Liars and Outliers (29 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

Finally, the TSA is concerned about its relative power within the government. The more funding it has, and the closer it is to the president, the better job it can do and the more likely it is to survive.

| Societal Dilemma: Implementing airplane security. | |

| Society: Society as a whole. | |

| Competing interest: Selfish interest—garner as much power and prestige as it can. | |

| Corresponding defection: Get as much money for its budget as possible. | |

| Group interest: Airplane security whose benefits exceeds the costs. | Competing interest: Self-preservation—ensure that it won't be disbanded by the government. |

| Group norm: Implement airplane security at a reasonable level. | Corresponding defection: Become an indispensable part of airplane security. |

| Competing interest: ego preservation - ensure that if there is a terrorist attack, it won't be blamed. | |

| Corresponding defection: implement a greater level of airplane security than the risk trade-off warrants. | |

| To encourage people to act in the group interest, society implements these societal pressures: Moral: We teach people to do the right thing. Reputational: Institutions that put their own survival ahead of their nominal missions aren't thought of very well. Institutional: Legislators and courts rein institutions in. Security: Auditors, inspectors, cameras, and monitoring. |

The TSA's competing interests are common in government agencies. You can see it with the police and other law-enforcement bodies. These institutions have been delegated responsibility for implementing institutional pressure on behalf of society as a whole, but because their interests are different, they end up implementing security at a greater or lesser level than society would have.

Exaggerating the threat, and oversecuring—or at least overspending—as a result of that exaggeration, is by far the most common outcome. The TSA, for instance, would never suggest returning airport security to pre-9/11 levels and giving the rest of its budget back so it could be spent on broader anti-terrorism measures that might make more sense, such as intelligence, investigation, and emergency response. It's a solution that goes against the interests of the TSA as an institution.

This dynamic is hardly limited to government institutions. For example, corporate security officers exhibit the same behavior. In Chapter 10, I described the problem of corporate travel expenses, and explained that many large corporations implement societal pressures to ensure employee compliance. This generally involves approval—either beforehand for things like airfare and hotels, or after-the-fact verification of receipts and auditing—of travel expenses. To do this, the corporation delegates approval authority to some department or group of people, which determines what sort of pressures to implement. That group's motivation becomes some combination of keeping corporate travel expenses down and justifying its own existence as a department within the corporation, so it overspends.

Recall the professional athletes engaging in an arms race with drug testers. It might be in the athletes' group interest for the sport of cycling to be drug-free, but the actual implementation of that ideal is in the hands of the sport's regulatory bodies. The World Anti-Doping Agency takes the attitude of “ban everything, the hell with the consequences.” It might better serve the athletes if the agency took more time and spent more money developing more accurate tests, was more transparent about its testing methodology, and had a straightforward redress procedure for athletes falsely accused—but it's not motivated to make that risk trade-off. And as long as it's in charge, it's going to do things its way.

Enforcing institutions have a number of other competing interests resulting from delegation. A common one has to do with how the enforcing institutions are measured and judged. We delegate to the police the enforcement of law, but individual policemen get reviewed and promoted based on their arrest and conviction rate. This can result in a variety of policing problems, including a police department's willingness to pursue an innocent person if it believes it can get a conviction, and pushing for an easy conviction on a lesser charge rather than a harder conviction on a more accurate charge.

There's one competing interest that's unique to enforcing institutions, and that's the interest of the group the institution is supposed to watch over. If a government agency exists only because of the industry, then it is in its self-preservation interest to keep that industry flourishing. And unless there's some other career path, pretty much everyone with the expertise necessary to become a regulator will be either a former or future employee of the industry, with the obvious implicit and explicit conflicts. As a result, there is a tendency for institutions delegated with regulating a particular industry to start advocating the commercial and special interests of that industry. This is known as

regulatory capture

, and there are many examples both in the U.S. and in other countries. U.S. examples include:

- The Minerals Management Service, whose former managers saw nothing wrong with

steering contracts to

ex-colleagues embarking on start-up private ventures, and having sexual relationships with and accepting gifts from oil and gas industry employees. In fact, the MMS was broken up in 2010 because this cozy relationship was blamed in part for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. - The

Federal Aviation Administration

, whose managers' willingness to overlook or delay action on crucial safety problems contributed to the 1996 crash of a ValuJet Airlines DC-9 in the Everglades, and the 2011 sudden in-flight failure of a section of fuselage on a Southwest Airlines 737. - The

Securities and Exchange

Commission, whose lawyers routinely move to government employment from the banking industry, and back after their term of service is over. One of the effects of this revolving door was a poorly regulated banking industry that caused the financial crisis of 2008.

One way to think about all this is as a battle between diffuse interests and concentrated interests. If you assume that specific regulations are a trade-off between costs and benefits, a regulatory institution will attempt to strike a balance. On one side is the industry, which is both powerful and very motivated to influence the regulators. On the other side is everyone else, each of whom has many different concerns as they go about their day and none of whom are particularly motivated to try to influence the regulators. In this way, even if the interests of society as a whole are greater than the interests of the industry, they're not as well-represented because they're so diffuse. And to the extent that the institution is society's agent for implementing societal pressures, this becomes a colossal failure of societal interest. Moreover, each level of delegation introduces new competing interests, like a horribly conflicted game of telephone.

Institutions have power, and with that power comes the ability to defect. Throughout history, governments have acted in the self-interest of their rulers and not in the best interest of society. They can establish social norms and enforce those norms through laws and punishment. They can do this with or without the support of the people.

But there's a new type of potentially defecting institution, one that's made possible by the information age: corporations acting in the role of institutions. This can happen whenever public infrastructure moves into private hands. With the rise of the Internet as a communications system, and social networking sites in particular, corporations have become the designers, controllers, and arbiters of our social infrastructure. As such, they are assuming the role of institutions even though they really aren't. We talked in Chapter 10 about how combining reputational pressure with security systems gives defectors new avenues for bypassing societal pressures, like posting fake reviews on Yelp. Another effect is that the corporation that designs and owns the security mechanisms can facilitate defection at a much higher level.

Like an autocratic government, the company can set societal norms, determine what it means to cooperate, and enforce cooperation through the options on its site. It can take away legal and socially acceptable rights simply by not allowing them: think of how publishers have eroded fair use rights for music by not enabling copying options on digital players. And when the users of the site are not customers of the corporation, the competing interests are even stronger.

Take Facebook as an example. Facebook gets to decide what privacy options users have. It can allow users to keep certain things private if they want, and it can deny users the ability to keep other things private. It can grant users the ability to fine-tune their privacy settings, or it can only give users all-or-nothing options. It can make certain options easy to find and easy to use, and can make other options hard to find and even harder to use. And it will do or not do all of these things based on its business model of selling user information to other companies for marketing purposes. Facebook is the institution implicitly delegated by its users to implement societal pressures, but because it is a for-profit corporation and not a true agent for its users, it defects from society and acts in its own self-interest, effectively reversing the principal–agent relationship. Of course, users can refuse to participate in Facebook. But as Facebook and other social networking sites become embedded in our culture and our socialization, opting out becomes less of a realistic option. As long as the users either have no choice or don't care, it can act against its users' interests with impunity.

It's not easy to implement societal pressures against institutions that put their competing interests ahead of the group interest. Like any other organization, institutions don't respond to moral pressure in the same way individuals do. They can become impervious to reputational pressure. Since people are often forced to interact with institutions, it often doesn't matter what people think of them. Yes, in a democracy, people can vote for legislators who will better delegate societal pressures to these institutions, but this is a slow and indirect process. You could decide to not use a credit card or a cell phone and therefore not do business with the companies that provide them, but often that's not a realistic alternative.

Sometimes the authorities are just plain unwilling to punish defecting institutions. No one in the U.S. government is interested in taking the National Security Agency to task for

illegally spying

on American citizens (spy agencies make bad enemies). Or in punishing anyone for

authorizing the torture

of—often innocent—terrorist suspects. Similarly, there's little questioning legislatively about President Obama's self-claimed

right to assassinate

Americans abroad without due process.

The most effective societal pressures against institutions are themselves institutional. An example is the lawsuit I talked about at the start of this chapter. EPIC sued the TSA over full-body scanners, claiming the agency didn't even follow its own rules when it fielded the devices. And while the

court rejected EPIC's

Fourth Amendment arguments and allowed the TSA to keep screening, it ordered the TSA to conduct notice-and-comment rulemaking. Not a complete victory by any means, but a partial one.

And there are many examples of government institutions being reined in by the court system. In the U.S., this includes judicial review, desegregating schools, legalizing abortion, striking down laws prohibiting interracial and now same-sex couples from marrying, establishing judicial oversight for wiretapping, and punishing trust fund mismanagement at the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

What's important here is accountability. It is important that these mechanisms are seen publicly, and that people are held accountable. If we're going to keep government from overstepping its bounds, it will be through separation of powers: checks and balances. But it's not just government that needs to be watched; it's corporations, non-government institutions, and individuals. It's everyone's responsibility to keep everyone else in check.

Part IV

Conclusions

Chapter 15

How Societal Pressures Fail

Let's start our discussion of societal pressure failures with an example: taxes. Paying taxes is a classic free-rider problem; if almost everyone cooperates by paying taxes, defectors get all the benefits of whatever those taxes are paying for without having to suffer the financial penalties of actually paying.

1

There are laws and enforcement, but at least in the U.S., with the exception of payroll taxes, income tax is almost entirely enforced by voluntary compliance. It's not just a financial risk trade-off; there are two pieces of moral pressure at work here:

people paying taxes

because it's the right thing to do, and people paying taxes because it's the law and following the law is the right thing to do.

Still, there's

a lot of fraud

in the U.S. According to the IRS, in 2001—the most recent year I could find comprehensive numbers for—the difference between total taxes owed and total taxes paid was $345 billion; about 19% of the total taxes due. A

third-party estimate

from 2008 tax returns also showed a 19% tax gap. Note that this gap is in the percentage of money owed, not the percentage of cheaters. By one estimate, 25% of individuals admit to

cheating on their taxes

. On the other hand, a single corporation avoiding billions in taxes costs taxpayers vastly more money than many thousands of waiters lying about their tip income.

There are many

reasons people cheat

on their taxes, and they all point to failures of societal pressure. First, there is

very little enforcement

. In 2007, for example, the

IRS examined less

than 1% of the 179 million tax returns filed, initiated criminal prosecutions in only 4,211 cases, and obtained indictments in only 2,322 cases.

Corporate audits are down

, too, both in number and thoroughness. And while there's debate about whether

increasing the penalties

against tax evaders increases compliance, we do know that increasing the number of audits

increases compliance

and—of course—collects more of the taxes owed. Aside from low-level cheating that can be easily detected by computer matching, cheating on your taxes is easy and you're not likely to get caught.

Second, it's profitable

. These days, if you're making a 5% return on your investments, you're doing really well. With the top federal tax rate at 35%, the money you can save by cheating is a pretty strong motivation. These are not people who can't afford to pay taxes; the typical tax cheat is a male under 50 in a high tax bracket and with a complex return. (Poorer users, with all their income covered by payroll taxes, have less opportunity to cheat.) The current situation creates an incentive to cheat.

Third, people think that lots of other people do it. Remember the Bad Apple Effect? There's a 1998 survey showing people believe that 38% of their fellow taxpayers are

failing to declare

all their income and listing false deductions. And the high-profile tax cheats that make the news reinforce this belief.

And fourth, recent political rhetoric has

demonized taxes

. Cries that taxation equals theft, that the tax system is unfair, and that the government just wastes any money you give it gives people a different morality, which they use to justify underpayment. This weakens the original moral pressure to pay up.

All of

these reasons interact

with each other. One study looked at tax evasion over about 50 years, and found that it increases with income tax rates, the unemployment rate, and public dissatisfaction with government. Another

blamed income inequality

.

Despite all of this, the U.S. government collects 81% of all taxes owed. That's actually pretty impressive compared to some countries.

There's another aspect to this. In addition to illegal tax evasion, there's what's called tax avoidance: technically legal measures to reduce taxes that run contrary to the tax code's policy goals. We discussed tax loopholes at length in Chapter 9. There are a lot of creative companies figuring out ways to follow the letter of the tax law while completely ignoring the spirit. This is how companies can make billions in profits yet pay little in taxes. And make no mistake, industries, professions, and groups of wealthy people deliberately manipulate the legislative system by lobbying Congress to get special tax exemptions to benefit themselves. One example is the

carried-interest tax

loophole: the taxation of private equity fund and hedge fund manager compensation at the 15% long-term capital gains tax rate rather than as regular income. Another is the

investment tax credit

, intended to help building contractors, that people used to subsidize expensive SUVs. There's also tax flight—companies moving profits out of the country to reduce taxes.

Estimates of lost federal revenue due to legal tax avoidance and tax flight are about $1 trillion. Adding tax evasion, the total amount of lost revenue is $1.5 trillion, or 41% of total taxes that should be collected. Collecting these taxes would more than eliminate the federal deficit.

Okay, so maybe that's not so good.

There are a lot of societal pressure failures in all of this. Morals differ: people tend to perceive tax evasion negatively, tax flight—companies moving profits out of the country to reduce taxes—neutrally, and tax avoidance positively: it's legal and clever. Even so, a reasonable case can be made that tax avoidance is just as immoral as tax evasion. The reputational effects of being a public tax cheat are few, and can be positive towards people who are clever enough to find legal loopholes. Institutional pressure depends on enforcement, which is spotty. Security systems are ineffective against the more complex fraud.

Remember the goal of societal pressures. We want a high level of trust in society. Society is too complex for the intimate form of trust—we have to interact with too many people to know all of their intentions—so we're settling for cooperation and compliance. In order for people to cooperate, they need to believe that almost everyone else will cooperate too. We solve this chicken-and-egg problem with societal pressures. By inducing people to comply with social norms, we naturally raise the level of trust and induce more people to cooperate. This is the positive feedback loop we're trying to get.

Societal pressures operate on society as a whole. They don't enforce cooperation in all people in all circumstances. Instead, they induce an overall level of cooperation. Returning to the immune system analogy, no defense works in all circumstances. As long as the system of societal pressures protects society as a whole, individual harm isn't a concern. It's not a failure of societal pressure if someone trusts too much and gets harmed because of it, or trusts too little and functions poorly in society as a result. What does matter is that the overall scope of defection is low enough that the overall level of trust is high enough for society to survive and hopefully thrive.

This sounds callous, but it's true. In the U.S., we tolerate 16,000–18,000 murders a year, and a tax gap of $1.5 trillion. By any of the mechanisms discussed in Chapter 14, society gets to decide what level of defection we're willing to tolerate, and those numbers have fluctuated over the years. These are only failures of societal pressure if society thinks these numbers are either too high or too low.

In Chapter 6, I talked about societal pressures as a series of knobs. Depending on the particular societal dilemma, society determines the scope of defection it can tolerate and then—if it's all working properly—dials the societal pressure knobs to achieve that balance. Recall the Hawk-Dove game from Chapter 3; a variety of different initial parameters result in stable societies. If we want less murder, we increase societal pressures. If that ends up being too expensive and we can tolerate a higher murder rate, we decrease societal pressures.

That metaphor is basically correct, but it's simplistic. We don't have that level of accuracy when we implement societal pressures. In the real world, the knobs are poorly marked and badly calibrated, there's a delay after you turn one of them before you notice any effects, and there's so much else going on that it's hard to figure out what the effect actually is. Think of a bathtub with leaky unmarked faucets, where you can't directly see the water coming out of the spout…outside, in the rain. You sit in the tub, oscillating back and forth between the water being too hot and too cold, and eventually you give up and take an uncomfortable bath. That's a more accurate metaphor for the degree of control we have with societal pressures.

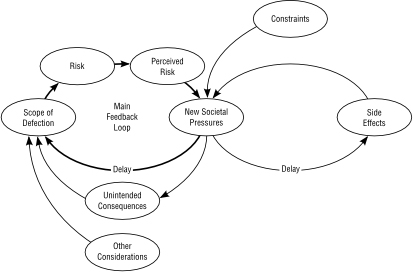

Figure 13

tries to capture all of this.

2

On the left is the main feedback loop, between new societal pressures and the scope of defection. New societal pressures cause a change in the scope of defections, which causes a change in both risk and perceived risk. Then, the new perceived risk causes calls for changes in societal pressures.

Notice the delay between implementing new societal pressures and seeing corresponding changes in the scope of defection. The delay comes from several sources. One, moral and reputational pressures are inherently slow. Anything that affects risk trade-offs through a deterrence effect will require time before you see any effects from it. Depending on the form of government, new institutional pressures can also be slow. So can security systems: time to procure, time to implement, time before they're used effectively.

For example, the

first people arrested

for writing computer viruses in the pre-Internet era went unpunished because there weren't any applicable laws to charge them with. Internet e-mail was not designed to provide sender authentication; the result was the emergence of spam, a problem we're still trying to solve today. And in the U.S., the FBI regularly complains that the

laws regulating surveillance

aren't keeping up with the rapidly changing pace of communications technology.

Two, it can take time for a societal pressure change to propagate through society. All of this makes it harder to fine-tune the system, because you don't know when you're seeing the full effects of the societal pressures currently in place. And three, it takes time to measure any changes in the scope of defection. Sometimes you need months or even years of statistical data before you know if things are getting better or worse.

The feedback is also inexact. To use a communications theory term, it's noisy. Often you can't know the exact effects of your societal pressures because there are so many other things affecting the scope of defection at the same time; in

Figure 13

, those are the “other considerations.” For instance, in the late 20th century, the drop in the U.S. crime rate has been linked to the

legalization of abortion

20 years previously. Additionally, society's perceptions of risks are hard to quantify, and contain a cultural component. I'll talk more about this later in the chapter.

Figure 13:

Societal Pressure's Feedback Loops

A related feedback loop, shown as the lower loop on the left in

Figure 13

, is also important. These are the

unintended consequences

of societal pressures that often directly affect the scope of defection. A large-scale example would be the effects on crime of Prohibition, or of incarcerating 16–25% of young black men in the U.S. A smaller-scale example is that hiring guards to prevent shoplifting may end up

increasing shoplifting

, because regular employees now believe that it's someone else's job to police the store and not theirs. Electronic sensor tags have a similar effect.

Security systems are complex, and will invariably have side effects on society. This is shown as the loop on the right side of

Figure 13

. For example, the U.S. incarceration rate has much broader social effects than simply locking up criminals. Prohibition did, too. A simple side effect is that some societal pressures, mostly security systems, cost money. More subtle side effects are

fewer bicycle riders

as a result of helmet laws, a

chilling effect on

computer-security research due to laws designed to prevent the digital copying of music and movies, and

increased violence

as a result of drug enforcement.