere out there. Or somebody had, using her mobile phone. Two days ago, and already emergency services had given up searching the shark-infested bay and moved on to other areas.

Eerily quiet in the alley, pre-dawn.

Mira’s sharp hearing kept her on edge, while her warm sensitive skin turned the mist into tears that seemed to cry against her cheek. Distant sobbing called to her. Imagination, she hoped, since the only disturbances she’d hoped to hear remained limited to those she could already detect. Little more than the occasional clap of a small wave against the piers, the soft click of Lockman’s binoculars switching modes from night vision to thermal imaging, or the quiet tread of his boots as he scanned through surrounding walls in search of any threatening heat signatures.

The alley cat made more noise than him as it jumped onto a rubbish bin.

Mira heard him pause inside the passage near the site of the first ambush, and wondered if he could also hear the young girl sobbing.

Probably not, since the alley took him in the opposite direction. She heard him turn north, heading deeper into the alley, while the girl kept to the south, far side of the car park. Mira heard her call the name

Lucky

several times, and imagined a kitten or puppy stuck somewhere in a drain, liable to drown soon with the incoming tide.

A ruse to draw her further from Lockman?

In the past, he would have sent a two-man team to investigate, and a second team to cover their rear, while staying glued to her side himself, but since she’d severed all ties to the military, including the rest of his unit, they had only each other for backup. Now, as civilians, she had to rely on his survival skills and instincts in order to hunt their common enemy, while he relied on her ability to see backwards through time — even though the very nature of her crystallised eyes left her blind to him … and to virtually everything else that didn’t overlay precisely in time with the yester-images she could see.

Compared to him, she felt vulnerable and useless, wandering about in the mists of time — and she’d had far more than her fill of

that

after a decade in straitjackets. All those quacks who “knew” that her visions could be nothing more than delusions. They’d tried to convince her of it too with drugs and shock treatments. Even Matron Maddy, at first.

Mira clenched her fists at her side, trying not to see the quirky young matron as the colonel’s latest victim. Tried not to see him torturing her for information about Mira’s top secret talent. The vision of her crisp uniform and spiked hair pummelled down into submission; unthinkable. Abducted from her office at Serenity, most likely, and defiant to the end, despite

the small leg and shrivelled arm which she wore like badges of honour after defeating childhood polio. As close to a mother as Mira …

She tried to stand still again, but couldn’t. The ephemeral sobbing taunted her. She couldn’t rescue Matron Maddy yet. Couldn’t even track her from the last known position of her mobile phone until after Lockman gave the all clear through the alley and out the other side to the estuary, but she needed to do something

now

.

Her skin stretched taut, like a balloon swelling, fit to explode.

‘Lucky, please,’ sobbed the girl. ‘Where are you?’

Mira’s hand reacted automatically, rising to the sidearm of her sunglasses. To anyone else, they should appear like any normal set of Ray-Bans, aside from the colour controls on each side, and the tiny battery compartment which powered her ability to change hues and intensities for each shade.

She toggled the mini-mouse and sensitive slide controls, both disguised in the pattern of a rose and vine along the sidearm, and adjusted the colour and hue of her shades from yester-month sepia to yesterday violet. At her fingertips, the controls provided an infinite range of colours to act as filters for every possible wavelength of light from past to future — violet being the nearest time period to the present that she could see without collapsing in agony. Even this close to the normal visible spectrum she needed to clamp her eyes shut briefly to help ease the eyestrain and pain of changing filters too swiftly. The sharper and faster the light, the closer to the present, and the more it felt like burning hot needles through her eyes and synapses into the back of her brain.

Fog thickened and thinned in time with the days passing. The moon chased the sun across the sky several times in a few painful seconds, and luxury

cars filed in and out from the inn’s car park — until the public car park for the marina finally emptied out, save for a few dew-covered vehicles. All in the section reserved for permanently berthed yacht owners. Mostly rusting four-wheel drives, an old Bentley and one gleaming Lamborghini Gallardo. All different colours, judging by the various hues of violet, like a monochrome movie filmed through a camera with a purple filter.

Still no sign of the ephemeral girl crying. Mira only noticed one female with a reason to cry; a pigtailed woman in a spotted bikini, who tripped and skinned her knee the previous night on the pier as she fled the biggest yacht, only to be caught against the Gallardo by her pursuer. A shirtless, tattooed young man with a fearsome temper, passionate hands and a demanding kiss. But at least the new shade gave Mira a better chance of crossing the car park to check on the crying girl without bumping into anything. Or so she hoped. Fewer things changed in a day than in a month, typically. In the last day, she noticed even fewer changes than usual. Aside from the shuffle of cars amongst different parking spaces, a sign with hotel vacancies had incremented from none to nine, and two ruts in the bitumen had widened and dug deeper into the underlying gravel.

One step off the kerb, and she caught the hem of her cotton sundress on the corner bullbar of Lockman’s Hilux.

Her

car, according to the registration papers, but whoever heard of a blind girl driving? The truck remained invisible to her, like everything else in the present. She could only see it on the rare occasions when it happened to overlay in time with its yester-spectre, like all the ghostly wharves and buildings. So it might as well be his for as long as they worked together.

Stupid!

She scolded herself. Too easy to remember which space they’d parked in at the kerb, but not how

far forward in the park. She should have afforded herself a little extra room. She did on the next try, and bumped into the rear of another invisible vehicle hanging over from the neighbouring park. A van, by the square shape of it, and pale blue, judging by the cool energy of the colour she could detect through the span of her hypersensitive fingertips. Like her hearing, taste and smell, her sense of touch had also developed in the last decade since she’d lost the last of her normal sight as a twelve-year-old.

Her fierce drive for independence kept her going unaided, even when she could have snapped a branch from a sapling in a nearby garden to use as a walking stick for fending off tripping hazards. But after ten years in captivity, she much preferred to appear clumsy than blind, for as long as the choice remained hers.

A crying child seemed unlikely to notice or care anyway. Couldn’t be older than six or eight, judging by the immature pitch in her voice. And her childish lisp.

‘Where are you?’ the girl sobbed as Mira drew nearer. ‘Where are you, Lucky, you little pick-nose? Front and centre, right now!’

Passing the Gallardo, Mira ran her hand across the rear tailfin, finding it parked precisely as it had been the day before; and warm orange in colour, according to her curious fingertips, despite the apparent ghostly sheen of yester-violet.

‘No, no, no, no!’ sobbed the invisible girl. ‘You

have

to be here, Lucky! Where are you, you rotten little …’ She scuffled about, as if crawling around the driver’s front corner of the Gallardo in clothes that squeaked and rustled like thin leather or vinyl. ‘I’ll find you, Lucky or not!’

Her movements sounded heavier than an eight-year–old’s. Her language too, despite the lisp and tone. Not that Mira had much experience with guessing kids’ ages since graduating from orphanages to asylums

herself, but at best guess, she revised her estimate of the girl’s age up to an immature twelve.

‘Need help?’ Mira whispered. She kept her head low and level with the driver’s side window of the ghostly Gallardo.

The girl spun around, squealing in fright. ‘Get away from me! No pictures, no comments!’

‘What are you talking about? I don’t even own a camera.’

‘You’re not a reporter?’

‘Me?’ Mira laughed. ‘If I were I’d have to ask: what are you doing out here?’

‘That’s none of your business! Like I told the paparazzi yesterday, I didn’t have nothing to do with that kid’s death. So what if I saw him painting the toilet block once or twice? Doesn’t mean I pushed him off the roof. Maybe he was high and thought he was Superman?’

Mira shook her head, keeping her face down. ‘Honestly, I have no idea what you’re talking about.’ The only graffiti she’d seen had all been blacked over, leaving only a ghostlier than usual impression. ‘I only came over because I thought you might need some help.’

‘Help …

me

?’ The girl burst out laughing — a sad little maniacal laugh as if

nobody

could help her.

‘Have you lost a kitten or something?’

‘No!’ She laughed again. ‘What’s it to you anyway?’

‘That depends on when it went missing.’

‘Come to gloat? I told it to you straight already. You should have been here yesterday.’

‘Then maybe you

are

lucky. I can help you find it.’ From the east, a gentle breeze began to stir the damp air along the shoreline. Stirring trouble too, if Lockman returned and found her missing from the alcove. ‘It’s dangerous out here. What’s your name?’

‘Maybelline, as if the whole world doesn’t know that already.’

‘Why, are you famous for something?’

‘Duh! Read any magazine.’

Mira frowned. ‘That’s not as easy as it sounds for me. Do your parents know you’re out this early?’

‘Parents? Are you blind, lady?’

Mira recoiled from the accusation.

‘Oh, wait! You

are

blind?’ The girl laughed, hysterically. ‘What a joke! How did you expect to help me see Lucky, then?’

‘I didn’t say

see

him. I said

find

him.’

‘How? Are you psychic?’

‘Not exactly. Unless you mean extra-sensory-perception in a non-traditional, purely scientific … Listen, do you want help to get home before sunup or not?’

‘Of course, but … I mean … well … okay, I guess I am kinda desperate. But you can’t tell anybody. Not that you would if you’re blind, right? Who’d believe you?’

‘Who indeed. Now, what kind of pet is he? Or she?’

‘Not a pet. A pick,’ the girl huffed. ‘A lucky guitar pick. It’s made of jade, and inlaid with the image of a golden good luck dragon. Named Lucky in Chinese, I think. And he’s 24 carat gold, with ruby eyes.’

‘Is he yours?’

‘Are you suggesting I stole him?’

‘Hardly.’ But something in the girl’s tone warned Mira that maybe she should be more suspicious. ‘So whose pick is it?’

‘It’s my, ah … my daddy’s.’ She giggled. ‘My sugar daddy’s. Can you find it or not?’

‘That depends if you lost it here. What makes you think that you did?’

‘Because I … ah, mean … I

saw …

someone run this way with it last night, and she dropped it, somewhere around here.’

Mira heard the lies in the girl’s voice, louder than any guitar could play. She wondered about mentioning

the place on the pier where she’d seen the pigtailed woman trip and skin her knee — until she heard heavy boots headed her way, with a stride that she recognised as Lockman’s.

‘I think you’d better go,’ Mira warned her.

‘I can’t until I find it. You don’t know what hell it’s making my life, lately. Declan thinks I stole it, even if I only intended to hide it until he finally gives me some more sugar.’