Liars and Outliers (4 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

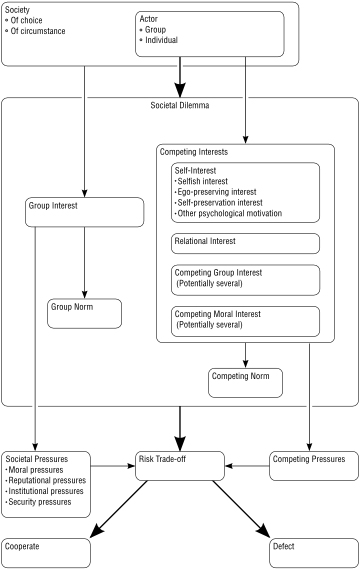

Every person in a society potentially has one or more

competing interests

that conflict with the group interest, and

competing norms

that conflict with the group norm. Someone in that we-don't-steal society might really want to steal. He might be starving, and need to steal food to survive. He just might want other people's stuff. These are examples of

self-interest.

He might have some competing

relational interest.

He might be a member of a criminal gang, and need to steal to prove his loyalty to the group; here, the competing interest might be the group interest of another group. Or he might want to steal for some higher moral reason: a competing

moral interest

—the Robin Hood archetype, for example.

A

societal dilemma

is the choice every actor has to make between group interest and his or her competing interests. It's the choice we make when we decide whether or not to follow the group norm. Those who do

cooperate

, and those who do not

defect

. Those are both loaded terms, but I mean them to refer only to the action as a result of the dilemma.

Defectors

—the liars and outliers of the book's title—are the people within a group who don't go along with the norms of that group. The term isn't defined according to any absolute morals, but instead in opposition to whatever the group interest and the group norm is. Defectors steal in a society that has declared that stealing is wrong, but they also help slaves escape in a society where tolerating slavery is the norm. Defectors change as society changes; defection is in the eye of the beholder. Or, more specifically, it is in the eyes of everyone else. Someone who was a defector under the former East German government was no longer in that group after the fall of the Berlin Wall. But those who followed the societal norms of East Germany, like the Stasi, were—all of a sudden—viewed as defectors within the new united Germany.

Figure 1:

The Terms Used in the Book, and Their Relationships

Criminals are defectors, obviously, but that answer is too facile. Everyone defects at least some of the time. It's both dynamic and situational. People can cooperate about some things and defect about others. People can cooperate with one group they're in and defect from another. People can cooperate today and defect tomorrow, or cooperate when they're thinking clearly and defect when they're reacting in a panic. People can cooperate when their needs are cared for, and defect when they're starving.

When four black North Carolina college students staged a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter inside a Woolworth's five-and-dime store in Greensboro, in 1960, they were criminals. So are women who drive cars in Saudi Arabia. Or homosexuals in Iran. Or the 2011 protesters in Egypt, who sought to end their country's political regime. Conversely, child brides in Pakistan are not criminalized and neither are their parents, even though in some cases they marry off five-year-old girls. The Nicaraguan rebels who fought the Sandinistas were criminals, terrorists, insurgents, or freedom fighters, depending on which side you supported and how you viewed the conflict. Pot smokers and dealers in the U.S. are officially criminals, but in the Netherlands those offenses are ignored by the police. Those who share copyrighted movies and music are breaking the law, even if they have moral justifications for their actions.

Defecting doesn't necessarily mean breaking government-imposed laws. An orthodox Jew who eats a ham and cheese sandwich is violating the rules of his religion. A Mafioso who snitches on his colleagues is violating

omertà

, the code of silence. A relief worker who indulges in a long, hot shower after a tiring journey, and thereby depletes an entire village's hot water supply, unwittingly puts his own self-interest ahead of the interest of the people he intends to help.

What we're concerned with is the overall

scope of defection.

I mean this term to be general, comprising the number of defectors, the rate of their defection, the frequency of their defection, and the intensity (the amount of damage) of their defection. Just as we're interested in the general level of trust within the group, we're interested in the general scope of defection within the group.

Societal pressures

are how society ensures that people follow the group norms, as opposed to some competing norms. The term is meant to encompass everything society does to protect itself: both from fellow members of society, and non-societal members who live within and amongst the society. More generally, it's how society enforces intra-group trust.

The terms

attacker

and

defender

are pretty obvious. The predator is the attacker, the prey is the defender. It's all intertwined, and sometimes these terms can get a bit muddy. Watch a martial arts match, and you'll see each person defending against his opponent's attacks while at the same time hoping his own attacks get around his opponent's defenses. In war, both sides attack and defend at the tactical level, even though one side might be attacking and the other defending at the political level. These terms are value-neutral. Attackers can be criminals trying to break into a home, superheroes raiding a criminal mastermind's stronghold, or cancer cells metastasizing their way through a hapless human host. Defenders can be a family protecting its home from invasion, the criminal mastermind protecting his lair from the superheroes, or a posse of leukocytes engulfing opportunistic pathogens they encounter.

These definitions are important to remember as you read this book. It's easy for us to bring our own emotional baggage into discussions about security, but most of the time we're just trying to understand the underlying mechanisms at play, and those mechanisms are the same, regardless of the underlying moral context.

Sometimes we need the dispassionate lens of history to judge famous defectors like Oliver North, Oskar Schindler, and Vladimir Lenin.

Part I

The Science of Trust

Chapter 2

A Natural History of Security

Our exploration of trust is going to start and end with security, because security is what you need when you don't have any trust and—as we'll see—security is ultimately how we induce trust in society. It's what brings risk down to tolerable levels, allowing trust to fill in the remaining gaps.

You can learn a lot about security from watching the natural world.

- Lions seeking to protect their turf will raise their voices in a “

territorial chorus

,” their cooperation reducing the risk of encroachment by other predators for the local food supply. - When

hornworms

start eating a particular species of sagebrush, the plant responds by emitting a molecule that warns any wild tobacco plants growing nearby that hornworms are around. In response, the tobacco plants deploy chemical defenses that repel the hornworms, to the benefit of both plants. - Some types of

plasmids secrete

a toxin that kills the bacteria that carry them. Luckily for the bacteria, the plasmids also emit an antidote; and as long as a plasmid secretes both, the host bacterium survives. But if the plasmid dies, the antidote decays faster than the toxin, and the bacterium dies. This acts as an insurance policy for the plasmids, ensuring that bacteria don't evolve ways to kill them.

In the beginning of life on this planet, some 3.8 billion years ago, an organism's only job was to reproduce. That meant growing, and growing required energy.

Heat and light

were the obvious sources—photosynthesis appeared 3 billion years ago; chemosynthesis is at least a half a billion years older than that—but consuming the other living things floating around in the primordial ocean worked just as well. So life discovered predation.

We don't know what that

first animal predator

was, but it was likely a simple marine organism somewhere between 500 million and 550 million years ago. Initially, the only defense a species had against being eaten was to have so many individuals floating around the primordial seas that enough individuals were left to reproduce, so that the constant attrition didn't matter. But then life realized it might be able to avoid being eaten. So it evolved defenses. And predators evolved better ways to catch and eat.

Thus security was born, the planet's fourth oldest activity after eating, eliminating, and reproducing.

Okay, that's a pretty gross simplification, and it would get me booted out of any evolutionary biology class. When talking about evolution and natural selection, it's easy to say that organisms make explicit decisions about their genetic future. They don't. There's nothing purposeful or teleological about the evolutionary process, and I shouldn't anthropomorphize it. Species don't realize anything. They don't discover anything, either. They don't decide to evolve, or try genetic options. It's tempting to talk about evolution as if there's some outside intelligence directing it. We say “prehistoric lungfish first learned how to breathe air,” or “monarch butterflies learned to store plant toxins in their bodies to make themselves taste bad to predators,” but it doesn't work that way. Random mutation provides the material upon which natural selection acts. It is through this process that individuals of a species change subtly from their parents, effectively “trying out” new features. Those innovations that turn out to be beneficial—air breathing—give the individuals a competitive advantage and might potentially propagate through the species (there's still a lot of randomness in this process). Those that turn out to be detrimental—the overwhelming majority of them—kill or otherwise disadvantage the individual and die out.

By “beneficial,” I mean something very specific: increasing an organism's ability to survive long enough to successfully pass its genes on to future generations. Or, to use Richard Dawkins's perspective from

The Selfish Gene

, genes that helped their host individuals—or other individuals with that gene—successfully reproduce tended to persist in higher numbers in populations.

If we were designing a life form, as we might do in a computer game, we would try to figure out what sort of security it needed and give it abilities accordingly. Real-world species don't have that luxury. Instead, they try new attributes randomly. So instead of an external designer optimizing a species' abilities based on its needs, evolution randomly walks through the solution space and stops at the first solution that works—even if just barely. Then it climbs upwards in the fitness landscape until it reaches a local optimum. You get a lot of weird security that way.

You get teeth, claws, group dispersing behavior, feigning injury and playing dead, hunting in packs, defending in groups (flocking and schooling and living in herds), setting sentinels, digging burrows, flying, mimicry by both predators and prey, alarm calls, shells, intelligence, noxious odors, tool using (both offensive and defensive),

1

planning (again, both offensive and defensive), and a whole lot more.

2

And this is just in largish animals; we haven't even listed the security solutions insects have come up with. Or plants. Or microbes.

It has been convincingly argued that one of the reasons sexual reproduction evolved about 1.2 billion years ago was to

defend against

biological parasites. The argument is subtle. Basically, parasites reproduce so quickly that they overwhelm any individual host defense. The value of DNA recombination, which is what you get in sexual reproduction, is that it continuously rearranges a species' defenses so parasites can't get the upper hand. For this reason, a member of a species that reproduces sexually is much more likely to survive than a species that clones itself asexually—even though such a species will pass twice as many of its genes to its offspring as a sexually reproducing species would.

Life evolved two other methods of defending itself against parasites. One is to grow and divide quickly, something that both bacteria and just-fertilized mammalian embryos do. The other is to have an immune system. Evolutionarily, this is a relatively new development; it first appeared in

jawed fish

about 300 million years ago.

3

A surprising number of evolutionary adaptations are related to security. Take vision, for example. Most animals are more adept at spotting movement than picking out details of stationary objects; it's called the

orienting response

.

4

That's because things that move may be predators that attack, or prey that needs to be attacked. The human visual system is

particularly good

at spotting animals.

5

The human ability, unique on the planet, to

throw things

long distances is another security adaptation. Related is what's called the

size-weight misperception

: the illusion that easier-to-throw rocks are perceived to be lighter than they are. It's related to our ability to choose good projectiles.

Similar stories

could be told about many human attributes.

6

The predator/prey relationship isn't the only pressure that drives evolution. As soon as there was competition for resources, organisms had to develop security to defend their own resources and attack the resources of others. Whether it's plants competing with each other for access to the sun, predators fighting over hunting territory, or animals competing for potential mates, organisms had to develop security against others of the same species. And again, evolution resulted in all sorts of

weird security

. And it works amazingly well.

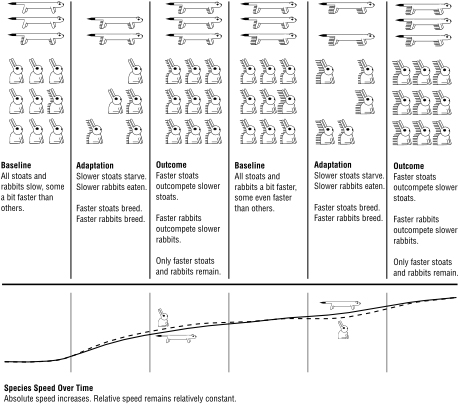

Security on Earth went on more or less like this for 500 million years. It's a continual arms race. A rabbit that can run away at 30 miles per hour—in short bursts, of course—is at an evolutionary advantage when the weasels and stoats can only run 28 mph, but at an evolutionary disadvantage once predators can run 32 mph.

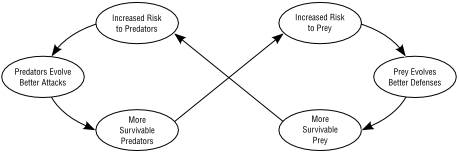

Figure 2:

The Red Queen Effect in Action

It's different when the evolutionary advantage is against nature. A polar bear has thick fur because it's cold in the Arctic. And it's thick to a point, because the Arctic doesn't get colder in response to the polar bear's changes. But that same polar bear has fur that appears white so as to better sneak up on seals. But a better camouflaged polar bear means that only more wary seals survive and reproduce, which means that the polar bears need to be even better at camouflage to eat, which means that the seals need to be more wary, and on and on and on up to some physical upper limit on camouflage and wariness.

This only-relative evolutionary arms race is known as the

Red Queen Effect

, after Lewis Carroll's race in

Through the Looking-Glass

: “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” Predators develop all sorts of new tricks to catch prey, and prey develop all sorts of new tricks to evade predators. The prey get more poisonous, so their predators get more poison-resistant, so the prey get even more poisonous. A species has to

continuously improve

just to survive, and any species that can't keep up—or bumps up against physiological or environmental constraints—becomes extinct.

Figure 3:

The Red Queen Effect Feedback Loop

Along with becoming faster, more poisonous, and bitier, some organisms became smarter. At first, a little smarts went a long way. Intelligence allows individuals to adapt their behaviors, moment by moment, to suit their environment and circumstances. It allows them to remember the past and learn from experience. It lets them be individually adaptive. No one has a date, but vertebrates first appeared about 525 million years ago—and continued to improve on various branches of the tree of life: mammals (215 million years ago), birds (75 million years ago), primates (60 million years ago), the genus

Homo

(2.5 million years ago), and then humans (somewhere between 200,000 and 450,000 years ago, depending on whose evidence you believe). When it comes to security, as with so many things, humans changed everything.

Let's pause for a second. This isn't a book about animal intelligence, and I don't want to start an argument about which animals can be considered intelligent, or what about human intelligence is unique, or even how to define the word “intelligence.” It's definitely a fascinating subject, and we can learn a lot about our own intelligence by studying the intelligence of

other animals

. Even my neat intelligence progression from the previous paragraph might be wrong: flatworms can be trained, and some cephalopods are surprisingly smart. But those topics aren't really central to this book, so I'm going to elide them. For my purposes, it's enough to say that there is a uniquely human intelligence.

7

And humans take their intelligence seriously. The brain only represents 3% of total body mass, but uses 20% of the body's total blood supply and 25% of its oxygen. And—unlike other primates, even—we'll

supply our brains

with blood and oxygen at the expense of other body parts.

One of the things intelligence makes possible is

cultural evolution

. Instead of needing to wait for genetic changes, humans are able to improve their survivability through the direct transmission of skills and ideas. These memes can be taught from generation to generation, with the more survivable ideas propagating and the bad ones dying out. Humans are not the only species that teaches its young, but humans have taken this to a new level.

8

This caused a flowering of security ideas: deception and concealment; weapons, armor, and shields; coordinated attack and defense tactics; locks and their continuous improvement over the centuries; gunpowder, explosives, guns, cruise missiles, and everything else that goes “bang” or “boom”; paid security guards and soldiers and policemen; professional criminals; forensic databases of fingerprints, tire tracks, shoe prints, and DNA samples; and so on.

It's not just intelligence that makes humans different. One of the things that's unique about humans is the extent of our socialization. Yes, there are other social species: other primates, most mammals and some birds.

9

But humans have taken sociality to a completely different level. And with that socialization came all sorts of new security considerations: concern for an ever-widening group of individuals, concern about potential deception and the need to detect it, concern about one's own and others' reputations, concern about rival groups of attackers and the corresponding need to develop groups of defenders, recognition of the need to take preemptive security measures against potential attacks, and after-the-fact responses to already-occurred attacks for the purpose of deterring others in the future.

10