Liberalism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) (5 page)

Read Liberalism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) Online

Authors: Michael Freeden

If, however, there are many liberalisms, they may best be identified through historical and ideological analysis rather than through the philosophical postulation of an ideal-type, which is by its very nature unitary. The diversity of those liberalisms exists on two levels. The first, as already illustrated, pertains to the level of geographical and cultural differences. Even the most universal of liberalisms, were there indeed such a thing, would have to pass through the cultural filters of the society in question. As with cooking, local and regional ingredients and flavours have a considerable impact on the liberal cuisine. In commercial and financial centres, the entrepreneurial attributes that liberalism encourages come to the fore. In societies that have undergone secularization, the belief in human decency rather than God-willed natural rights underpins the liberal sensitivity to, and respect for, others. In societies that are multi-cultural, the constitutional rights to a measure of self-determination of various groups within that society—ethnic, geographic, religious, or gender-based—are prominent in liberal discourse. All those nuances emerge as a consequence of our awareness of where we stand in relation to time and space.

The morphology of liberalism

The study of ideologies also alerts us to another kind of multiplicity. Ideologies, liberalism included, clump ideas together in certain combinations that have a unique profile, a distinct morphological pattern. They arrange political concepts such as liberty, justice, equality, or rights in clusters. The clusters at the liberal core will be those that appear in all the known versions of liberalism and without which it would be unrecognizable. Anticipating the discussion in

Chapter 4

, we can arrive at a provisional statement based on the analysis of what liberals have actually said and written (see

Box 2

).

Those seven core elements are the nucleus around which all liberalisms revolve. However, the differences among liberalisms then begin to make themselves felt. First, the proportionate weight accorded to each of these concepts within the family of liberalisms may differ. For instance, some liberalisms might recognize the role of emotion and slightly demote rationality; others might play down the innate sociability of people; others again might prefer a strong form of individuality over a pronounced concern for the general interest. The basic ingredients of the liberal cocktail may be similar, but the quantity of each ingredient may change.

Second, every one of those concepts carries more than one meaning. To give an example, liberty could refer to the absence of external constraints that permits self-determination. But it could also relate to the possibility of cultivating one’s personal potential in order to facilitate self-development. It could further signify the emancipation of a group or nation due to the combined efforts of their members to rid themselves of external control, or a free-for-all among unrestrained individuals that results in anarchy or social chaos. Because all political concepts have many conceptions, there is endless contestation over which is the most appropriate to a given set of circumstances. One of the key roles that ideologies perform is to decide which conception to endorse within each of the concepts they contain. In other words, they decontest the essential contestability of those concepts by conferring a certainty on one of those meanings, however questionable and illusory it might be. Different cultures across the globe will rule some meanings in and others out. Nor is the choice of one meaning necessarily due to deliberate deception. It may be sincerely held or unconsciously assumed. Ultimately there is no correct formula, no totally objective view, from which to ascertain once and for all what exactly liberalism ought to incorporate and signify. Yet in living our lives we need to create certainties, however fleeting or erroneous, because without them we cannot make sense of the world or reach decisions when confronted with conflicting choices. Liberalism supplies one of the numerous maps available as people attempt to navigate through their social and political environments, and it is a map that has guided many individuals, governments, and societies. We will re-examine this conceptual approach to liberalism in

Chapter 4

.

Box 2 The conceptual morphology of liberalism

Liberalism is an ideology that contains seven political concepts that interact at its core: liberty, rationality, individuality, progress, sociability, the general interest, and limited and accountable power.

Liberal institutions

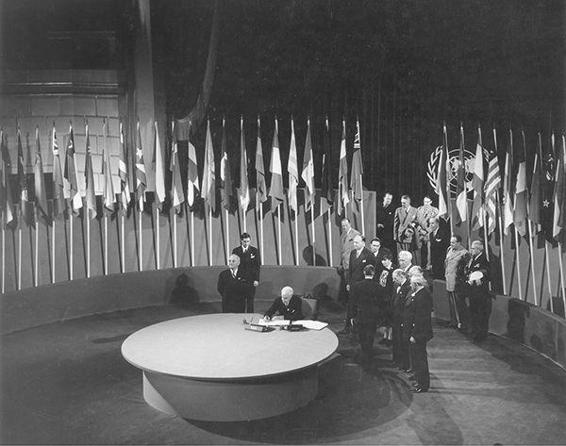

Liberalism is evidently also associated with political movements, organizations, and parties. Most countries that practise forms of liberal democracy, in Europe or elsewhere, have a liberal party either in name or in programme. Many institutions, not least on the international stage, have seen themselves as purveyors of liberal ideas in the general sense. The United Nations Charter of 1945 emphasizes the pursuit of peace, justice, equal rights, and non-discrimination—principles straight out of the liberal lexicon (

Figure 2

). But here a gap opens up between the ideological and institutional manifestations of liberalism. Liberal ideologies are generally speaking broader than the parties and groupings that operate under that name. J.M. Keynes memorably wrote, ‘Possibly the Liberal Party cannot serve the State in any better way than by supplying Conservative Governments with Cabinets, and Labour Governments with ideas.’ But

pace

Keynes, the Liberal party in Britain, or the Liberal Democrats as they are now called, have fed off wider ranging liberal thinking over the years and political parties are rarely a source of ideological innovation. Indeed, some parties flaunting the label ‘liberal’ are far from liberal, an example being the Liberal Democratic party in Japan, which is a centre-right conservative party. Liberal thinkers and ideas generally emerge from debates among intellectuals, from the campaigning zeal of social reformers and journalists—including newspapers aligned with liberal causes—and from dedicated pressure groups and, more recently, think tanks and blogs. But due to their public profile, political parties are often taken by public opinion to be the representatives of the ideologies they reference. During the 19th century, Liberal parties were in their heyday and their influence over the ideological agenda was at its highest, though that power has since declined. Parties are therefore only a partially reliable indicator of the ideologies they claim to stand for. They also only seldom contain liberal philosophers working at a specialized and abstract level of articulation, precisely because parties have to engage in the kind of communicable and simplifying discourse that can attract large numbers of voters. Occasionally political philosophers such as Mill have become members of parliament, but in that capacity their influence has not been notable. In the following chapters we will mention institutionalized liberalism only occasionally. It is an absorbing subject on its own, but it will not lead us to liberalism’s heart.

2.

Signing the United Nations Charter at a ceremony held in San Francisco on 26 June 1945.

Beyond the specifically political hues of liberalism, it has exercised a broader influence on thinking about, and in, the world. It would be no exaggeration to claim that the cultural features of political modernity—openness, reflectiveness, critical distance, scepticism, and experimentation—have taken their inspiration from a liberal mindset. An ideology’s impact cannot be measured solely on a narrow political platform.

There is something very unusual regarding the way the history of political thought is usually written about and taught. It is presented as the accumulated thinking of some fifty individuals, give or take. The express route begins around Plato and Aristotle, moving through St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, stopping at Machiavelli and then on to Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. From there it branches to Hegel, Marx, and Mill, and after that offers a series of lesser tracks into the 20th century. Occasionally there are smaller halts on the way that vary from journey to journey. We will not ignore that tradition, and

Chapter 5

is devoted to assessing some of its central liberal players. Indeed, at times strenuous efforts are made to broaden that canon, as in the Cambridge University Press blue books series, so we now have perhaps a hundred or so individuals who have to be taken into account. But think about the following for a moment: could any other branch of history get away with a narrative encompassing so few people, whether fifty or a hundred? Could social or cultural historians pull that off, for example? The reason for the strange historical sweep—or lack of it—of the study of political thought is complex. For one, it was not designed by historians but in the main by scholar-philosophers whose prime interest was in the unique, the outstanding, and the visionary. Second, it was rooted in now-disputed theories of evolution and progress that regarded political thinking as unfolding in a clear sequence. Third, it became a self-perpetuating convention, encouraged in universities, of addressing political ideas as reified and constituting the challenging heart of dignified culture, albeit with a striking Western bias.

Liberals of course colluded in that feat of human imagination, selective and elitist as it was. As suggested in

Chapter 1

, one way of approaching liberalism is to see it as a story about how individuals and societies change for the better over time. The tale liberals want to tell is about the growth of civilization and the progress of humanity. According to that optimistic narrative, human beings are increasingly driven by a love of freedom and opposition to tyranny and oppression. The cultivation of one’s individuality, and a respect for the individuality of others, are held to be the hallmarks of a decent society. Consequently liberals wish to manage the relationships between individuals, states, and societies by endowing people with sets of rights intended to protect and enhance their liberty and individuality.

The prehistory of liberalism

Where does the liberal story begin? The history of the word ‘liberalism’ and its usages is more recent than the ancestry of many of the ideas from which liberalism has drawn and subsequently embraced. The use of the word ‘liberal’ in a political sense dates from Spain in the second decade of the 19th century. In Britain that political sense can be found a few years later in the 1820s, as the word began to mean more than ‘generous’ or ‘ample’ and assumed the connotations of ‘radical’, ‘progressive’, or ‘reformist’. But the antecedents of liberalism are much older. We can find proto-liberalisms, or segments of what was to mature into a full liberal credo, from the end of the Middle Ages onwards.

Liberalism began, broadly speaking, as a movement to release people from the social and political shackles that constrained and frequently exploited them. Tyrannical monarchs, feudal hierarchies and privileges, and heavy-handed religious practices combined to create a sense of oppressiveness that became increasingly difficult to bear, and that steadily fell out of step with the advent of the modern world. The rise of liberal ideas is therefore linked to great social changes that were occurring across Europe. One of them was the challenge to religious monopolies, as secular powers sought to escape the control of the Church. It was followed by objections to the uniformity of religious belief and practice from within the domain of religion itself, typically during the Protestant Reformation. More generally, the right to resist tyranny was becoming an increasingly vocal demand, and it culminated in the celebrated insistence of John Locke on the right of the people to dismiss those rulers who heaped on their subjects ‘a train of abuses’. But the implied consent was still embryonic. It was not broadly democratic in nature except in the setting up of a political society—a fairly rare event. It centred on the voicing of dissent, not consent. The right of the people to say ‘no’ to bad government preceded by a considerable margin their right to say ‘yes’: to fashion desired political practice by mandating governments to act. And Locke recognized tacit ‘consent’ as a sufficient indication of the legitimacy of a government: silence was over-optimistically interpreted as political consent merely through a person using public goods such as a highway, or renting property in a government’s domain.

No less significant was the assertion of Locke and other 17th century thinkers that human beings were born with natural rights. Both of those concepts—‘natural’ and ‘rights’—were decisive to the future path of liberalism. For human beings now began to be valued as separate individuals, seen to possess innate attributes—in particular the capacity for life, liberty, and the creation and ownership of property—whose removal would profoundly dehumanize them. Enshrining those capacities through rights carried a vital message. It signalled the priority of those three attributes over other human features, for they were deemed to precede the formation of societies. It entitled people, once societies came into being, to special protection in the form of a contract between government and governed. Finally, attaching the qualifier ‘natural’ to that of rights implied that they were not a gift at the behest of rulers, or a precarious agreement between privileged individuals, or a convention that was kept up simply for tradition’s sake and was stuck in a rut. Rather, natural rights were simply

there

as an absolutely essential element of the human condition: people were born with rights in the same way that they were born with noses. The theory of natural rights eventually underwent some modification—the American Declaration of Independence notably substitutes the pursuit of happiness for the right to property—but it lasted as an anchoring point of liberal discourse until well into the 19th century, as a powerful statement that established limits to interference in individual lives. By the end of that century, although rights discourse remained central to liberal languages, most liberals no longer thought of rights as independent of their social origins and of social recognition. If the term ‘natural’ continued to be used, it was mainly by philosophers who employed it as synonymous with ‘self-evident’ or ‘intuitive’—concepts that in their turn possess the rhetorical power to remove something from dispute, as had previously been the case with the term ‘natural’.